This poem is based on thirteen conversations with Moscow activists who were imprisoned for participating in demonstrations — many in the Bolotnaya Square March of 2012 — as well as their children, wives, and friends. I wanted to understand the conflict or harmony they felt between their sense of responsibility to their private loves and the ideals that drove them to sacrifice and to convey, if possible, the epic quality of ordinary lives. Most words are fragments of their speech transcribed from a recording and translated from Russian. You can read the transcripts at the bottom of the document. Some, because imprisonment makes face-to-face conversation impossible, are translations of published sources. Some memories are my own.

One of the heroes of the poem, Ildar Dadin, died on October 5, 2024, fighting for Ukraine on behalf of the Free Russian legion. His battle name was Gandhi.

For Neil and my grandmother.

Invocation

Whisper me, oh muse,

Dare will I sing

Another’s stolen

Tongue.

Thirteen Conversations about Love

You are a person of ideas, a person of conscience. But they?

If Anastasia had cared she would have held the sign with you.

She would not have allowed you to get arrested alone.

You are a hero, of course,

but do they deserve you?

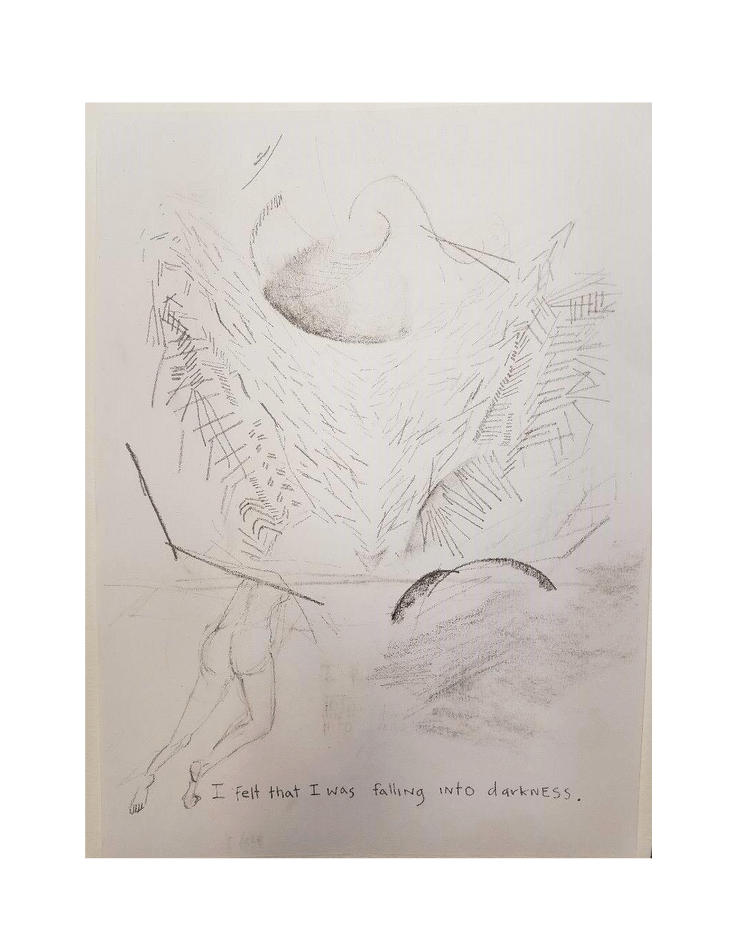

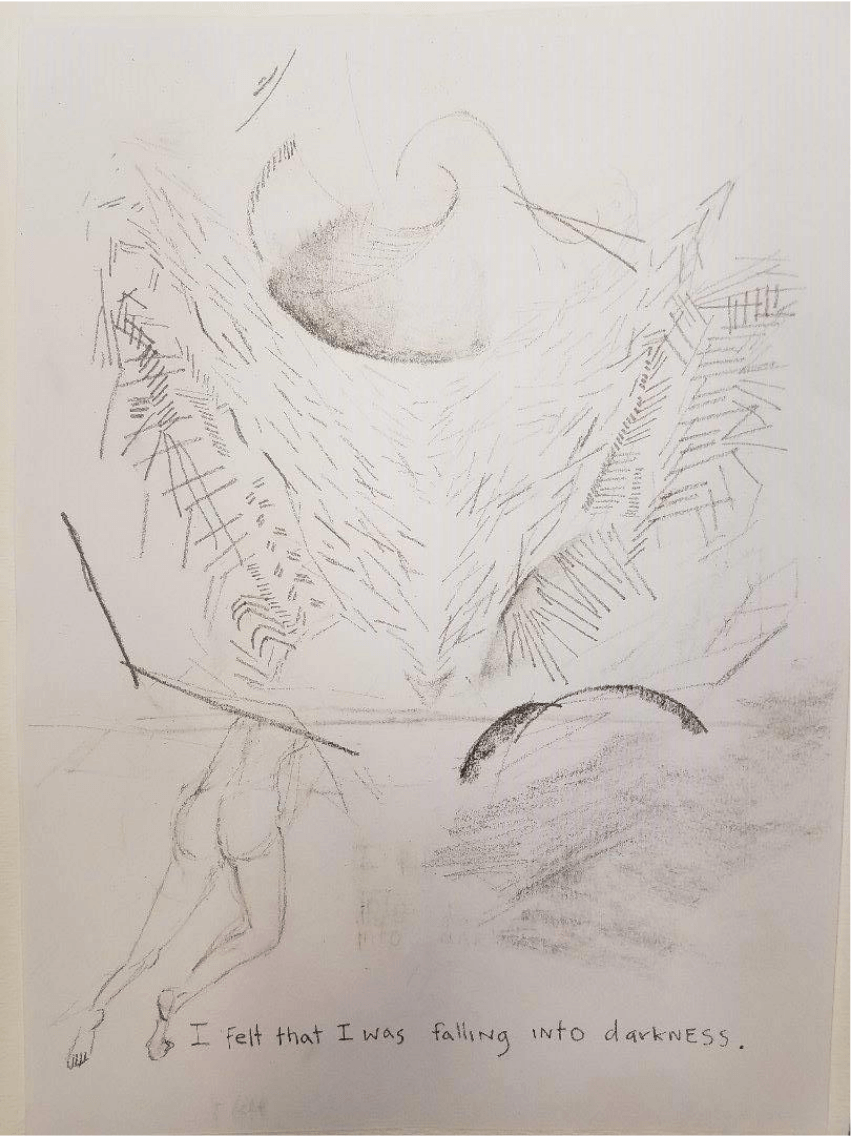

I could not inhale or exhale, and I felt that I was falling

into darkness. Nobody told me about the convulsions or the foam in my mouth,

I only dimly felt,

as if through fog, that I am being carried

and undressed and then I felt an injection in my buttocks.

