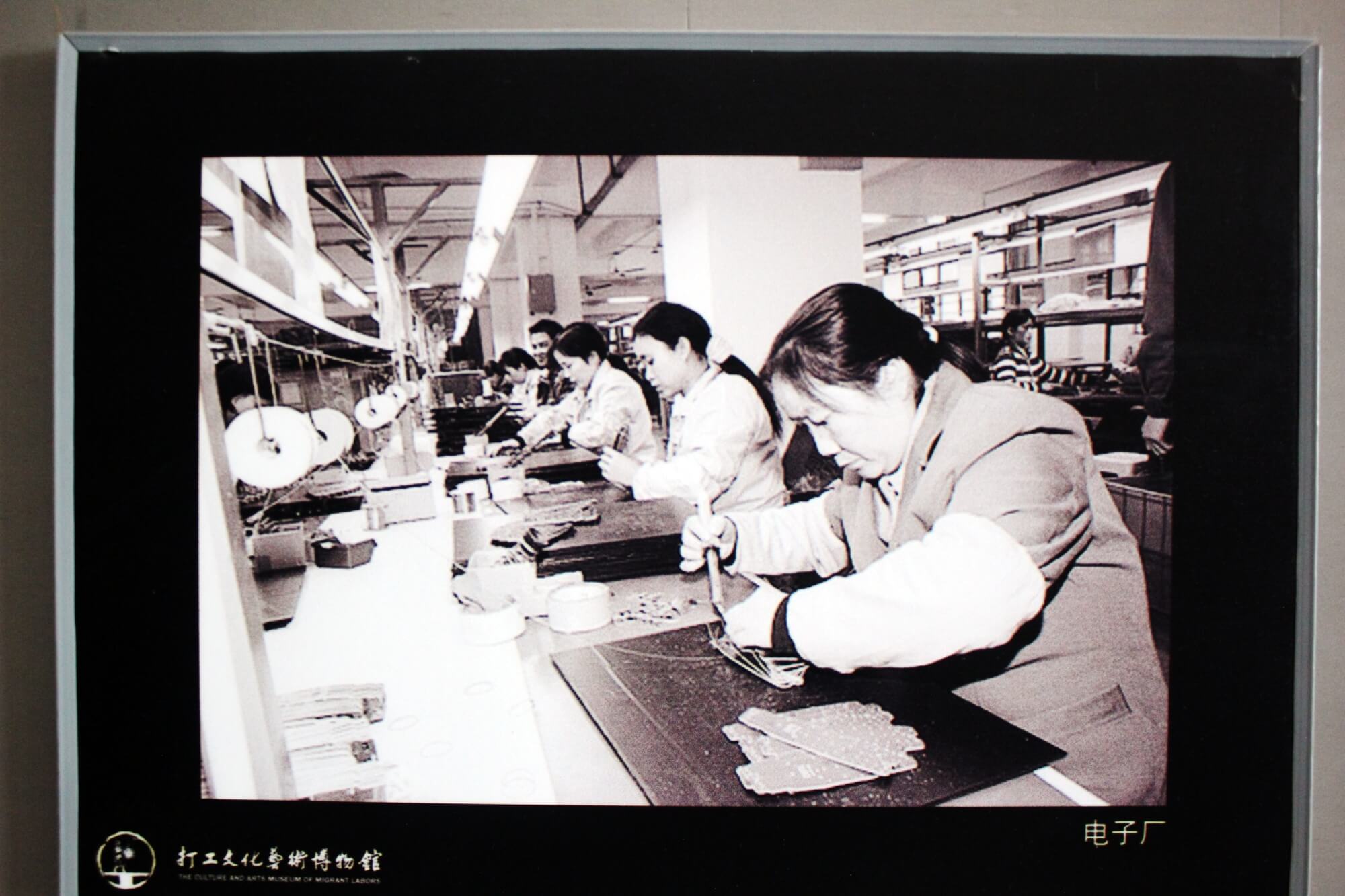

Header image courtesy of the Migrant Worker Culture and Art Museum (打工文化艺术博物馆).

