Garbage Friends

Last week my uncle Claudio, my dad, and I, rented a little pedal boat and pedaled our way out at sea, a long way past the red buoy at the edge of the safety zone. They kept pedaling, and talking, and pedaling, and smoking, until dusk began to flame in the horizon. There was no land in sight — only water, perfectly still and flat, as though all along we’d been skating on a plain of blue and yellow glass.

“A quick swim and then we have to get back to the shore,” said my dad. I took off my shirt and jumped in the water. It was almost lukewarm. I wanted to impress Claudio, who used to be a professional swimmer and had made it into the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. He didn’t get past the qualifying rounds, though. When he talked about it he would allude, invariably and without any subtlety, to the night he had spent with the Swedish women’s shot put champion, on the eve of the race. The following morning she won gold, but he, exhausted, placed second to last. “No regrets!”, was his punchline to the story.

Stroke after stroke I gained more distance from the boat, until all their calling me back was but a feeble, faraway sound. Then, to drown out even the slightest noise, I plunged underwater and dove towards the bottom. I ventured deeper and deeper, until I felt my eardrums could take no more pressure, or else they would burst.

I don’t know how long I stayed down there. I can hold my breath for a really long time — minutes, hours, even days sometimes. But it was hard to tell how much time had elapsed. By the time I came back to the surface, my fingertips were shriveled, and I was cold. Night had fallen, the sea was rough and dark and the waves plunged me back down. I began to swallow water and couldn’t keep myself afloat. But just as I was resigned to drowning, something swept me up, and against my skin I felt the viscous, twitching presence of a thousand bodies. After an hour of being dragged along in this way, we were lifted out of the water and dropped onto a cold, hard floor. I lost consciousness.

