Text by Joshua Craze. Photography by Wolf Böwig.

2024. Nairobi, Kenya

Dear Wolf,

You sent me four images for my trip, and I thought of them like charms, meant to keep me safe. I was to go to Juba and then head to the South Sudanese border with Darfur, before plunging into the war that raged to the north. On the plane from Nairobi to South Sudan’s capital, I kept staring at your images on my laptop screen, as if I were a detective investigating a crime scene. There were two collages and two photographic polyptychs. What hidden logic led you to send me these pictures, and not others? I closed my laptop before the plane banked down over the Nile with the internal relationship between the images still mysterious to me.

I arrived in Juba on Valentine’s Day, to be greeted by a public letter from a leading South Sudanese politician, accusing me of being in the pay of a rebel leader. As a precaution, I spent the night at my hotel, and looked, once again, at your images, which transported me through time. I suddenly remembered the sadness of a demobilized Mende militia fighter sitting disconsolately in his carpentry workshop, surrounded by garbage. Soon, other memories emerged. Of scholars trapped in the binary brutality of the war on terror. Of sorcery and spells, proven and alleged. Of violence, abstract, and all too concrete.

The next day, the poisoned letter was followed by a front-page denunciation in a newspaper run by the National Security Service. Then the surveillance started. I had to cut my trip short and never got to Darfur, but I travelled nonetheless. Sat in my hotel room, I tried to work out the plot against me. Was there a real threat? How far up did this go? Was I simply being paranoid? Lying awake at night, I mapped cartographies of potential violence: the checkpoints studding the city, the quickest route to the border, the desolate stretches of road on the way there. By 4am, I needed to get out of my head, and so looked once again at what you had sent me. Through your images, I went to other borders and other times. Your pictures helped me make a different sort of map. An escape route.

2003. Bo, Sierra Leone

There was such a thick layer of dust on the workbenches that it felt like I was looking at a blurry photograph. At first, I thought it was sawdust, simply the mark of a successful business, but I soon realised I was looking at the symptom of an underlying disorder. Coke cans had crept under the benches and taken up residence. Plastic bags, emptied of gin, decorated the floor. Even for a workshop, even in rural Bo, this was an unusual amount of disorder.

A week earlier I had been in Freetown, Sierra Leone’s capital, and had marvelled at the social precision of my friends’ decorative choices. In the small homes of Freetown’s Krio bureaucrats, mantlepieces bore the weight of whole family trees, snapshot at graduations and marriages, while walls charted carefully-plotted class aspirations—degree certificates and the portraits of esteemed relatives—all perfectly clean and correct.

It was harder to see the signs in the carpentry workshop. One, I noticed. There was a small scar on his upper arm. The memory of an incision. This was where the doctor placed the herbs that had saved him, time and again. The former militia member sat tall on the workbench and spoke.

They had attacked the Kangari Hills at dawn. The white man crouched next to him had urged him forward and when he ran the bullets erupted. As he described running towards the hills, he abruptly leapt from his chair and started running on the spot, his hands holding the empty air as if it were a rifle. That’s when the herbs had saved him. Everything that saves becomes a curse.

The war ended. The fighters were, as the technical saying goes: Demobilized, Disarmed, and Reintegrated (DDR). He was given training in carpentry and a position at the workshop. That was the formal process. But none of the foreigners involved in DDR gave a thought to his herbs. To become bulletproof, the Mende Karamajor militia fighters had been blessed. With blessings, came injunctions. You cannot cook. You cannot clean. (A picture of the patriarchy). You cannot be killed by gunfire, but you cannot take care of yourself. He got up from his seat again and mimed sweeping the floor, an invisible brush in his hands. The Coke cans failed to be moved. The Mende customary authorities had organized a ritual lifting of the prohibitions, called “Now Everything is Over,” but they charged money for participation, and he could not afford to pay. DDR didn’t extend to rituals.

“At least,” I joked, “no one can shoot you.”

He looked at me gravely.

“The war is over,” he said.