Who am I to have

gone? To play

the hero for a day?

While Ildar, Ildar

cannot go away?

Like Ildar I am

confined to stay

because my fear

and pride won't

let me go.

Why do you want to talk to me? I am just a regular person.

I know.

I.

You ask me," How are things going?"

So I got out of prison

two months ago now

so I have not found a job but I am looking

and my wife says

that if you are planning to continue all this then live by yourself.

I am getting evicted.

Of course prison changed her. She didn't know

it was so serious before. I would go to demonstrations

and she called it having fun

that I just go to have fun. I didn't think

that I would get arrested and go to prison. Well, I knew

that I would get arrested, of course, I was arrested many times

about going to prison

I knew that it was possible. You see, it's one thing to understand

that something is possible,

you can go out and get run over by a car,

we all know this,

but when it happens

it is already something completely different, right?

II.

This is a philosophical question,

What do you live for?

I asked my son.

Then explain to me why nature needs

Krivov, Vasily

That is his name

He was silent. Think about it

I said. A few days pass,

even a week

he didn't forget somehow

Then he comes up to me and says

I was thinking and thinking

and I couldn't understand why

I am needed. Well,

I couldn't explain it to him.

III.

I was four or five,

I don't remember exactly

when I went with my parents to the woods

to play near the house.

No, that's not it. I was little so

it all mixed together in my mind

GKChP and what happened in '93.

In the forest,

as I began telling you,

I heard shots being fired and

even though it was outside of Moscow,

you could still hear the guns.

My parents blamed it all on me.

They said that it is because

you are behaving badly that the war

is starting. And I thought to myself

how could me behaving badly

have anything to do with the war?

IV.

Flags!

Pyrotechnics!

Problems with cops!

They just don’t play football…

Otherwise it’s practically the same thing.

You pay fifteen grand

An exercise yard with a

Woman – for an hour or two –

A cell with no roof.

Pencil

Paper

Toothbrush

Bread

Water

Yesterday – Chelyabinsk: packages for single mothers.

Today – girls from Dagestan.

Alone

To be honest, I am probably not a very good person. I know that if United Russia asks me to do something bad in return for freeing my husband

I will do it.

Just because he is more precious to me than all the others.

I don’t know who came to Ildar’s Mother

and started telling her “Your son is a hero.

You should be proud of him.”

And Ildar’s Mother asked,

“Would you be happy if your children

were sent to prison?”

And the woman answered,

“For a long time now, my children

have been living in France.”

I do not even know what hurts me,

I am not formulating this well, I just understand

that it is very hurtful when people can write:

“be strong, everything is going to be O.K.”

but at the same time, they are not ready to do

anything and I begin to feel that they practically sent

him to prison in order to make

him into some sort of martyr.

A dog in the apartment alone,

does not go to the bathroom

because no one walks her. So

she wouldn’t suffer as much I take

her to live at the dacha,

we are riding the commuter rail

and we get off at a station where there is a field

and little wooden houses,

and I have one wish that when Ildar gets out,

I would move to a little town like this one

and live with him and the dog

and raise children

and just live.

VI.

This great hell helped my

husband and me remember

and our two little sisters

that they need each other and

Papa and I need them too.

There were two of them.

The Grandfather Frost which was Mama was snazzy.

But of course.

All the Grandfather Frosts were.

So, I really like tiramisu cake and on New Year’s Eve a table appeared

and this big box which was all tiramisu. And I ate it all

almost by myself. And I liked it.

They all like it, but I like it more.

I have Anna, my sister, and she just eats everything sweet.

Practically, if something has sugar,

she likes it,

and when she was little she put sugar in her soup.

But I especially like tiramisu.

VII.

The back of the head and the temples

but not with a fist

with an open hand

with their feet but not with the toe

of their boots but with the flats of their soles on

my body, on my feet,

on the inner parts of the thigh

until you fall down

until you agree with what they are telling you

You are worthless

You are a faggot.

Look he is even smiling…

VIII.

It is a state of mind when you can’t not do it. And when you do it you do not think about the consequences. If you think about the consequences, you will never do anything.

…You really had to complain didn’t you…

…Made yourself a faggot in the eyes of the world…

…You will save no one…

You understand, it is truly a question of love.

Because love can be closed,

shut off

so I love my family and you can all go to hell,

this does not touch me.

…You love Masha Alekhina,

but your own grandmother you do not love…

…My heart is bad…

…Do you want me to die?…

How much can you fit inside yourself?

Love has volume. “They have a big love,”

people say. What does that mean, big?

Can love be measured

by its dimensions? Big, deep, high

feeling.

Where are those dimensions?

…You really had to complain didn’t you…

IX.

Even though I did nothing illegal

because regardless of what I did

whether it was legal

or illegal, even though in the moment

I did not think there could

be any consequences, even though

I did not consciously understand

consequences were possible,

still I fully accept

“Did you think about Father Vyacheslav?”

“Did you think about what would happen to the Holy

Father if they took you away?”

(I could not forgive her this)

grandmothers

are alive somewhere

getting old

and I was so afraid that I

just wouldn’t make it to see them,

before getting out,

Afraid that one of them would not

be there,

only I.

X.

Let’s imagine a person likes candy

and for a long time candy she eats

and then they take it away

and give her salty foods,

and give her bitter foods,

but for three days

they let her eat candy again

for three days

until they take him

again. I miss him more.