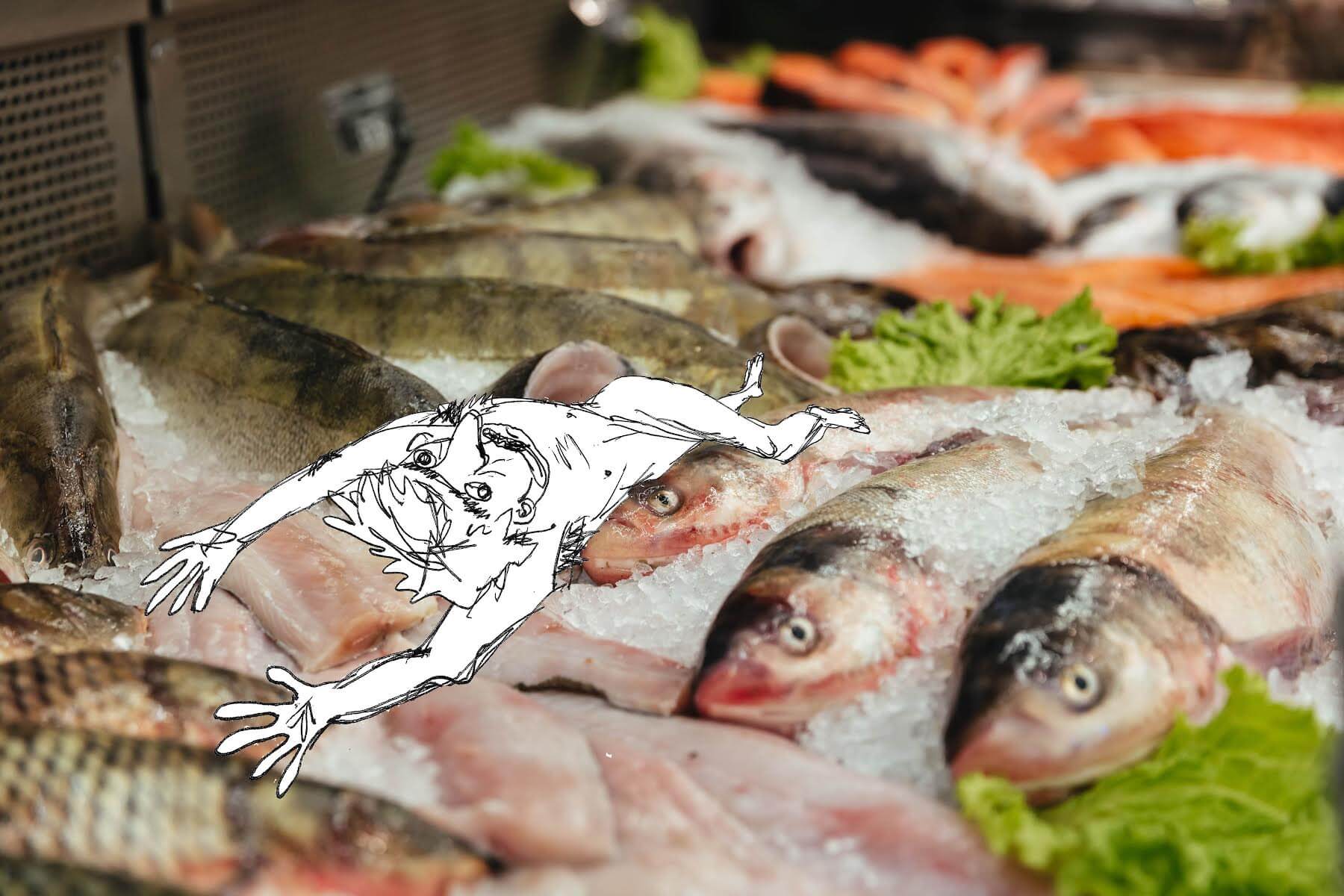

I woke up to the sound of human voices. It was dawn. A man pointed his club at me and said to another one, standing behind him: “Uaglio’, gard’ accà che pesce che t’agg’ acchiappato! Chisto al mercato vale nu milione!” Which is Neapolitan dialect for: “Buddy, look here, what a fish we fished. They will give us a million for it at the market.”

Beneath me, on a net spread out onto the floor, lay a restless heap of fish, each writhing and slapping life out of itself on the ship’s deck. I couldn’t speak. My mouth was dry from saltwater and my lips were bleeding from rubbing against the scales of fish pressed against me in the net. I tried to get up, but instead I just tumbled down from the pile and fell at the fisherman’s feet. He raised his wooden club high in the air. I looked up, and he swung the club down against my head. I lost consciousness again.

When I woke up, my body ached too much for me to move in any way, but I felt no need to. I was immersed in ice. Lemons and parsley were strewn about my head. Next to me they had placed an octopus and, further down, an array of gleaming sea breams and other small fish. I realized we were inside a display cart: above our head was a glass case to keep flies away, or to keep children from poking our eyes.

A waiter would come and wheel us around the restaurant, stopping at each table to explain the menu and let the customers pick their meal. This went on for a while, until I recognized one of the couples in the restaurant. His chest hair peeked out of his indecently unbuttoned blue and white striped shirt. She wore pearl earrings, and her silver necklace with the coral pendant. They were sitting in the corner, a candle flame flickering between them, and I had never seen them look so young and so happy.

Then someone must have ordered me, because the waiter came and brought me into the kitchen, where they laid me onto a large marble counter.

“How do they want it?” asked the chef, feeling my belly with his enormous fingers.

“Al sale,” replied the waiter. That’s when you cover the fish in salt — thick grains of salt that melt into one another in the big restaurant oven. Once the salt has formed a unified crust around the fish, they whack it open with a dull knife, like a plaster cast around one’s forearm. The salt shell breaks and reveals the fish: it has steamed off of its own juices inside the crust, and the liquefied salt has seeped into it. I don’t know if you have ever been buried in salt. It’s very unpleasant, and it makes you really thirsty, and still to this day I am always very thirsty.

Anyway, after the chef had sliced up my belly and took out all the things you don’t want to eat or even see — the heart, the intestines, and so forth — he went on to cover me in salt, and from that point on I couldn’t see much. All I could feel was the unbearable heat of the oven. Jesus Christ. You know what that’s like. Then, once I was cooked, they put me on a tray and brought me out to a table. The waiter whacked the salt crust open and there they were, mom and dad, smiling.