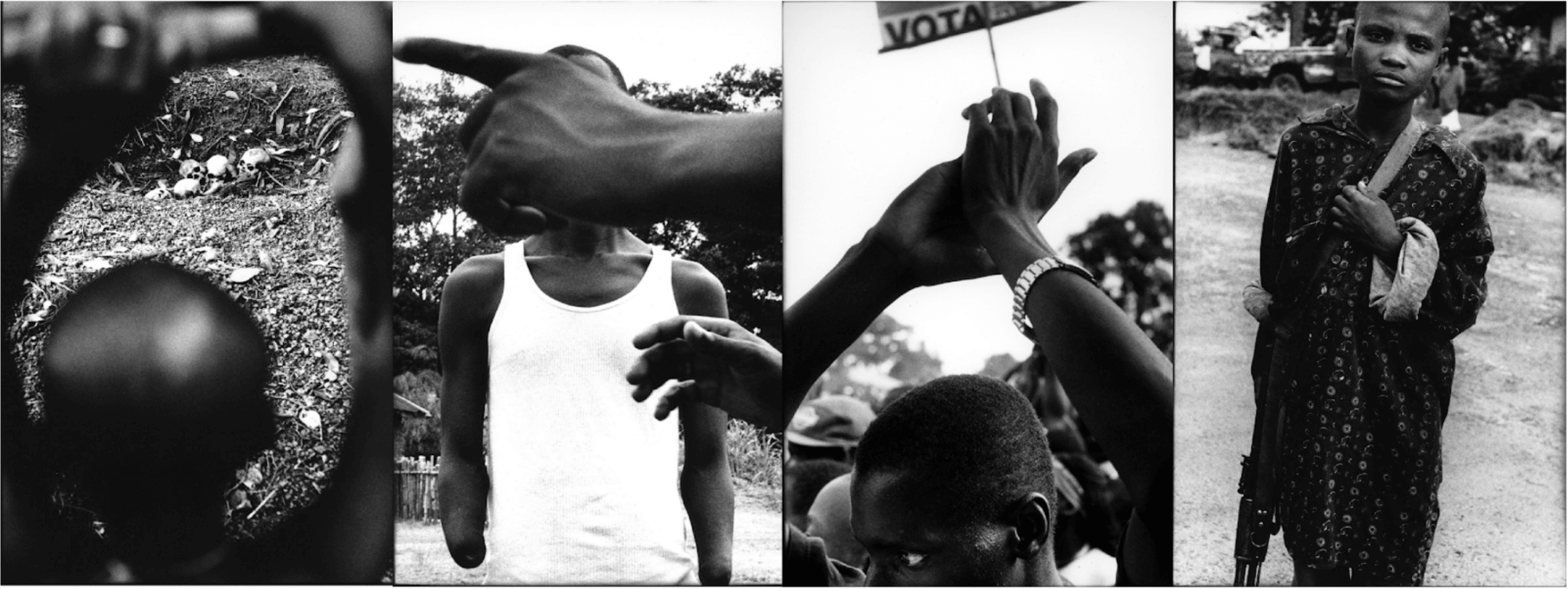

Wolf: It was your photographic polyptych from Sierra Leone, Guinea Bissau, and Liberia that took me back to Bo. In the first shot, in the top left corner of the panel, a boy’s hands are raised above his head, as if gripping the frame of a shack, and through them, we see four human skulls in a depression made in the earth. For a moment, I think the young boy is holding the skulls.

Looking at that image made me start to create a mental encyclopaedia of the gestures of war and the gestures war makes impossible. At the onset of the conflict in Sierra Leone, the rebels cut off hands—we see one potential victim of such mutilation in the second photograph in the polyptych. The western press called it brutal barbarism, but it was much worse than that. The absent hands signed a language as polyvalent as any other. The international donors had spread the slogan “one hand, one vote.” The mutilations said: go back to the donors and tell them there will be no election until the foreigners—the white South African mercenaries and the Nigerian peacekeepers—have left. Later, the rebels chopped off limbs to prevent farmers from collecting the harvest. Absent hands can sign so many things. Violence is not the opposite of speech.

In the second photograph, a pointing hand blocks the face of the mutilated man. It gestures outside the frame of the image. I think of the finger as pointing to the third photograph in the polyptych: a man’s hands are raised above his head, as if he is holding the sign that we can glimpse at the top of the image: “VOTA,” it reads (we must be in Guinea Bissau). When the war-story ends, the liberal playbook is rolled out. Elections. Progress. Democracy.

What then to make of the haunting portrait that ends the polyptych? It is the only image in the series in which someone looks directly at the viewer. After all these gestures, disconnected from faces, a young boy stares at us, still armed.

In 1972, Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin made a film called Letter to Jane. It’s a fifty minute essay that analyses a single photograph of Jane Fonda, taken in Hanoi. Jane is looking at the Vietnamese, and Jane is concerned. Her gestures and body language show her humanity, but, Godard and Gorin claim, not that of the Vietnamese. She is in the centre of the shot and what is at stake is not solidarity with the Viet Minh, but her own pity. Godard and Gorin trace Fonda’s positioning back through televisual history, all the way to the Renaissance. They uncover a fugitive figure, present throughout the story of the West: a picture of concern and care, in which those depicted as victims are rendered voiceless.