XI.

In the second minute I say, “I agree to everything.” After fifteen minutes

I prayed that they come sooner. I remember that in the second minute

I broke. I was ready to say anything to make them stop.

After fifteen minutes I thought, “Am I ready to give my mother

to them?” “Take her and not me.” And two or three days later when I felt that I was completely broken

ready to give my wife to them if only it would stop I was so devastated

that I did not want to live

but after some time, I remembered again

realized better that I rather than, God forbid, my wife

or my mother… And after I heard the others scream

How do I have a right to leave

If they stay

Am I somehow better than them

I am ready to be hung by the wrists again

To be broken.

XII.

I think if it weren’t for prison

we would have gotten divorced,

because prison is like a filter

for a photograph

details that you had no seen before

light up,

remove what is not important.

“Wow, what a person,”

you look and think,

“So, this is my husband?”

A person who is strong

A person ready to suffer

Yes, back to back

it gives comfort

when you trust that a back is

behind you.

XIII.

When 2011 happened, the year of protests, and 2012,

he was already free

and we promised each other when

all the protests started that we won’t get involved

with them. We’re not going to go anywhere,

no activism.

We talked about it the whole evening

and in the morning, we got in the car

to go to Zvenigorod

to get away and he was behind the wheel and

I was next to him,

we didn’t talk

at all, we didn’t say a word

to each other, we had been talking

to each other the whole day that there we were not going to go.

And then in the morning we got in the car

and went.

Appendix

The following are the excerpts from conversations with imprisoned Moscow activists and their loved ones which I used to write Thirteen Conversations about Love. They have been transcribed from audio recordings, translated from Russian into English, and ordered alphabetically by first name.

Aleksandr, Elena, Maria

09.12.16

Ariella: Tell me how your imprisonment affected your relationships with your family and your friends.

Aleksandr: They only became stronger.

Elena: There is a saying, ‘there is no bad without good’. So this pretty big ‘bad’ helped my husband and me remember how much we love each other and helped our two little sisters understand that they really need each other and that Papa and I need them, and we became a very, very close-knit family. And we also we found a lot of friends which is also very nice. Because many people who didn’t know us before or knew us, but weren’t close, wanted to help us. This is the bright side of it all happening.

Ariella: The people who became your friends, how did they approach you or what did they do that was important to you?

Elena: They helped in different ways. Some just told us kind words. Some wrote to Sasha, helping him a lot by that.

Aleksandr: Yes.

Elena: Of course, they helped me and the girls. They helped me find a job and gave them presents for New Years. Even Grandfather Frost 1 visited us. Many beautiful things.

Aleksandr: Yes, it is important to acknowledge that the support was significant, for which [we tell people], Thank you!” During my imprisonment, after my imprisonment.

Ariella: Could you tell me about Grandfather Frost?1

1. Grandfather Frost (Russian: Дед Мороз) is the Russian equivalent of Santa Claus who brings presents to children on New Year’s Eve. During family celebrations, it is most common for the father to play the role of Grandfather Frost.

Aleksandr: Of course. [Chuckling.]

Elena: Father Frost came. Not me [dressed up as] Grandfather Frost but it was, I think… Maria: Oh yeah there were two Grandfather Frosts. The one which was Mama was snazzy.

Elena: Of course. All the Grandfather Frosts were good. So Grandfather Frost came. Tell us yourself what two big cakes he brought.

Maria: Oh yeah. So, I really like tiramisu cake and on New Year’s Eve, a table appeared and this big box which was all tiramisu. And I ate it all almost by myself. And I liked it.

Ariella: And the other members of the family do not like tiramisu as much? Maria: They all like it, but I like it more.

I have Anya, my sister, and she just eats everything sweet. Practically, if something has sugar, she likes it, and when she was little she put sugar in her soup.

Ariella: Soup?

Maria: Yeah… but I especially like tiramisu.

[…]

Elena: Information travels very slowly. Sometimes I did not know how he was feeling for a week, two weeks. This was very hard, of course. The visits were rare.

Ariella: How many visits did you have in a year?

Elena: They did not allow visits at first, by the way.

Aleksandr: First there were no visits. They did not give us any from February to May and then twice a month.

Elena: About twice a month, I have to say that one time we came for nothing, sometimes I came with the girls, and for the second [visit] his parents would come, so I would see him once a month.

Aleksandr: Afterwards, during the trial, they also cut off our visits.

Elena: Completely, right?

Aleksandr: Yes. From the 7th, no, the 14th of April to August 18th…

[Voice muffled by noises from the street]

Ariella: What about visits in the prison colony?

Aleksandr: In the prison colony there is one short visit once every two months and a longer visit once every three months. Well, if they don’t have anything against you. Because they can take anything away. And also if a person works well sometimes…sometimes you get an extra visit. I didn’t get one, so… Lena brought the girls once.

Maria: The visit was three days. It was really awesome.

Ariella: Could you tell me about what that was like?

Elena: A long visit is when…

Aleksandr [speaking at the same time]: ‘A long cooking.’

Elena: First of all, you can cook homemade food, take practically anything with you, with some exceptions bring your own things, and you come in the morning, go through a certain procedure of handing off the groceries , entrance, inspection, and then we find ourselves in a modest hotel on the grounds of the prison colony. It’s quite livable, tolerable overall. There is a place where you can cook, all kinds of amenities, even a washing machine. And rooms that are pretty decent for living in comparison to the barracks. The only thing is, the reason the girls were there only once, is that it was cold. I was afraid that in those three days the girls would catch a bad cold.

[…]

Ariella: Could you tell me about how it was?

Maria: Well, it was awesome and at the same time bad. It’s like forbidding someone after a long…so imagine a person likes candy and he eats it for a long time and then they take away the candy and feed him with salty things and they are not only salty, but disgustingly salty. So for the rest of the time he eats only bitter and salty foods. And then again, for three days, they let him eat candies. And then they take them away again. That’s what it looked like.

Ariella: So it was even more painful to leave, you miss him more.

Maria: I miss him more, but it was also good because candy is delicious after all. They gave us candy.