“This looks delicious,” said my dad. “I’ll clean it myself, if you don’t mind,” he told the waiter.

After peeling my skin off with a knife, he separated my flesh from my bones and forked a piece of my thigh. He blew on it to let the heat steam off, then brought it to his mouth. While he chewed me, my mom took a lemon and squeezed it over me.

“Wait,” she said. She poured herself and my dad some wine, and their glasses clinked in a toast.

In the end, they couldn’t finish me, so they took me to go. That way I made it back home. After three days in the fridge, nobody had touched me, or what was left of me. I must have begun to smell, because on the morning of the fourth day my mom threw me out in the garbage. And here we are. In this darkness. Covered in spoiled milk and orange peels. Ah! I have a feeling we’ll be friends, rabbit head.

A Year in Review

In alphabetical order, this year I became convinced I had: amnesia; ataxia; bile reflux; cancer; dysmorphia; tick-borne encephalitis; glaucoma; herpes (both kinds); ichthyosis; jaundice (which I did have as a newborn child, and had to spend the first week of my life inside an incubator, blindfolded and bathed in blue light); labyrinthitis; legionnaire's disease; lupus; Lyme disease; mad cow (variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob); meningitis; monkeypox; mycoplasma; nephritis; prostatitis; rickettsialpox; salmonella; sepsis; tapeworm; tinnitus; and zika virus. Other things I was able to rule out through a simple Google search.

Each time, one or a handful of signs would send me in a spiral of fear and sometimes despair. And each time it got worse because, I would think, last time the signs were a false alarm, but what are the chances they might turn out to be a false alarm again? The probability of discovering plausible symptoms and them amounting once again to nothing got lower and lower after each scare. Ok, I don’t have monkeypox, and I didn’t have amnesia, and I didn’t have a jaundice relapse, but what are the chances that I am once again deceived, and I don’t have cancer? How can the universe, so to speak, send me all these indications, without at least one of them pointing to a reality? As a result of this thinking, the year was spent in great confusion.

Amnesia was in January, after I couldn’t remember a single thing I had done on new years’ eve. “You blacked out from drinking,” said my former friend Antonio — but I also had a bruise on my forehead. That could mean permanent brain damage. On the same day, an odd-looking blister on my arm procured me two hours of dismay, until I recalled how I had burned myself trying to light a cigarette on the stove on new years’ eve. “See, you do remember something after all,” was Antonio’s comment.

The rest of January saw mostly minor scares. Then in February I thought I had rickettsialpox, which is caused by one of the smallest known bacteria in the world. I immediately called Lotte, my girlfriend at the time. She said she wasn’t too worried. She reminded me how two years prior I’d grown convinced I had syphilis, despite having no symptoms. I told her I should have never told her that story, and that the way she told it now was a misrepresentation of the facts. I told her everybody knows syphilis is the Great Imitator, meaning it can show up in all sorts of deceptive ways. You might think you have a stomach ache, and instead it’s the first pangs of syphilis. She sighed. I told her rickettsia is one of the smallest known bacteria in the world. I told her rickettsialpox had been first discovered in an apartment complex in New York, in the ‘50s. “Right here in Queens, in fact,” I said. It was as though I could hear her shrug over the phone. She said the symptoms I had described to her sounded completely imaginary, and that I had too little faith in the influence our brain (or spirit) can exert on our body, for good or, in my case, for worse. She said I should try journaling, to put my fears down on paper and face them with detachment. She said meditation, too, would help. I told her yes, that I believe in the influence our brain (or spirit) can exert on our body, but I also believe in bacteria. I told her that not everything is in our control and that it would be arrogant to assume it is. You don’t heal a broken bone with meditation. You wouldn’t try to journal an earthquake away. Why should it work that way with microbes? They’re as real as a car running a red light, I said, as real as someone holding you at gunpoint — just invisible.