If he were still alive, Godard could update his film, except now his focus would be on Samantha Power, the head of USAID. I can see her sitting on the border with Chad, really listening to Sudanese refugees. All the images I look at are of HER LISTENING, and her listening is so noisy that we cannot hear the voices of the exiles. Her listening is SO LOUD, she hopes, that it will drown out what is happening in Palestine. We could follow Godard and Gorin and trace a contemporary history of these self-satisfied scenes, in which violence is just the necessary backdrop for the white saviour’s arrival.

But all that feels pat to me. Your pictures, Wolf, offer me another route, a means of tracing the persistence of conflict long after war’s end. Through your images, I come to see the gestures that condense the war, and show that, while there might have been a peace agreement, the war continues, inside of us.

The hand pointing the handless man to an unseen future. The Karamajor militia fighter mimicking the act of brushing his workshop. The boy, staring. Survivors, unsaved.

2023. Nzara, South Sudan

I was in Western Equatoria, South Sudan. Other than the WFP warehouses, those enormous white canvas tents on the edge of Yambio, the state capital, these were the biggest buildings I had seen in the state. Enormous old factories made of red brick, the machinery inside stripped for parts, but still gleaming, improbably, over half a decade after the end of British imperialism. Once functional distilleries seemed to me then as mysterious as the ruins of an ancient civilisation. My tour guide, who was paid a pittance to pointlessly try and prevent any further thefts (there was nothing left to steal), proudly pointed out engines made in Sheffield as if I were in a museum in Derbyshire, surveying the history of British industrialism, which, I suppose, is exactly what I was doing.

On the way back to Yambio, I glimpsed the ruins of other futures. Broken waterpipes leading to nowhere, abandoned when the debt crisis of the 1980s led Nimeiri, then Sudan’s president, to give up on his hopes of developing the south. The landscape of Western Equatoria was littered with dishonoured promises and hollow dreams. Expensive Japanese mills, a legacy of the bright hopes of South Sudanese independence, rusted next to planes that had fallen from the sky and found new roles as playgrounds.

None of that matters now. South Sudan is a world full of holes. We drove past absences. The savannah that stood where proud teak forests once grew. The pits and depressions of the gold mines. All those precious materials have left the country, looted by South Sudan’s generals. The trees head to India and Dubai, and then return, via the magic tricks of capital, to be deposited into the pockets of the generals, who use them to buy property in Nairobi.

Broken dreams of development had left other, more spectral traces. A British Resettlement Order from 1922 forced the Azande people out of their scattered, customary forms of habitation, and into model villages along straight government roads. Fifteen years earlier, the British had killed the Zande king. Confusion reigned. Sorcery accusations spiralled. Bad things were being done to the Zande. Marriages fell apart. Who was at fault?

Witchcraft was a way of naming the confusion. While British officers could not be accused without fear of imprisonment, one could always blame a commoner for one’s troubles. The Azande turned on each other. It reminded me of Freetown, where accusations of poisoning were frequently made by an aspirant bourgeoisie who feared being tied down by their rural kinfolk. The middle class wanted to eat alone.

Witchcraft is not the opposite of modernity, but the marker of its broken promise. In Yambio, accusations were once again rampant. The economy had imploded. There were no jobs and no wages. Men complained that their wives acted as if possessed. These women make unreasonable financial demands, the men told me. The only thing to do, the men said, is to go to Juba and hustle for money. Young women responded that their men had abandoned them and gone to the capital, where they get lost in alcohol. Perhaps they’ve been bewitched by their girlfriends, their wives suggested. Just as during the British colonial period, such discontent never indicts those actually responsible for the catastrophe. Never name the generals.