Elena: It was the first visit in two and a half years, right?

Maria: Yeah. But it was really awesome, we played different games.

Anastasia

09.03.16

Ariella: People like Ildar, do you think that Ildar was used too?

Anastasia: I think that Ildar was also used. For example he worked as a volunteer in Navalny’s election campaign and he didn’t get anything from it. He believed that he was helping something big and good and then he saw that, let’s say, Navalny is not the most decent person.

Ariella: And he stopped and left.

Anastasia: Yes. And in addition to that, he went to protests of different organizations, and so he stood with some kind of flags, articles were written about this, the organizations benefited.

Ariella: What kind of flags? Ukrainian flags?

Anastasia: And Ukrainian flags too. And afterwards, it was very painful when one woman, I don’t even know who, came to Ildar’s Mother and started telling her “Your son is a hero, you should be proud of him.” And Ildar’s Mother asked, “Would you be happy if your children were sent to prison?” And the woman answered, “My children have been living in France for a long time now”. Practically, people, opposition activists, maybe, who have made their children safe, who have made themselves safe, they well do not go to prison, they are not planning on going to prison, if something happens they will go away, and practically - I don’t know - they are ready to say that Ildar is such a hero but when Ildar was imprisoned the help ended. So they write that he is a hero but they are not ready to do anything, I don’t know, to do the same thing, to go out with a poster that says Free Ildar, to put a sticker somewhere that says Free Ildar. They are just ready to repeat that he is a hero. I do not even know what hurts me, I am not formulating this well, I just understand that it is very hurtful when people can write: “hold on, everything is going to be O.K.” but at the same time are not ready to do anything and I begin to feel that they practically sent him to prison in order to make him into some sort of martyr.

[…]

Ariella: Before I ask the last question, do you have any questions for me?

Anastasia: No. To be honest, I have a dog but I took her to the suburbs for a time. Because I sit for twelve, fourteen hours in the campaign office, and the dog sits in the apartment alone, doesn’t go to the bathroom, and no one walks her. That is why I took her, so that she would live at the dacha, and take walks, and wouldn’t suffer as much, and when I was bringing her there, we were riding the commuter rail, and then got off at the a station, and there was a field , there were little wooden houses, and I had one wish, that when Ildar gets out, I would to go to a little town like that one and just live with him and the dog, raise children and just not think about any politicians, just…just live with the person I love. Because I am so tired of all this.

Denis

09.14.16

Ariella: On the one hand, it was important for you to take part in the protest and help people who were being beaten, and on the other hand, you are worried about your Mom. Do you feel conflict or harmony between responsibility to your loved ones and loyalty to your political ideals which can put you in danger?

Denis: Yes, I understood the question; it’s a very good question actually. Even though I did nothing illegal, I feel responsible for my actions before my family, before my mother because regardless of what I did, whether it was legal or illegal, even though in the moment I did not think there could be any consequences, even though I did not consciously understand consequences were possible, still I hold myself responsible because only I am guilty of what my mother and my close family had to face all this time and not just face but worry, get sick, I don’t know… because in that time a lot of people, especially my mother, her health got worse, she started to get sick more often, because of worry and with the old people I was afraid, I also have a grandmothers, one grandmother and another grandmother, they are alive somewhere and they’re getting old and I was so afraid that I just wouldn’t make it to see them before getting out. I was afraid that one of them would not be there. I understood that only I was responsible for this. And because of this, yes, I feel responsible.

Now? I don’t know about now. I do not blame myself constantly for this. We had a conversation, of course no one is angry at me or holds a grudge against me, and everyone perfectly understands the situation that I found myself in. But I wouldn’t say it’s quite harmony. We are more calm about what happened.

Elena

09.18.16

Elena: They did not record the arrest, and only made us write an explanatory note. We wrote that we came to the church to pray. [Laughing].

Ariella: But it’s true.

Elena: True. The absolute truth.

And so I had a fight with my friend and I got upset at her because friends were calling and asking, “Lena, how can I help? Do you need anything?” And she called and told me that I am taking care of an elderly person, my spiritual father. And he truly is a person who requires complete…we live together at the dacha. She called and asked angrily “Did you think about Father Vyacheslav?” “Did you think about what would happen to the Holy Father if they took you away?”

Ariella: Did you think that this was just? I guess not because you had a fight.

Elena: I had a fight. I could not forgive this. Because you cannot treat a person like a function. That I am taking care of a person that is dear to her. The fact that I can be arrested and imprisoned, yes? Then I will not be able to fulfill my function of caring which I took upon myself. But this is a function, and I am also a person. I have my own beliefs, opinions, and feelings. And if I was ready to do such a thing, after all, then that means that there is something serious behind it, or I should be considered a complete idiot. But if you take me seriously as a person who makes meaningful choices… I truly couldn’t not go. It was a state of mind when you couldn’t not do it. And when you do it you do not think about the consequences. If you think about the consequences, you will never do anything. And this has to be understood. And if people do not see you as a person, then what is there to talk about? If people see you as a function, you have to do something and now you are not going to do it, and ‘How could you?’ because now you will not be able to do it, all the more because she knew perfectly well that Father Vyacheslav, whom I take care of, writes about Pussy Riot, calls them holy girls, prays for them morning till night, he couldn’t even watch me talk to Masha Alekhina over video chat in prison. You could order video sessions with Masha in the labor colony and I would order them. I would call Father Vyacheslav and say, “Come, you will talk too.” And he would begin to cry and say, “I can’t, you understand? I will only cry at the screen. Because they are there, and I am here. They are there, the girls are there, and I am here, free.” And she asks, “Did you think about him?” I thought about him too, because we were suffering for them together.