In the end I didn’t have anything, which doesn’t mean she was right. But something broke during that conversation. She thought I was going crazy, and I thought she was being foolish. And aside from that, sex was no longer so appealing. In April we split up. In May I tested negative for diabetes, and an ultrasound determined I did not have kidney stones, testicular tumors, or any inflammation of the prostate. “And you’re not pregnant, sir,” put in the doctor with a smile, revealing all his lack of professionalism (which I already suspected) and effectively invalidating the results of the tests he had performed. One week later, I had the same examination done by Dr. Stratos, a heavy Greek man in his seventies who hardly spoke and who, instead of breathing, merely sighed. Perhaps he had asthma. Hopefully nothing contagious. He confirmed the results.

In June I thought I had a tapeworm in my bowels. And again I had my motives. All of a sudden I was hungry all the time. Despite that, I started losing weight (almost two pounds). And then I remembered how in April I had eaten in a hotpot restaurant with Lotte. It was the night we decided to end things. Although I couldn’t remember what we ordered, it was likely we had pork and that I hadn't cooked it long enough inside the broth. I texted her asking if she still had the receipt from the restaurant, but she never replied.

Tapeworms temporarily live and lay their eggs in pigs, as they wait to settle inside their final host — humans. I explained this to Fabio, my roommate at the time, but he’d laugh and tell me I should just eat more. He said that way I’d kill two birds with one stone: I wouldn’t be hungry anymore, and I wouldn’t lose weight. He was right, but I had my reasons for not finding his words reassuring. He was the type who could have caught the bubonic plague and mistaken it for acne. The careless type. So, for about a month, before falling asleep, I would lay awake in the dark and wait. I tried to keep completely still. I would listen to my body, quite literally. Those moments were tense — I felt like a cat in the jungle, perking up its ears to spot its prey. And I swear that on some nights I felt the tapeworm move inside me. Then my sleep would be ruined.

I forgot about the tapeworm in July because I thought I had lupus, or hepatitis, or perhaps diabetes once again. I felt exhausted, but now I see that it must have been all those sleepless nights lying in wait. In any case, I did all the tests and I was fine. In August I tested again for everything, and again in September. Which cost me a lot of money, but was worth it, for peace of mind. One morning in August, however, I woke up to find two red bumps on my forearm which I interpreted to be bed bug bites. So began a month of restless perlustration of every corner of my body, bed, and room. I washed and re-washed my clothes and linen; I scattered glue traps in strategic places around my bedroom; I bought diatomaceous earth and laid a small heap of it on my bedroom’s doorstep, along the walls, and in concentric circles around the perimeter of my bed, which I moved to the center of my room; I ordered a pheromone-releasing ‘vulcano’ trap online, as well as special plastic cups which I placed under the legs of my bed. I also posted several ambushes, lying once again awake at night, once again perfectly still, only to jump out of bed at three in the morning, flood the room with light, and furiously inspect the linen and the mattress. I found nothing, but promptly mistook it for hard evidence.

The fear of bed bugs was dispelled, though not entirely, towards the end of the month, once I paid an inspector to come check the place with his certified bedbug-detecting beagle. As I sat on the stoop smoking and awaiting their arrival, I sighted Matcha, the beagle, approaching from around the corner on the inspector’s leash. I waved at them somberly and cast a look of terror into Matcha’s eyes: the removal of my paralyzing doubts, and the possibility of going back to performing basic daily life tasks, depended on her. She looked up at me and wagged her tail.

Once in the house, we went into the kitchen, where I showed the inspector an assemblage of suspected bed bug traces, which, like a paleontologist presenting the fossils unearthed in his excavations, I had arranged on a glue trap on top of a stool. These were small, bug-sized or less-than-bug-sized pieces of unknown matter — possibly wood, food, or wall paint —, ranging from yellow to brown, which I had found during my expeditions in the meanders of my bedroom. Exhibit A was a crumb, exhibit B a cuticle, and so forth. He pointed his torchlight at the glue trap and examined the carefully laid out array of my findings for 1.5 seconds before dismissing it with a “Nope, nothing here.” Then began the inspection.