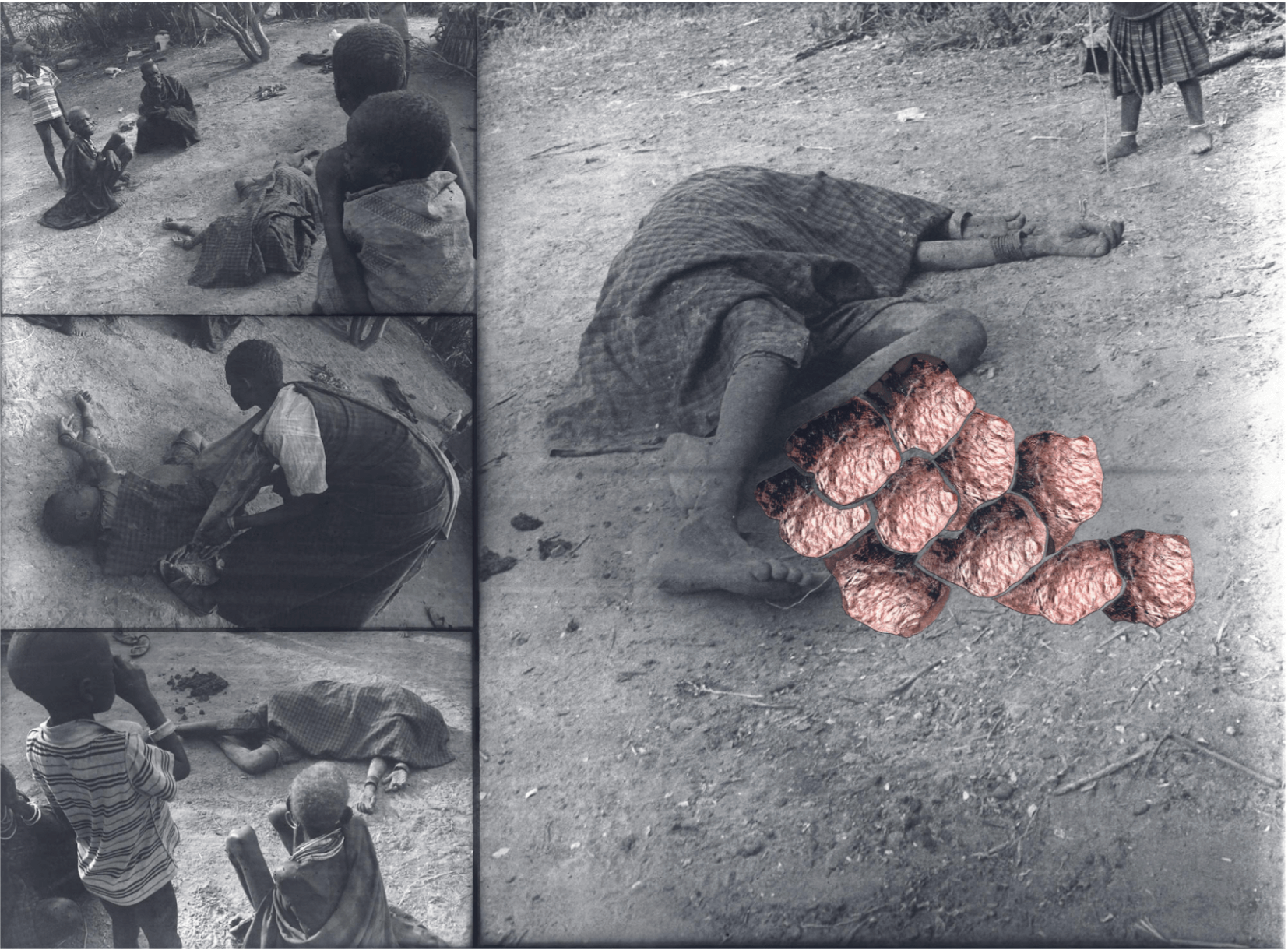

A witchcraft accusation is a crime scene. So, even more directly, is a poisoning. In your second polyptych, Wolf, there is a narrative, though the main event occurred before the photographer arrived on the scene. In the top left image, a body lies on the ground, a cloth draped over it. The caption tells me we are on the South Sudan-Uganda border. From the look of things we are in Eastern Equatoria. It is a poisoning, the caption says.

I said your images were a narrative, but that isn’t quite right. The polyptych stages four moments of spectatorship. In the first image, the compound’s residents behold the corpse, framed by the elephant-grass wall behind them. In the second, just to be sure of the situation, someone inspects the body. (The dead so rarely lie dead). The third image takes us across the compound, and we behold the corpse from the perspective of the child and the elderly woman we see in the first photograph. (The body still does not move). Finally, in the last and largest panel of the polyptych, we are offered the corpse without viewers, except now something monstrous has happened next to it.

The question I see circulating through your images, Wolf, is this: How to behold a corpse? What questions can we ask of the mute body before us? With every death, a narrative is interrupted. The first question of the spectator is always: What happened? Soon after, another question appears: Who is to blame?

How does one determine what is a poisoning (intentional and violent) and what is food poisoning? What is tragic contingence (disease, weariness) and what is a plot? Like the paranoiac and the witchdoctor, the person convinced that a relative has been poisoned has one mantra: nothing is accidental. Someone must be answerable for what has happened.