You understand, this is truly a question of love. Because love can be closed, shut off: So I love my family and you can all go to hell, this does not affect me. There is a closed type of family and an open type of family. What is special about Venik Dmitroshkin and Yulia Bashinova? This is an open type of family. It is a family with children which at the same time is concerned about the country and about society. They were part of the protest movement as much as they could , and then they left, and made the right decision, but they still care, still live for this on the inside. If two people that love each other or family members that love each other do not open their love to the world, then a penny is the worth of their closed-off love. It is by itself an egocentric love, but this ego can be family, this ego can be two lovers, they love each other and they do not give a damn about anything else, or a person loves his job and could not care less about what is happening in the country. You understand, this openness depends on how wide your soul is. How much can you fit inside yourself? Love has volume. “They have a big love”. What does that mean, big? Love is measured by how deep the feeling is. Love is measured by its dimensions. Big, deep, high feeling. Where are these dimensions? These dimensions depend, in my opinion, on how much humanity you can take into your love. So you either live grabbing onto someone who you love: your family, your work, your nation, your country, or you are open to all humanity and you live all together. And then it is truly love. And so of course when you run to defend someone, you love this person. I really love Nadia Tolokonnikova and Masha Alekhina. I simply love them. My daughter was jealous of them. She would scream hysterically, “You only need your Pussy Riot”.

Ariella: Listen, I can tell you. You are the first person that I can talk to about this. Last year when Masha wrote to me “Can you do a translation? But you have to do it in two hours.” And of course I had never done such a thing before and it was Yom Kippur but I said “OK.” Then my Grandmother gets horribly angry that I want to concentrate and close the door. She says, “You love Masha Alekhina, but your own Grandmother you do not love. You are such trash. I don’t want you to live with me. And … I don’t know…I am trying to understand in myself…I don’t know…I really love Masha too. I am afraid that I am a bad person.

Ildar

11.09.16

On September 11 they first tried to put me in a stress position after I declared a hunger strike on September 10. A stress position is when you are forced to stand two steps away from the wall placing your hands on the wall with palms facing up. The face is lowered and the legs are spread as far as they can go. When a prisoner assumes a stress position, it is easy to beat him. They beat the back of the head and the temples but not with a fist but with an open hand in order not to leave a mark. They beat me with their feet but not with the toe of their boots but with the flats of their soles on my body, on my feet, on the inner parts of the thigh where the groin is. When I tried to cover myself with my hands they beat me on my hands too. There was a bruise on my elbow which took about a month to heal. There were also bruises on my inner thighs. They beat you until you fall down. When you get up they beat you again until you agree with what they are telling you. They tell you, for example, "You are worthless, you are a faggot" and you need to answer, "I am worthless, I am a faggot". They forced me to say "Putin is our president".

[…]

Moscow functionaries arrived November 2 and visited the prison colony again on November 3. When I told them that I am forced to share a cell with a person who is mentally ill, the administration of the prison colony said, "it is for his own safety." Then I spoke to the local members of a state sponsored human rights monitoring commission (ОНК) I got the impression that their leadership was close friends with the prison officials, but I still told them everything. I did not even realize that I had a seizure during my conversation with them. When I was talking I felt that I was swaying back and forth and that I could stop. Then at some point my breathing stopped. I could not inhale or exhale and I felt that I was falling into darkness. Nobody told me about the convulsions or the foam in my mouth, I only dimly felt, as if through fog, that I am being carried and undressed and then I felt an injection in my buttocks. My teeth hurt too probably because they were forced apart to prevent me from biting my tongue.

[...]

The next day they took me someplace without telling me where. I saw a beautiful lake through the window of the police van. They took an X-ray of my head and then drove me back to the prison without showing me the results. If I had known that they were taking me to the hospital, I would have asked them to look at my heart because lately I have been feeling pain in my chest.

Now they do not beat me anymore but they continue to mock me. For example, "You really needed to complain, didn't you. You achieved nothing and only made yourself into a faggot in the eyes of the world. You will save no one."

Zotova, Anastasia, comp. "'Никого ты не спасешь' Рассказ Ильдара Дадина о том, что происходило с ним в ИК-7 — до и после его письма о пытках” [‘You will save no one’ Ildar speaks about what happened to him in IK-7 before and after his letter about torture]. Meduza. N.p., 11 Nov. 2016. Web. 11 Nov. 2016. <https://meduza.io/feature/2016/11/11/nikogo-ty-ne-spasesh>.

02.26.17

During the torture, when they put my hands behind my back and handcuffed me and hung me up so that my shoulders were twisted and the handcuffs cut my writs, I felt pain, and when, at the same time, they said that a person was about to rape me, I remember that in the second minute I broke. I was ready to say anything to make the pain stop. After fifteen minutes I thought, am I ready to give up something most precious in order to stop the pain? Like in Orwell, either my mother, torture her and not me, or like under Stalin, denounce the others. If they demand, “Denounce your mother or denounce your wife, and we will stop torturing you,” how would I answer? Even now I do not remember exactly, but I think I answered yes, I was ready to sign anything to escape the torture. Torture them, kill them and not me. And two or three days after that, when I felt that I was completely morally broken and felt that I was ready, possibly, to give my wife to those executioners so that I would not feel this pain myself, I was so devastated that I did not even want to live, and I thought that if I should be released, the first thing I would do would be to leave Russia, because here the people who fight with injustice, the only thing that they have left is to be taken by these sadistic executioners, there are no more legal means of resistance. I felt that way then.

But after some time…I will digress. I think that the most important thing is not that a person can fall but the ability of a person to find strength in one’s self to rise and stand up again. I read a book of Buddhist monks, The Book of Life and Death, I forgot what it is called, The Book of the Dead, something like that.2 I remembered it all again, how I was subjected to torture, and I realized that it is better that I be subjected to this than, God forbid, my wife or my mother or any of my friends. It is better that I be tortured, I am able, I am a man, rather than they. And because of that…not just because of that, after I heard the other people being beaten, I understood plain and clear that if I have the chance to leave, and they don’t have the chance to leave, and I think that all people have equal rights then why do I have to leave and they have to stay? They will be tortured. I cannot explain this. I realized that if others are being tortured, then I cannot leave until I see that they are not being tortured or that they can leave just like me. After that I realized clearly that I am ready to be hung again by the handcuffs and to face other torture. I will probably break again, but at least I am ready to fight back. While they are also being tortured, how will I leave? My conscience will not let me live if I know that people are being tortured there and I left. Am I somehow better than them? I don’t think that I am better than them even if it is possible that among them are murders, criminals, and thieves. But the ones who are torturing are even worse than the ones that they torture.