Zheng Xiaoqiong 郑小琼

Truth

Truth, as wild and as lush as the sea

hoists its huge waves to crash down and cleanse

useless poetry, so weak and constrained

A red heart glows like grains of salt brightened in the dark

by lamplight a storm is as maudlin as mercury

it is slow to speak and keeps an ancient silence

Between its light and gloom there seems to be

an ineffable power that unveils the mirror to the truth within

seeping into history as mist gravel silt

nihilistic twists and turns the lies of authority

There’s still a power from truth that forces ripples out

真理

真理有着大海的狂野与丰盈

它卷起巨大的浪花冲刷着

无用的诗歌如此软弱和局限

鲜红的心脏有如灯照亮黑暗中的

盐粒 风暴有如感伤的水银

它不善言辞会保持古老的沉默

在它明亮与晦暗之间 仿佛有一种

莫名的力量揭开藏在镜子后面的真相

渗进历史的雾气 沙石 淤泥

虚无的曲折与困难 权力的谎言

有一种力量强行从真理中漫开

2011

Stuck

One lone star is stuck in my throat scalding tumultuous

Thunderclaps are flowing in my veins In the dark, the crooked

moonlight shines upon a silence Saturating my blood

are cowardice and coyness One passionate heart is entrusted to the sea

Let it float in that darkness of infinite blue At darkness’s

terminal I encounter: earth and faith But they cannot

soothe pain or resolve misfortune Feeble life still

endures such cold apathy and scorn Rising out of my pores like smoke

is a cry useless pity in poetry lines The Han language gave me

a soft yet hardened heart If my fury

deepens any further that iron nail hidden inside my body

will pierce into the dark side of this era like a massive wedge

卡

一颗星辰卡在咽喉 灼热 汹涌

鸣雷在血管里流动 在黑暗中弯曲的

月光 照耀着寂静 血液里饱含的

懦弱与暧昧 一颗激烈的心交给大海

让它飘在蔚蓝无边的黑暗中 在黑暗的

尽头 我遇见:大地与信仰 它们却不能

慰藉疼痛 和解不幸 弱小的生命还在

承担着无情的冷漠与嘲讽 毛孔中冒烟的

呼喊 诗句中无用的悲悯 汉语给我

柔软而坚硬的心 如果我的愤怒

再加深 藏在我体内的那颗铁钉

会像一个巨大的锲子钉在时代的阴影里

2011

Wu Xia 邬霞

Midnight

The night has closed its eyes, my dorm-mates have all started dreaming

Only my eyes are wide awake

In my heart, a little sparrow is frolicking

Changing into the strappy dress from the night-market haul

I climb down my bunk-bed ladder

walk out the dorm, go through the corridor

and come to the bathrooms at the end of the hall

No one is inside the toilets

I go into the shower stall tucked deep inside

The window opens its arms to embrace my shadows

I smile in front of it, and turn,

Right now, I am still a girl

夜半

夜已合拢双眼,舍友们已入梦

只有我大睁着眼

心里有一只麻雀在跳跃

换上夜市买来的吊带裙

我从床梯下来

走出宿舍,穿过走廊

来到走廊尽头的洗手间

厕所里空无一人

我走进最里面的冲凉房

窗户张开手臂拥抱我的身影

我在它面前微笑,转身

这一刻,我依然还是少女

2015

Who Can Stop My Love

Outside the car window, beautiful scenes flutter by frame after frame

Like arrows shooting into my heart shaft after shaft

The rental has been locked inside a dark corner

Being in Shenzhen for 18 years, home town is now some other town

I wake every morning with Shenzhen’s morning, and at night I fall asleep

With Shenzhen

I love her morning-like liveliness, her golden sunlight.

The flowers blooming one after another all four seasons

The evergreen trees and grass,

I love every inch of her growing. This love seeps

into pores, into skin, into blood, into marrow

Even if the resident permit of this city does not have my name.