Poisoning and witchcraft are similar accusations; they both grab hold of those nearest. According to the mantra given above, the body covered by the blanket was neither killed by years of government abandonment nor murdered by food insecurity. The poisoner must be close. Abstract words don’t cut it. The poisoner must be someone with whom one is intimate enough to share food. Blame not what is out of one’s control. (A mantra shared by witchcraft accusers and self-help aficionados alike).

How to make sense of an upside-down world in which one has no hope of building a flourishing life? In which development has died and the country is being eaten alive from the inside by predatory politicians propped up by the international community?

You reach out to those closest to you. The bodies that warm the night. You think of those you love. I look at the strange pink brains that have been placed onto the fourth panel of the polyptych. They are utterly foreign to the rest of the images. These are the aliens that one must domesticate. Much later, long after I composed this essay, I learned that they were shards of your flesh.

Poisoning and witchcraft allow one to try and understand how the intimate are possessed by outside forces. How those you love come to hurt you. Such accusations place the blame on those closest, and let the generals—let us not mention the IMF—off the hook.

In this sense, poison and spells prove much more tangible, much less evanescent, than slippery, mysterious things like empty gold mines and absent teak forests.

2006. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Another country, another crime scene, this one rather more scholarly:

Kariakoo is a bustling area of Dar es Salaam, notable for the groups of men who stand indolently on the street, still as statues, before bursting into life whenever Chinese or Israeli traders walk past, their hands moving to hidden pockets and socks lined with their wares: the gem stones and gold that wash into Tanzania from around East and Central Africa.

Almost a decade ago, one November evening, I was at the wa Mtoro mosque, and salat al-magrib had just finished. The faithful poured out into the street. The small bookshop next to the mosque drew me in. I was feeling very peaceful. My friend had asked me to pray with him, and I had acceded to his request, despite my hesitations. I was glad to have done so. Standing in the shop, my hands still remembered performing wudu: my left arm washing the right, and then the reverse, one arm helping the other; my body remembered bowing low, my eyes aware that we are all performing sujood in unison.

At the back of the shop, lining the shelves above the bookseller, were stern rows of hardbacks: Qurans, commentaries by Ibn Kathir, and a few works by Ibn Taymiyya. Ornate Arabic etched in gold ran along spines that were freshly dusted that morning. These were books for distinguished customers.

In front of the bookseller, piled in cardboard boxes, were pamphlets written in Swahili, with titles like Majadiliano kati ya Mkristo na MuIslamu (Debate between a Christian and a Muslim). I idly flicked through the pamphlets (the Muslim wins) before my hands stopped on something out-of-place. The crime scene:

It was a large book. 398 pages. Written in Swahili. (The only book of such a length, written in Tanzania’s national language, that I ever saw in an Islamic bookshop in Dar es Salaam). My surprise grew when I examined the work. It was volume thirty of Sayyid Qutb’s commentary on the Quran, Katika chivuli cha Quran (In the Shade of the Quran or في ظلال القرآن).

Qutb wrote his treatise in prison. Gamal Abdel Nasser took power in a coup in 1952, overthrowing King Faruq. Initially, Qutb, a young Islamist poet and scholar, saw the coup as a step towards Islamic unity. The bodies of the Arab states, he hoped, would begin to move as one. In a series of radio broadcasts, Qutb heralded Nasser. He became known as the tribune of the revolution, in homage to Mirabeau. This arrangement didn’t last long. After the Muslim Brotherhood opposed the Anglo-Egyptian pact of ’54, the Brotherhood’s newspaper—of which Qutb was the editor—was shut down, and soon enough he was arrested. He would spend the rest of his life in and out of jail, increasingly physically sick and disgusted by the jahaliyya (ignorance) of contemporary Egypt. The Egyptians, he held, prayed like Muslims, went to the mosque like Muslims, but at their core, they didn’t practice their faith. The situation was just the same as in Arabia, prior to Islam. We must, Qutb thought, begin again and truly practice our faith.

For Qutb’s acolytes, Islam in Tanzania remained in the hands of the sheikhs and the madrassas, who preached religion, but practiced jahaliyya. I wanted to meet Qutb’s translators. After some discrete inquiries, I tracked one of them down, and he agreed to talk to me at a Somali hotel that I would later learn housed the ’98 bombers of the American embassy. The translator failed to show. In the restaurant underneath the hotel, a man pushed me up against a wall and told me if I came back I would be killed.

The next day, I returned to the restaurant, and made it as far as the counter. I didn’t get to eat the bariis I ordered. It would take weeks to earn the trust of the translators.