2. Ildar is referring to the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the Western name for a selection of passages from the Bardo Thödol, a foundational text of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism.

Освобождение Ильдара Дадина [The Release of Ildar Dadin]. Telekanal Dozhd. 26 Feb. 2017. Facebook Live. Web. 26 Feb. 2017.

<https://www.facebook.com/tvrain/videos/10154652269923800/?pnref=story>.

02.27.17

In the second minute I say, “I agree to everything,” hinting that they should stop. After fifteen minutes I prayed that they would come faster. I heard someone walking with keys and it seemed, if only he would come to me… Maybe they know that a person is suffering, waiting, and hearing the keys and they will finally take off the handcuffs and this pain will stop.

[…]

I began to feel that there is not enough air. I started to panic. But then I got used to it. I just understood that if I quickly inhale and exhale with shallow breaths then it is possible to breathe. When I am nervous, this started after IK-73, after the attack which happened on November 2nd. I realized later that I begin to stutter when I am nervous, when I am not nervous I speak quietly and well. Now I will try to speak calmly.

The first three days after the torture I had a wish: those beds nailed to the floor have tables with iron corners. When I did not know how one day, it was so hard, morally and physically, a second day, a third day, I was ready to die, that was not so terrifying. But I did not know how to stop this constant suffering. The only way out I saw for myself was to take my own life. Just to hit my temple on the edge of the iron corner so that I would die. Not a hunger strike. A hunger strike was ridiculous to me. The choice then was to live or not to live. If not to live, then to take my life, that is all, because at that time I did not feel myself to be a human being.

3. Corrective Labor Colony No. 7, the prison camp in Karelia to which Ildar was transferred in September 2016.

Ильдар Дадин: «На второй минуте пыток я сломался» [Ildar Dadin: "In the Second Minute of Torture I broke"]. Telekanal Dozhd. 27 Feb. 2017. Web. 28 Feb. 2017. <https://tvrain.ru/teleshow/here_and_now/dadin_interview-428595/>.

Ilya

09.06.16

Ariella: My first question is what made you engage in political activity.

Ilya: Right back at you. What do you consider to be political activity? For example, there used to be and still is, thankfully, a television channel called 2x2 which was, in part, owned by Gazprom. It showed really awesome cartoons and films. I loved it. In the late 2000s we organized rallies in its defense, collected signatures and other things. Is this political activity or not or is it just a cartoon channel?

Ariella: I think yes.

Ilya: Well then the fact that they wanted to take away 2x2 moved me to act. In Russia, there is very little to watch on TV: some interesting news, 2x2, and sports. That is it. And they wanted to take the most fun cartoons away.

[….]

Ariella: What is your favorite cartoon on the channel?

Ilya: The Simpsons.

Ariella: The Simpsons? So they even broadcast the Simpsons?

Ilya: Of course. The Simpsons, South Park, later in the night more hardcore, violent ones. [….]

Ariella: How did you stop them from closing it?

Ilya: We held rallies, made a lot of noise through the media – we let them know that some are not indifferent to this channel, and that we will not let them take it away just like that.

Ariella: You organized in the streets?

Ilya: Yeah, we collected signatures, organized some small rallies and protests. We even stood with a banner at a football field.

Ariella: What did the banner say?

Ilya: “Save the Simpsons”. With Homer and Marge on the sides. We were the only football club, I think, that made a banner about the closing of 2x2.

Ariella: And then what?

Ilya: Well actually, I only became politically active in 2011 when under tragic circumstances my college and football life ended. On the one hand, things in the country were coming to a boil a bit, and it began to come to the surface, and people began to come together about political questions, and on the other, damn it, they closed my football club and my school. I was bored and had nothing to do and then I saw they had banners, flags, pyrotechnics, problems with cops. They just don’t play football, otherwise it’s practically the same thing.

[….]

Ilya: I don’t know how to say it in a way that is appropriate.

Ariella: In prison, you can’t have sex?

Ilya: No, there is [sex]. You can even hire a prostitute.

Ariella: Seriously? Even in prison?

Ilya: You see, the thing is that, as you might have noticed in Russia, institutions have crumbled, police, courts, civic institutions, they just do not work. That is all. Corruption everywhere. In prison, it is the same. The system of punishment during the Soviet times… they went hard, but now if you have money and brains you can pull through. For fifteen thousand I think, let’s say you pay fifteen grand, they take you to an exercise yard with a woman, also a prisoner who works in maintenance. There are prisoners who after having been convicted, sign some papers, and, instead of being sent to a labor colony, stay in the prison and help cook, clean, and do those kinds of things. Technically, the guards can refuse, they aren’t supposed to allow it, but they take some for themselves and let you in for an hour or two to the exercise yard, it’s like a cell without a roof.

[…]

Ariella: Did you buy or hire a prostitute?

Ilya: I am too young, why do I need prostitutes? No, no. You deprive yourself of a lot in prison, including this.

[….]

Everyone. It doesn’t matter how I feel about a person or what I think of them good or bad, a person needs certain basic functions….how do you say it? The basic comfort of being able to sleep and eat normally, to go to the bathroom and to brush teeth, a person needs to have it; it cannot be taken away. You can control his life, make him get up at six and go to sleep at ten, don’t sleep during the day, make him do something else. Prison conditions depend on the location, they can be different still a person needs a pencil, paper, toothbrush, bread, water. Because in prison, sometimes there even isn’t enough bread, it is so bad.

[….]

Ariella: Do you consider your political activity to be an act of love?

Ilya: Well, honestly, I consider my political activity my job. I have always tried to separate my personal life from my work life and so this is not an act of love but more an act of help. And help to lots of very different people. Yesterday, I could send packages to a shelter for

single mothers in Chelyabinsk who have been recently released from labor colonies and today I will go to Lefortovo to bring to bring more packages to girls from Dagestan who have been imprisoned for supporting Islamic terrorism. I don’t have sympathy for the last group at all; I have opposite views from them, but, at the same time, I don’t feel uncomfortable when I send something to them because I don’t include the personal. First of all, work assumes that you remove the personal a little, and second, it does not matter who is in prison, a person should be able to live normally in prison, so that he does not lose human form - that is convenient for the prison administration and for the gangs, because animals are easier to control.