Once the inspector and the beagle left, I sighed with relief and sat heavily on the stool in the kitchen — the only walkable room in the house, since, in order to let the beagle thoroughly sniff out the apartment, I had moved all the house’s furniture a few feet away from the walls. The result looked like a picture of my own state of mind. Night was falling, and the shadows of the furniture I had amassed along the corridor stood in half-darkness like totems to my madness. When I got up to put all the drawers, the bookshelves and the desks back in place, I realized I had been sitting on the glue trap I had prepared for the inspector. It was stuck to my ass: I had been the bed bug all along, and had finally caught myself.

In September I moved out of the apartment and into my current house — not quite yet a home. I couldn’t deal with Fabio any longer. Our lifestyles didn’t match, down to the smallest detail. To give you a sense: say I’d been drinking water from a glass — I always drank from the same glass — and left it on the counter for five minutes while I washed my hands in the bathroom. He’d walk into the kitchen and simply drink from it, as though it were his glass. And then he’d put it back right where I had left it, without cleaning it or even rinsing it, so that if I wasn’t careful, I would drink from it again. Needless to say, knowing his lifestyle, this was a huge risk.

October and November went by smoothly, save for a few moments of panic here and there (liver cancer; meningitis; malaria), which I was able to manage. The apartment is almost empty and in truth it looks more like a monk's cell, or perhaps a psychiatric ward. It makes me self conscious about bringing girls home, which is ultimately a good thing, given all the things that one can catch, even with precautions. Besides, I haven’t been going out as much. The city is lonely, but not in the charming way people imagine. I never had many friends, and my family is far away. Work used to fill up my schedule. Now, since I had to quit my job a few weeks ago (a colleague of mine had scabies, I’m certain, though she claimed it was eczema), I have a lot of time to myself. I try to put it to good use and have been reading on the internet and learning very much.

In the middle of December, however, something completely new happened, which at first I found terrifying. I didn’t dare tell anyone, and I could find no answers online. So I just watched it unfold. First my penis — excuse me but my dick, it got longer, yet not in a way that anyone would find desirable. Day after day, it grew several inches, but also became thinner, until after a week it was but a long, limp string. Peeing became very difficult and messy. Then, on the seventh day, I woke up and found it had fallen off. In its place nothing: just flat, freshly formed skin. I could not pee, but I did not need to, nor was I thirsty. How can I explain that, looking at the smooth patch of skin that was now my crotch, I felt a strange relief? In a way, this meant one less thing to worry about.

Shortly after, my tongue retreated in my throat, almost occluding it; then my gums rose until they enveloped my teeth. Finally I could not part my lips anymore. They’d merged together, sealing my mouth shut: now there is no trace of it. But I am not hungry. My nostrils, too, closed overnight, and my nose began to sink into my face until not even a small bump or dent was left. Thankfully, I do not feel the need to breathe. My eyes, instead, simply fell out, painlessly, and the skin in the empty sockets quickly healed. The ears at first swelled and stretched into elephantine proportions, but then they too fell to the ground with a kind of rubbery thud, like theater props in a grotesque play. A layer of skin grew over the holes that were left. Sounds still come through, but very muffled.

Today, the thirty first of December, my body felt lighter than usual, at least from the neck down. It felt dry and lifeless, and, how can I say, useless? I was dragging myself blindly across the floor — in the large, empty living room, I think — when finally I felt my head fall off. Or rather, I felt that the head remained, that I was still in it, but that the rest of the body had come off — it had been shed, so to speak. I immediately felt better, as though a weight had been lifted off my chest, had I still had one. My preoccupations vanished: no more organs subject to decay, no more bowels breeding armies of bacteria, no more senses to smell, taste, touch, or see the signs of illness, no more orifices welcoming in all kinds of viruses and diseases. Just a deep loneliness, a deep darkness, without any distraction. I have never felt so present to myself. Being alone inside my head means I’m free to roam it.