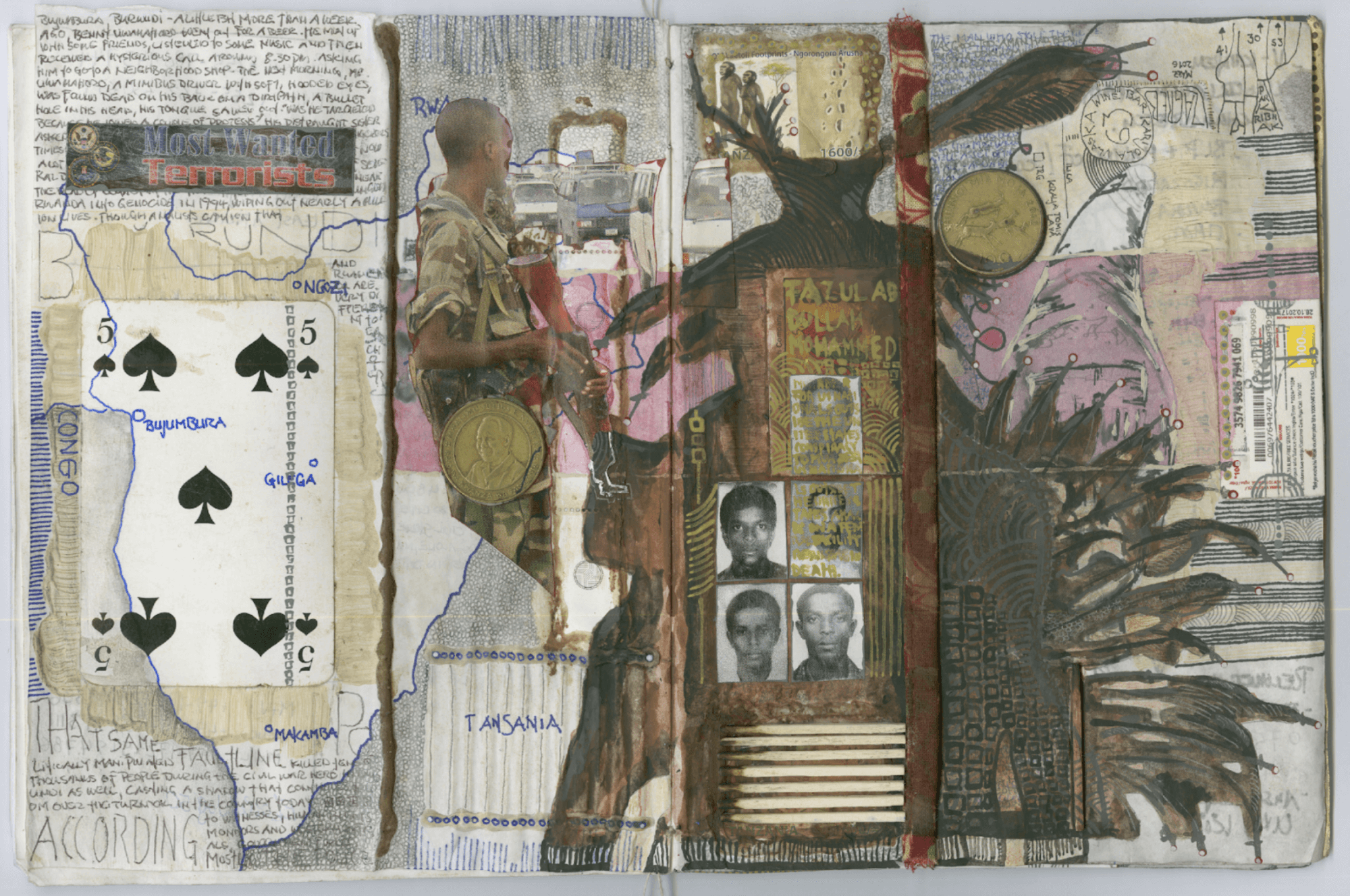

In the West, Qutb isn’t known for his theological treatises on Islamic ethics, but as the ideological forefather of Al Qaeda. The Americans treated anything connected to Qutb with suspicion. A translation was a crime scene. After 9/11, with the acquiescence of the Tanzanian authorities, they swept into Dar es Salaam. Suspected terrorists vanished into black sites. One of the people they were looking for, Wolf, is the name at the centre of your collage: Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, a man who was wanted for a series of attacks against US targets in the region. The Americans were hunting. They studied the books that circulated outside the wa Mtoro mosque. Many of their agents prayed amongst the faithful, performing salat while watching the Ummah with suspicion. “To catch a terrorist,” one counterterrorism expert told me, years later, “you have to think like them, eat like them, dream like them.”

What’s the difference between a writer and a spy? I, too, was trying to understand the translators and their world. I wanted to think their thoughts with them, break bread with them, and know the content of their dreams. That, I thought, was the writer’s duty.