谁能禁止我爱

车窗外,一帧帧美景从眼前掠过,

像一支支箭射进心底。

出租屋已锁进幽暗处。

来深圳十八年,故乡反倒成了异乡。

我每天与深圳的清晨一起醒来,与深圳

的夜晚同眠

我爱她的朝气蓬勃,金色阳光。

一年四季轮番开放的花朵,

长青的树和草,

热爱她的每一寸生长。这种爱渗入

毛孔里、皮肤里、血液里、骨髓里,

即使这座城市的户口簿上没有我的名字。

2015

My hands are not empty

I have no house no car no cash

I have my dad my mom and my daughter

and everything else in this dinghy rental

as well as the potted aloe plant on the balcony,

and the surprising tomato seedling peeking out

I have the right to walk around freely

These beautiful sites I walk by belong to me

I also have my writing

in my most painful hour

holding my body, hanging by a thread.

我并不是一无所有

我没有房子车子票子

我有爸妈和女儿

还有这破出租屋的一切

和阳台上芦荟盆里突然冒出的番茄秧

我有自由行走的权利

这沿途的风景是属于我的

我还有我的写作

在最痛苦的时候

扶着我摇摇欲坠的身体

2015

Lan Zi 蓝紫

Lowered into the dust

Standing there on the 6th floor rooftop

Yelling that if he doesn’t get the two-year’s pay owed to him

he’ll jump

is Old Zhang from our village

Two years

at this construction site

He abandoned his farmlands, and left behind his wife and children

to join his fellow workers, swapping 700 days and nights’ worth of sweat

in exchange for this forest of tall buildings

Right now, on the rooftop he built with his own two hands

That body in an old, yellow-stained t-shirt

makes the sky seem helpless and barren

His lofty shadow, falling onto the rubble-strewn ground

is lower than dust

低入尘埃

那个站在6楼楼顶

扬言说再不付拖欠两年的工资就要跳楼

的人

是我们村里的老张

两年

在这个建筑工地

他荒废了田地,远离了妻儿

与工友一起,将700多个日夜的汗水

换来这片林立的高楼

如今,他站在亲手建造的楼顶

穿着黄旧T恤的身体

将天空映衬得无助又荒凉

他高高的影子,投在遍地瓦砾上

比尘埃更低

6.28.2015

Blind

If the world continues to be this superficial, crazed, disingenuous,

I’d rather I couldn’t see. — prologue

1

Time is full-bodied, I am the moments missing a corner

In the days that passed

there are too many missteps

my laziness, dependence, apathy

For survival, I am a blind moth

slamming from one window into another

Those who are favored by fortune

in their contentment and enjoyment let time fly by

The wheels of desire crushes over gazing eyes

City life

is even smaller than the life of a mountain peasant woman

I close my eyes, and push away an entire sky

2

Let words march forward in legion

from one rotting mausoleum

into a whole chapter of broken sentences to hide

and complete an exile of the self

a calling of the self

a gazing of the self and a consolation of the self

I am looking, feeling moved,

watching myself, passing old dreams of wildflowers and cherries

passing those trembling feathers

leaving wondrous imagination behind

in the orchards and the fields

Lands are tilting, clear waters flow

Lines of poetry, like winds of nature, rise

……

3

All heartsickness comes from one’s hometown

comes from this life of wandering

Hundred and thousand miles of roads

collect all those footprints stained in dust

We are now far away from mountains, valleys, wilderness

away from trees, flowers, grass

away from streams and the call of birds

My entire life is spent rushing on the road with my head down

I can’t tidy up my complexion

Home is forever ahead, and keeps on seducing me

to drum out my wings, to commit an error

4

This is a city where you cannot see the smoke

One and another blurry faces

are one and another gloomy temples

On those many strange faces

restore oneself repeatedly

One minute, even one minute will suffice

Let me see these days clearly

and see a different human kind

Waving their somber arms

to tear apart the riddle-like air

and pluck out the gold inside sunlight, one, and another

Gusts and gusts of air are flooding forth from afar

Neither null, nor pitch black

5

In places where youth lost its way

we struck all kinds of poses

Just another method of sojourning

Just busy mess and clownery

Chasing after sunlight, just an elaborate lie

just another futile hunting scene of ambush

6

Pain is magnetic, it attracts our ancestors

and forces itself upon our feeble shoulders

Because of pain, life again and again becomes more complete

Loneliness, failure, distress

the three heavy layers of sin in life

floating down the stream of a little path

I’ve entrusted loneliness to memory, and got gladness in return

entrusted failure to living, and got tears in return

entrusted distress to flowers, and got fruits in return

In the end, I entrusted myself to myself

standing alone, in a massive thunderstorm.