Nikolai

09.07.16

Ariella: Was there some specific event or a feeling that made you think about [politics]? Nikolai: Probably, I can only guess, perhaps, it was the events of the GKChP. Ariella: What was the GKChP? Please tell me.

Nikolai: I was four or five, I don't remember exactly, when I went with my parents and some other kids to the woods to play. It was not far from the house where I lived but it was outside of Moscow even though I lived in Moscow then. No, no, that is not it. Then there was only talk of the GKChP. In my childhood - that is why I started telling you about the forest - it all became one event in my mind GKChP and what happened in '93, when there was a conflict between the supporters of Yeltsin and those who opposed him. And now, because I was little, it all came together in my mind as one event.

Then, in the forest, as I began telling you, I heard shots being fired from some sort of heavy guns, even though it was outside of Moscow, there you could still hear it. Maybe that influenced my interest. I saw all kinds of reports on T.V, so maybe that influenced my interest in politics, or maybe not. I can't speak with certainty.

Ariella: And what is the GKChP?

Nikolai: GKChP is the Government Committee on the State of Emergency. Then, a number of reactionary and conservative politicians who wanted to preserve the old Soviet Union and the old conservative Soviet order, decided to execute a government coup, deposed Boris Yeltsin, the president of the USSR, and introduced its own GKChP, a state of emergency. They started to bring tanks into Moscow.

Ariella: You were little. Did you see the tanks?

Nikolai: I saw them on T. V. Although my parents told me that my mother worked at a government radio station and that an armored personnel carrier came to the building where she was working, and pointed a gun at one of the windows.

Ariella: Where did she work?

Nikolai: At the radio, the government radio.

Ariella: What do you mean that they pointed it?

Nikolai: They didn't shoot, the gun just stood there. They did not have ammunition actually, the soldiers who stormed Moscow.

Ariella: So there was no fighting, they were just showing off their power.

Nikolai: It is possible. But when she was telling me this, it was 25 years ago, when she was telling me, so I can't promise accuracy. This is how I remember it.

Ariella: How old were you when she told you this?

Nikolai: Four or five, I don't remember exactly. August of '91 - so I must have been four years old.

Ariella: What did you think about it then?

Nikolai: My parents blamed it all on me. They said that it is because you are behaving badly that the war is starting. And I thought to myself how could me behaving badly have anything to do with the war?

Ariella: So you already saw through their logic.

Nikolai: Yes.

Olga R.

09.12.2016

Ariella: When your husband was in prison, how did it affect your relationship? How did you visit him?

Olga: It had a good effect on our relationship. I think that it weren’t for prison we would have gotten divorced.

Ariella: Why?

Olga: Because prison is like a filter in photographs. You choose a filter and details that you had no seen before light up. You can put them in the foreground, and remove what is unnecessary. Prison is a good filter. If you have a good shot, you can do a lot with it, you see? If you choose the wrong filter or the wrong shot, everything is blurred, and the person is blurred. But if everything is chosen right, you look and think, “Wow what a person. So this is my husband? Well girls.” Of course this did not become clear right away, but it happened pretty quickly, let’s say in the first year. And, of course, I already saw a different person and this was very, very interesting, fascinating, and it gave me pleasure that this inmate is my husband.

Ariella: What aspects of his character did you see through this prison filter that you had not seen in him before?

Olga: First of all, I discovered a person who is strong, which I was not expecting because he is from an old, spoiled, family. A prominent family. All of a sudden I saw a very strong person. A person ready to undergo hardship, ready to suffer deprivation of food, freedom, hygiene, everything. A person ready to fight back against gang members and absolutely not ready to inform on someone. They asked him to testify many times. An absolutely uncompromising person. A person who can find common ground with any social class, with any person at all. He made friends with a homeless man. He made friends and we are still friends with a simple guy he had met there, an electric, a very good guy. I really liked what I saw. I stood everything without fear. It gives comfort when you stand back to back and you believe the back that it is behind you.

Ariella: And the back was…

Olga: Yes. It was secure, the back was.

Ariella: And the back of your husband?

Olga: Yes, back to back. I made a lot of abrupt moves like he did, and if his back had not been there, it would have been bad.

Ariella: So without him it would have been bad for you.

Olga: No, if one had faltered it would have all crashed down. If I had faltered, he would have been hurt. If he had faltered, I would have been hurt. But we held on somehow.

Ariella: Do you feel, I will use these words and then I can rephrase it, conflict or harmony between your sense of responsibility for your husband, desire that he not be in prison, and loyalty to your political ideals that can put you or your husband in danger?

Olga: Yes, of course there are a lot of conflicts here. He was imprisoned twice, you know. Once he was imprisoned for his own actions, and the second time, really, he was imprisoned because of me. And of course, I felt, to say the least, embarrassed in front of him, that he is going to prison. And a lot of years have passed and he has never blamed me, not even once, and when we talk about it, especially with other people, he says and I say that the first time he was imprisoned for himself and the second time he was imprisoned for me and my actions. And let’s skip ahead. When 2011 happened, the year of protests and 2012, he was already free at that time and we talked together when all the protests started that we won’t get involved with them. We’re not going to go anywhere, no activism. We talked about it the whole evening and in the morning we got in the car to go to Zvenigorod to get away and he was behind the wheel and I was next to him, we didn’t talk at all, and we went in the other direction. We didn’t say a word to each other. We had been talking to each other the whole day that there we were not going to go. And then in the morning we got in the car and went. We didn’t need to talk about it; we just went to the protest.