I remember asking one of the translators about 9/11. He had watched the Twin Towers fall on CNN. “Almost immediately,” he said, “they blamed us.” “I had never thought of Islam as political before,” he continued, “but now the television was calling me a terrorist.”

How to live when someone else has named you? Qutb taught the translators how to wrest the name of Islam back from the Americans, and fashion a sense of their own destiny.

I spent a month with the translators, discussing the nuances of fiqh and Islam’s place in Tanzania. Soon enough, I left, as I always do. And soon after, some of the translators were arrested. The others viewed my departure with suspicion. It could be a coincidence, of course.

2021. Jur River Valley, South Sudan

At dusk, I was in a small hotel in Tonj South, writing up my notes after two weeks of traveling through the conflict zones of Warrap, the home state of South Sudanese President Salva Kiir. The next day, I would drive to Wau and get a plane back to Juba. I wasn’t looking forward to returning to a world full of diplomats sipping gin and tonics by the pool and chatting about atrocities. Then I got a call: the UN had failed to book me on the flight to Juba. I needed to go back. Briefing those diplomats was part of my job. In desperation, I called one of South Sudan’s commercial carriers. There was a flight, but it left extremely early in the morning. We would have to travel immediately, though the road was uncertain at night, and the Jur River Valley full of bandits. I stepped out of my room to drink tea and confer with the team I had haphazardly assembled over the past two weeks. My driver, Marchiano, the veteran passer of innumerable checkpoints, a man possessed of an ice-cold stare acquired during a decade driving for one of Darfur’s leading militia commanders, nodded.

“We go?” I asked.

“We go,” Marchiano replied.

A few weeks earlier, in Juba, the diplomats had been moaning about Kiir. He doesn’t build anything. The country has been abandoned. Doesn’t he want to leave a legacy? I mulled over the diplomats’ questions as I drove through Kiir’s home state, riven with violence. The cattle raids came at dawn. The river-crossings were strewn with soldiers that blocked aid convoys reaching opposition groups, in an effort to starve them out. The result? What the humanitarians called “pockets of catastrophe.” Small famines, unlikely to make the news. Almost all of Warrap was a frontline in a war that involved no tanks and no nation-states, but contained eruptions of intense violence that faded into a background of old men drinking tea under cuei trees and cows wandering in search of pasture.

What is Kiir doing? I sat under the cuei trees and asked the old men. It’s simple, they said. He is trying to survive. That’s what soldiers do. They try to survive.