盲

如果世界这样持续浮躁、疯狂、虚伪、我宁愿我看不见。——题记

1

时间饱满,我是缺角的光阴

以往的日子

有太多的过失

我的懒惰,依赖,无情

为了生存,像一只盲目的蛾

从一扇窗户撞向另一扇窗户

被生活青睐的人

在满足与享乐中放跑光阴

欲望的车轮,辗过张望的双眼

城里的生活

比起山野农妇的生活更加渺小

我闭上眼睛,将整个天空推开

2

让文字列队走出

从一座腐朽的陵墓中走出

躲在一章残句中

完成一次自我放逐

一次自我呼唤

一次自我凝视和一次自我安慰

我注视着,感动着

看着自己,经过野花与樱桃的旧梦

经过那些颤动的羽毛

将神奇的想象

留在果园与村野

土地倾斜,清水流淌

诗句像自然的风一样升起

……

3

所有的心病都来自故乡

来自这漂浮的生活

千万里道路

领走沾满灰尘的脚印

我们已经远离群山、峡谷、旷野

远离树木、花朵、青草

远离小溪与鸟鸣

我的一生都在低头匆匆赶路

收拾不好自己的面容

家在永远的前方,不停地诱使我

鼓动双翼,犯下过错

4

这是一座看不见硝烟的城市

一张张模糊的面容

是一座座幽暗的神殿

众多陌生的脸上

将自己反复还原

一分钟,仅仅一分钟已经足够

让我看清这些日子

看见另一种人类

挥动着阴暗的双手

撕破谜语一样的空气

一把把摘取阳光中的金子

大片大片的空气从远方潮涌而来

不虚无,也不漆黑

5

青春沦陷的地方

我们做出了各种姿势

不过是寄居的一种方式

不过是忙乱与鬼脸

追赶阳光,不过是一场欺骗

不过是一场徒然的围猎

6

痛苦是磁性的,它吸引着我们的祖辈

强加在我们孱弱的肩膀上

因为痛,人生一次次变得更加完整

寂寥,失败,愁苦

生命中的三重罪

在一条小路上漂流

我把寂寥交给回忆,用来换取欣悦

把失败交给生活,用来换取泪水

把愁苦交给花朵,用来换取果实

最后,我把自己交给自己

独自站在巨大的风暴之中

6.6.2007

Translator’s Postscript:

The Museum:

In May 2023, the Migrant Worker Culture and Art Museum (打工文化艺术博物馆) in Pi Cun (皮村), Beijing, was closed down and scheduled for demolition after 15 years of operation. It was the only grassroots museum to document migrant arts and culture in China, and had been part of the cultural heart of many Beijing-based migrant laborers, activists, artists, and researchers. In the summer following the museum’s closure, the region surrounding Beijing experienced significant thunderstorms and flooding. Some of the warehouses that temporarily stored the displaced artworks and other archival documents were impacted, permanently destroying many of these artifacts.

The poems included in this series are part of a larger online archival project that was started in response to this series of disastrous events. I first heard of the destruction of Pi Cun Museum’s displaced materials through a friend-of-a-friend. لارا (Lara) had been one of the volunteers at the museum and was able to photograph a lot of the material prior to their destruction. After the floods, she launched an archival and translation project to preserve the art and literature of Chinese migrant workers (a genre commonly labelled as “migrant worker literature”). Given the sensitive nature of labor-related discussions in China, the translation process was atomized and anonymized. Members of the translation collective interacted with each other under pseudonyms and through newly registered online accounts.

At the time of writing, لارا (Lara) and her friends have made the collections of the Pi Cun museum partially available on this website.