And I became the sponsor of the opposition because Sergei Parkhomenko4 called my husband and said, “You are a financier. I know that you can go to prison now. Let Olga make an account.” They agreed and told me about it as a done deal. They are going to make an account and I am going to manage it. And I said, “What?” We drove, we drove, we drove, and [I said] “OK, of course. Good. I will do it.” So we didn’t have any conflicts about this. He knew perfectly what he was risking. And I knew what he was risking. I don’t think that we talked about it explicitly but we decided that if we go to prison, we go to prison. And when it became clear that they would send him to prison and I was preparing ways to get him out of Russia, it was clear that he was getting pushed out, he drew me a table and said, “Here are the pros and cons if I leave and the pros and cons if I stay. You see, it is clear.” “OK, go to prison.” Then I told him that I wouldn’t be able to handle it a second time. The second time, I will do nothing. I can’t do it anymore. I know what I am dealing with. “OK. You don’t have to.” Of course, I was not going to go anywhere. So of course, there were always conflicts. We felt them all the time. We feel them. They are always present.

Later, when he got out he said that Russia Behind Bars5 is good, but I don’t want you to go to prisons all the time. And I said, “That is not even a question, of course, I am going to visit prisons.” “OK, let’s go together. “

We agree that we probably should not be doing this. And then we do it together.

4. Sergei Parkhomenko is a Moscow journalist and political commentator who was active in the 2011-2013 protest movement.

5. Russia Behind Bars (Russian: Русь Сидящая) is a Moscow based non-profit which provides material and legal aid to prisoners. Olga began the organization after her husband was imprisoned for the first time in 2008.

Olga S.

09.09.2016

Ariella: Tell me a little bit about yourself.

Olga: I don't know. Well, I am a teacher, I teach digital design. I have two children, both are already grown up. I don't know. I don't know how to talk about myself, that is for sure. I don't know what interests another person. I don't know how and I don't like to talk about myself because I am an ordinary woman, a statistically average teacher who lived an ordinary Soviet life and Perestroika and now I live in this capitalist Russia, yes? I am a statistically average person. My life, properly speaking, passed the same way as the lives of other women who are my age.

Sergei

09.20.16

Ariella: My first question is, 'How are things going for you today?'

Sergei: You ask me," How are things going?" So I got out of prison two months ago now. So I have not found a job yet but I am looking. And an important question, moment - my wife says that if you are planning to continue all this, then just live by yourself. That is, I am getting evicted.

Ariella: To continue what?

Sergei: Well, to continue to be involved in the opposition. For example to go to a protest, that is it. It is like a red cloth for a bull. That is, she immediately begins not to become hysterical but close to it. So she really does not like all this. She is a cowardly person. She is afraid. For example, I went to the polls and she said, “If you go to the polls as an observer then by that time you should have already moved out.”

Ariella: Did she always react this way to your political activities or did prison change her?

Sergei: Of course prison changed her. She didn't know it was so serious before. I would go to demonstrations and she called it having fun, that I just go to have fun. I, myself, didn't think that I would get arrested and go to prison. Well, I knew that I would get arrested, of course, I was arrested many times - about going to prison I knew that it was possible. You see, it's one thing to understand that something is possible, you can go out and get run over by a car, we all know this, but when it happens it is already something completely different, right?

[...]

Ariella: Maybe you answered the question already, but do you consider your public work an act of love?

Sergei: I am telling you, I am not a specialist with regard to love. Love is a very broad concept. It can be towards children or towards a person or towards an idea etc. Well in this case, if it is love of freedom then I understand but if under an act of love you mean relations towards a person, as it is usually understood, then [pause] I don't know.

Though, in this case, it is still a question of freedom. About rights, about freedom. About love of people, I don't know. That is something you would know more about.

Ariella: What is the relationship or conflict between the love for a person, as you said, and the love of freedom?

Sergei: Conflict?

Ariella: Or harmony.

Sergei: No well, complete freedom is practically unattainable, first off, because a person lives in a community and in this community live people whom he loves and, consequently, they can and certainly do have interests and desires which contradict the interests of this person and his freedom and so, naturally, a person -- he can and he should somehow limit himself. For example, if someone he loves tells him, “I do not allow you, do not go to such and such a place,” then this is a kind of limit on his freedom and that is somehow not OK. But if he, himself, understanding that another person does not need this and does not want this then places limits on himself then that is a whole different story. Just like if I am called an idiot then my feelings will be hurt, but if I call myself an idiot then I will not be hurt -- I have a right, you understand. So, there has to be some sort of inner culture, some sort of inner balance of interests, so a person understands that he does not live alone, that he lives in society and that everyone has their own interests and, in the ideal, life should be set up in such a way that he understands that he is not the most important person and that everyone does not have to yield to his interests, but there should be such an arrangement so as to maximally satisfy everyone.

[...]

Ariella: Do you think that friendship and love can play some sort of role in freeing Russia? Sergei: Well, you see, this is not a very direct question, or, to be more precise, answer.

You can say yes, but it would be such distant connections that ... In principle, with regards to freeing Russia practically everything plays a role, right? Including friendship and love. For example, a person lives, especially an adult, he does not live, does he, for himself. To live for himself is not interesting. When he lives alone then it seems that nothing is necessary because parents live for their children, right? Or for their own parents. My Mother, for example, is a senior citizen, my children go to school and I perfectly understand that they live in this country and all the bad things that are happening here are reflected just the same on them.

[...]

Ariella: So you are saying that everyone lives for someone else, for another person. Sergei: Yes.

Ariella: Then what do you live for?

[Long pause]

Sergei: Well, that's a philosophical question you know. That is just like...I will give an example. We told our son: A butterfly -- somebody ate it, a worm, something else, so everything in nature is needed for something. For example, mosquitoes seem to be needed for nothing, but the birds feed on them and other things. We told him this and one wonderful moment he said, "This thing is needed for that." I was so surprised at him. So he had absorbed these conversations -- what we had told him. “So everything is needed for something,” I said. "Of course." "Then explain to me why nature needs Krivov Vasily," that is his name.

He was silent. "So think about it," I said. A few days pass, even a week, he didn't forget somehow, I feel it. He comes up to me and says I was thinking and thinking and I couldn't understand why I am needed. Well, I couldn't explain it to him. But in general a person lives, somehow, so that in the process of his life, he makes the world better.