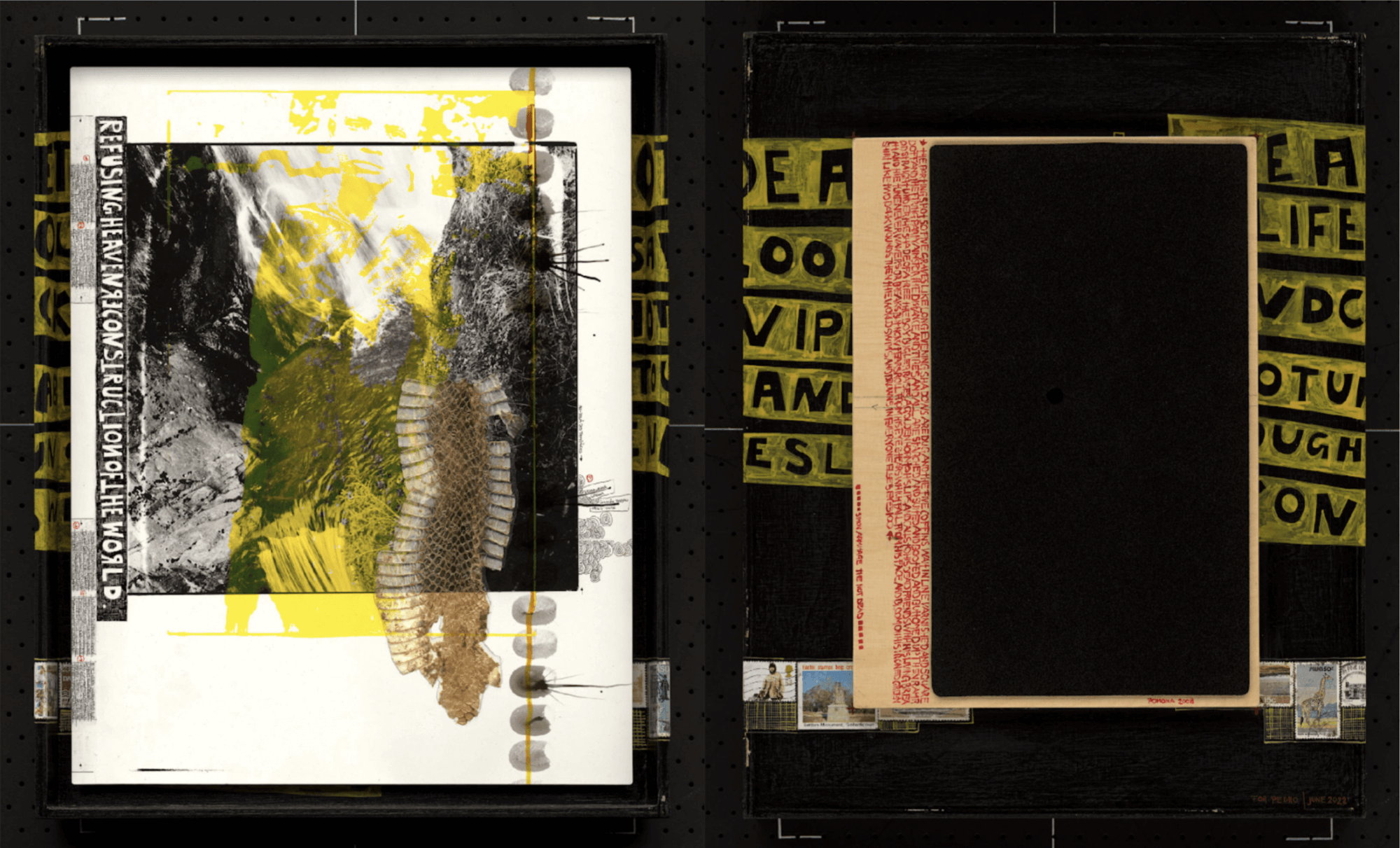

In your fourth and last collage, Wolf, you cite Simon Armitage’s poem, ‘We are the Not Dead.’ It reads like this:

we worshipped Britannia

We the undersigned put our names on the line for her

From the day we were born we were loaded and primed for her

Prepared as we were, though, to lie down and die for her, we somehow survived.

I’m sure such proud patriots exist, but I have to say, I’ve never met them. I don’t know these sad soldiers who curse life and wish for oblivion. I’ve known young men who have joined militias in search of enough money to build their lives. I’ve known conscripts, from Sierra Leone to Sudan. But living by the gun is not a calling for them—it’s a means of survival, just as it is for Kiir.

They are the not dead, these young men in search of life, because their primary injunction is: do not die. Wolf, you must know the euphoria of being in battle, being close to death, and realizing: they are dead and you are not. The victims have died but here I am. This is what I understand to be the meaning of your collage’s title: ‘The Refusal of Heaven.’

I was very ready not to die and extremely anxious to set out on the road to Wau before it was too late. Marchiano had other ideas. He was convinced that chickens are cheaper in Tonj South than in Wau. It was approaching Christmas, and he told me he wanted to leverage the price differential to make some money. We rushed to the market. Chickens were loaded into the back of the truck.

“We go?”

Not yet.

Somehow, I had acquired an officer from the National Security Service (NSS) as part of my motley crew. Deng had taken a liking to me (and was no doubt reporting on what I was up to). He insisted that we first head to the NSS barracks. AK-47s were carefully loaded into the back of my truck, ensuring that they didn’t disturb the chickens. Then a senior NSS officer ran out with an envelope. He looked askance at Deng, and asked me to deliver the cash to a colleague in Wau. “For Christmas,” he explained, sheepishly.

“We go?”

“We go.”

Finally, we were off, past the last checkpoints on the outskirts of town and into the blackness. In the Jur River Valley, the foliage was high on either side of the road, and we stared out, conjuring rebels from the shadows of the trees in the truck’s headlights. The chickens seemed unperturbed. When we finally reached Wau, around 3am, we forced a bar to open and drank warm, sweet beer in the cool of the night. We were alive. And it was fucking fantastic.

I can understand risking death for guns, Wolf. Even for chickens. But what of us? Taking pictures and writing down words in warzones. We remain mysterious to me.

Your images provided me with an escape route, Wolf, out of my own paranoia, as I sat sweating on a bed in Juba. I didn’t take the road to Darfur, but I did travel back into my memories. My ramblings have investigated crime scenes, but they also constitute one. What have I been doing?

Bumping along the road to Wau, I tried to take notes in the dark, convinced, with the devotion of a fanatic, that all this must be recorded, and that in that documentation, somehow, life would be redeemed. From what, I don’t know. I’m not religious.