The Poets:

The poets featured in this series were not directly related to Pi Cun Museum, but had previously worked in various factories in Guangdong province around late 2000s and early 2010s. Some of these poems were written while the poets were still full-time or part-time workers at the factory, while others were written years after they left the factory line. All three poets are still active writers, and their writing careers have branched beyond the migrant worker literature genre. I asked the poets how they would like to introduce themselves, what they felt about re-reading their earlier works, and about their current concerns. Below are their responses, edited for clarity and brevity.

Zheng Xiaoqiong 郑小琼

I am currently working for a literary magazine. I am mostly an editor, and I occasionally write. On the weekends, I go to the industrial areas to talk with the workers and try to do something for them. I still care about the life of working class people, especially how the globalization of manufacturing has impacted the working class people in South East Asia. Other than the 3 year lockdown during COVID-19, I spend most of my resting time in the city’s industrial zones trying to do something for the workers, so in a sense I feel like I’m still active and present in those spaces. Though naturally time changes many things, including how certain pervasive issues in the past (such as withheld wages from the workers) are now less prevalent.

Now I care a lot about the social security and welfare of working class people. 25 years ago, when I first entered the factories as a worker, I belonged to the third wave of migrant workers; now many of the workers who entered the factories before I did have reached retirement age, so I pay a lot of attention to the social security and welfare of these older generations. As the economy changes, many new problems emerge, such as whether freelance workers, gig workers, food and other delivery service workers are given any social security benefits. Every era has its own problems, all we can do is try our best to do something.

Thank you so much for everyone’s interest in my poetry. In truth, “migrant worker poetry” is only a small part of my poetry writing overall. I’ve written many poems about a myriad of different issues, which I hope can be published in translation so I can share them with more readers.

Wu Xia 邬霞

I started my writing career by writing romance, and I later switched to writing migrant worker literature, including non-fiction and short stories. This past year, I wrote poems almost daily, spending very little time on fiction or prose. I spent much of my time trying to pass the vocational qualification certificate exams in order to apply for hukou (legal resident registration in a city), so that my children can go to public school. I still haven’t passed the exam. There’s so much I haven’t managed to do. I’m also trying to find a job right now. I’m sending out resumes online.

I want to write a long novel—that is what I’ve always wanted to do. I have to wait another year to take the exam, and by that time my children will also be older. After I have solved these problems in life, I will have some spare time to write my long novel.

To my readers, thank you for your attention, appreciation, encouragement and support. It is your company that makes this long road of literature less lonely, and it is you who gave me strength to move forward. I will continue to work hard and create better works.

Lan Zi 蓝紫

I’ve always been cautious about the label of “migrant worker poetry.” In fact, during the time period when “migrant worker poetry” was at the peak of its popularity, I wasn’t really in the midst of the scene, but was rather at its margins. Indeed, I was living in a place where migrant worker poetry emerged, and “migrant worker” was one of my identities at the time. When I joined the writer’s association of Dongguan and became an editor in a literary magazine, I participated in activities related to “migrant worker poetry,” but I personally reject the label of “migrant worker poet” (or any label, for that matter).

Around 2015, I wrote a series of poems about laborers from the lowest classes. Besides the construction workers in “Lower into Dust,” I also wrote about shoe-shiners, trash-collectors, the “spidermen” who clean the windows of skyscrapers, the hostesses in hotel bars etc. I felt that in our society, they worked the hardest and most undesirable jobs, but they are part of the “voiceless,” because it is very hard for them to speak out, and very few people acknowledge their hard work or their most dire concerns. As for my poems, I would not dare to claim that I can speak for these people, but I feel like I can at least speak about them and the problems they face, record their existence.

Recently, besides my usual poetry writing (I write around 30-50 poems a year), I’ve been working on poetry criticism. There was a period of my life more than a decade ago when I wrote poetry criticisms regularly, but I stopped doing that for a while until I picked it back up in 2022. My criticisms are usually inspired by some of my own predicaments while writing…

The Formatting:

As you can observe from the Chinese text, all three writers use punctuation quite sparingly. In order to avoid total confusion, I have capitalized what seems to be the grammatical “start” of a sentence in the original. I have also replicated places where the poet chose to connect and separate each clause through spaces instead of punctuation.