This happened in the morning. And just as I was rejoicing at the newfound peace, I heard the doorbell ring. I wasn’t sure at first, but then it rang again, and again, a sound that seemed to come from a mile away. I thought they’d just give up, but then I heard her voice, and realized I’d left the door unlocked. Lotte had let herself in. At first she let out a scream. She asked what the hell I was doing on the floor. She said she thought I was dead. I said nothing of course since I no longer had a mouth. She explained that my family had reached out to her and asked her to check in on me, since I’d stopped picking up their calls. That’s why she was there, she said. Then she served up more or less the same repertoire she’d always used on me: that I needed help, that I couldn’t let my life be eaten up by fear, that mine was a mental problem, and there were people who could cure it. After an hour of this kind of talk, now and then broken up by her sobs, she wished me a happy new year, and left. “Happy new year,” I heard myself say out loud, though I cannot explain how.

Now it’s past midnight. I know because I can hear the fireworks crackling and booming in the sky. People celebrating the new year. What can I say? Things could be worse. Those could be bombs out there, for all I know. Because the fact is that the world is full of things that try to harm you, big and small. Things, people. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. Don’t let anybody tell you otherwise.

Then it came that the king had a strange dream…

And he woke up, gasping. His room was occupied by twelve peasants, armed with pitchforks and sickles.

“Where is the queen?”, he shouted, throwing the sheets in the air and jolting up to stand on the bed, his face red with terror and rage. In his dream he had finally married, and was now infuriated that someone should have taken his spouse away.

Instead of responding to his question, a man of barely twenty five — the youngest among the peasants — stood forth and rolled out a yellowed parchment. Having introduced himself as Jonathan Pipe, emissary of the people, he began to proclaim the verdict the rebels had crafted in order to put an end to the king’s tyranny. It was a very long verdict, written in the smallest handwriting, in order to fit it on the only decent scroll they had managed to procure.

Mr. Pipe’s eyesight happened to be very poor. His family could barely afford to buy back their barley and rye from the country squire — let alone spending money to buy candles—, and Jonathan, being the only literate person in the village and one of few in the whole province, was constantly asked to redact letters and perform all sorts of calculations regarding this or that farmer’s harvest, all in the dimness of the cold, damp room he shared with his brothers and cousins, and, what’s more, after a long day spent toiling on the fields. From the way he squinted over the verdict’s small, blotchy tracks of ink, one may have guessed that he was in fact very close to becoming entirely blind.

In truth, Mr. Pipe, emissary of the people, could hardly read in the first place. Although he was considered literate — even an intellectual of sorts — by his neighbors, his education had consisted of less than two years of schooling some thirteen years earlier, when the village priest, having heard of the young boy’s frequent religious trances, and having noticed in him a more docile nature than that of the other townsfolk, whom he regarded as intractable pagans, had agreed to take him in as an altar boy, providing him with a few basic notions of grammar and spelling. But before the end of the second year, Jonathan’s parents had called him back on the farm. His older brother had died of pneumonia and they needed another pair of working hands.

Having spent most of his life in solitude or surrounded by folks whom he felt he had the right to consider somewhat inferior, Mr. Pipe now felt a scorching sense of self-awareness. Not only was this the largest audience to ever hear him read, but it also included the most illustrious and best educated listener he’d ever had: the king himself. Before he finished reading the first paragraph, half an hour had elapsed. Drops of sweat streamed down his temples, tracing wet trails over his flushed, burning cheeks. At times, a drop of sweat would fall from his brow directly on the parchment, blurring the text even further. Mr. Pipe did not need to raise his eyes to picture the proud, scornful simper on the king’s lips. The embarrassment made him stutter, which, in turn, caused the reading to proceed at an even slower pace.

“The hell with this,” burst out one of the peasants, “let’s just chop his head off!”. For the verdict was death, to be carried out by means of beheading. The others clapped and were already rushing towards the bed when Mr. Pipe, seeing the chance to redeem his near-illiteracy by demonstrating, at least, his moral stature, raised his hand towards the sky and, without turning, shouted:

“Hold it!”— here he paused and prepared to enunciate the rest with utmost solemnity — “Do not touch the king until he has heard everything the people have to say to him”.

Rolling their eyes, grunting, and cursing, the peasants took a step back and allowed him to continue. Encouraged by their obedience and by the authority he had displayed before the king, Mr. Pipe went on to deliver the rest of the proclamation.

The reading required several hours. On certain words, or even entire lines, the ink had blurred into an illegible splotch. As he drew the parchment closer to his tired eyes, Mr. Pipe feared the delay would come off as further proof of his ineptitude, whereas, really, nobody could have deciphered such meaningless black blots. Now a throbbing headache made him dizzy. His legs trembled, his knees deserted him.

After the fifth hour, Mr. Pipe, emissary of the people, started falling back into one of his religious trances. It seems he was something of an epileptic, although the surviving accounts are not clear on this point. What does seem almost certain, however, is that the trances, which apocryphal hagiographies have passed on as ecstasies caused by divine inspiration, were not so religious after all. Some claim that, on the contrary, they were merely the nervous crises of a young man whose sexual development and curiosity had found no outlet or relief during adolescence. Instead of six-winged seraphim twirling above his head, Mr. Pipe’s mind conjured his cousin’s soft, naked breasts, which he had so often seen, each year with a different newborn child grasping and sucking at the nipple. The fact that, during these trances, as he drooled and stared into the void, Mr. Pipe would often grope the air in front of him, gave credence to this theory.

Others still — those who see in Mr. Pipe neither a religious saint nor some slobbery lecher, but rather one of those champions of the peasant world that history with a capital H so rarely admits in its records —, insist that actually, on such occasions, Mr. Pipe’s mind traveled back to the memory of a walk through the meadows, at dusk (the very meadows an enclosure act would soon deprive his people access to); or else to a bright summer morning, when he and his brothers bathed naked in the cold waters of a torrent (the very torrent a local nobleman had recently rerouted away from Mr. Pipe’s village, and which, today, serves as a drainage canal for a nearby pharmaceutical plant).

In order to snap him out of such trancelike states, one of the peasants would prick Mr. Pipe’s buttocks with the prong of his pitchfork — lightly, at first, then with increasing force as the hours passed, tearing off large patches from his trousers. Jolted back to the present, Mr. Pipe would immediately delve back into reading the proclamation with great ardor, but would soon get distracted again, and fall back into his reveries.

Evening was approaching. The king, in the meantime, had rescued the bedsheets from the far edge of the bed and had tucked himself under them, to hear the rest of his death sentence with greater comfort.

“...Signed, The People,” Mr. Pipe finally concluded. He lowered his trembling arms and took a long, deep breath.

A few instants passed in complete silence before the door came down with a loud thump. A small platoon broke into the room, brandishing swords and spears and a shield bearing the royal emblem. Before any of the exhausted peasants could react, they were disarmed, handcuffed and escorted out.

Since morning, the army had been fighting off the rebels in the surroundings of the royal palace, eventually regaining access to the king’s residence. The servants, who now came out of hiding, had informed them of the situation.

“They’ve been in there all day,” the cook had said with a shrug. Quietly and slowly, almost tiptoeing, lest the rebels should hear the clanging of their heavy iron armors, the royal guard had made their way across the palace’s frescoed halls and had reached the king’s bedroom.

The twelve peasants were brought out onto the courtyard and immediately beheaded. Their headless bodies and bodiless heads were piled up on three carts, each pulled by a horse, each horse unaware of the historical significance of the day’s events. The soldiers spurred the beasts and trotted away into the darkness, eager to dump the corpses in a nearby swamp and finally go to sleep. Legend has it that one of them, having heard the rumors about Mr. Pipe’s mystical visions and smelling sanctity in the whole affair, secretly shucked Mr. Pipe’s eyes out from the severed head, pocketed them, and sold them to the only Catholic church in the country, where they were venerated for centuries by a small but resilient community of devotees.

The commander of the royal guard, meanwhile, informed the king about the executions.

“Good,” said the king. “Now leave me alone. It was a long day and I am tired. I shall get some sleep.”

The captain clacked his heel on the floorboards in stately salute, and left the room. The king embraced the pillow with both arms. He brushed his cheek against the lining until he found the right spot. Before one minute had passed, he was asleep.