The essay below accompanies the selection of poems by Samuel B. Greenberg which also appears in this issue of Mouse.

* * *

Repeat experience has taught me: when I am convinced there is nothing new under the sun, the place to look is underground. After all I know there are still those—forgotten or neglected—who have yet to be unearthed, studied, reexamined, recirculated. For every well-burnished household name whose works are brought out in their umpteenth printings and deluxe centennial editions, there are a handful—just as worthy, on their merits—whose works are scattered across little magazines and small-press limited-printings, or whose unpublished manuscripts abide in archival boxes (if they’re lucky) or molder in attics (if they’re not).

Samuel B. Greenberg is one of these overlooked, if relatively lucky, makers whose life’s work is housed in a major university collection but whose writings have garnered only occasional notice and have yet to be made available to readers in anywhere near a complete or editorially stable form. What does exist is either scarce, fractional, or misrepresentative—but in spite of it highly original and suggestive. As a sickly decadent romantic he bears comparison to John Keats, as youthful visionary to Arthur Rimbaud, as hermetic eccentric to Emily Dickinson—and he is a talent worthy of their company, which is to say like these too there has never been a poet like Greenberg. He bears out the Surrealists’ suspicion that their favorite injunction of Lautréamont’s—that “Poetry must be made by all”—would tend to break their way. He should excite eclectic readers, with a classical appreciation and yet a taste for strangeness. But too he is a poet’s poet, his is the kind of poetry which stirs one to write poetry, his inspiration so pure and intoxicating that I have often put down his poems only to have line after new line spring up spontaneous in my inner ear.

The time is therefore overdue for a comprehensive edition of his poetry which would re-edit and recirculate the slim and scattered offerings heretofore available as well as tackle the great majority of his writings that have never been published. The selection of poems and other writings by Samuel B. Greenberg published elsewhere in this issue of Mouse represent a first fraction of my own ongoing editorial work on his papers in the Fales Manuscript Collection at New York University. Here I will supplement that work with a sketch of Greenberg’s life and circumstances, his poetry, and a résumé of his publication history to date.

* * *

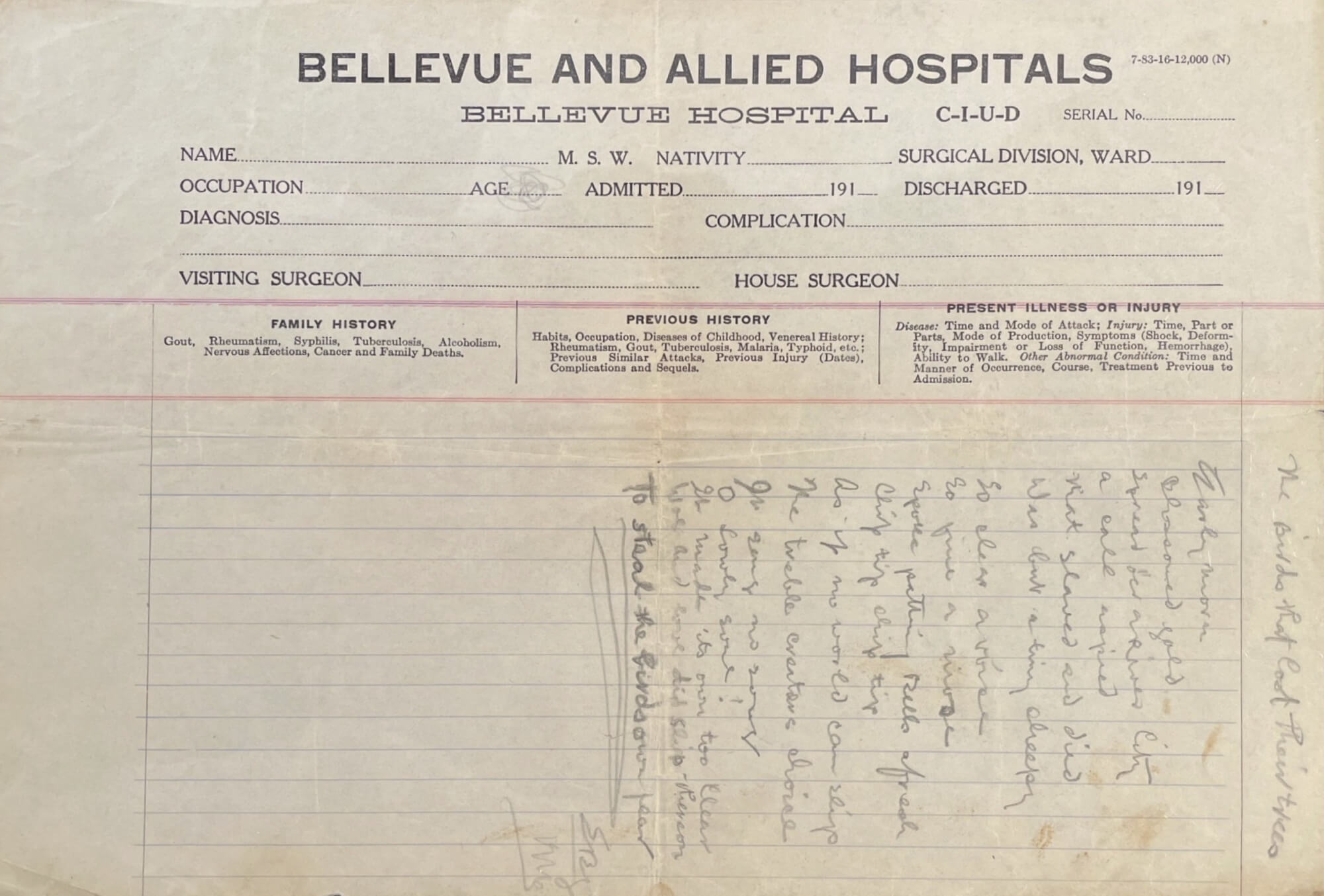

Samuel Bernard Greenberg was born in 1893 in Austria, and emigrated with his family to New York in 1900, where they lived on the Lower East Side. He attended public school until he was 14, when he left school to work, first at embroidering with his father and later at his brother’s leather bag manufactory; the working conditions at the latter may have contributed to his contracting the tuberculosis that would eventually kill him. His first hospitalization was in 1912, at the age of 18, and for the rest of his life he would be in and out of hospitals, returning to work when he was well enough, until a final stay at the Manhattan State Hospital on Ward’s Island in 1917. He died August 16, 1917, only 23 years old.

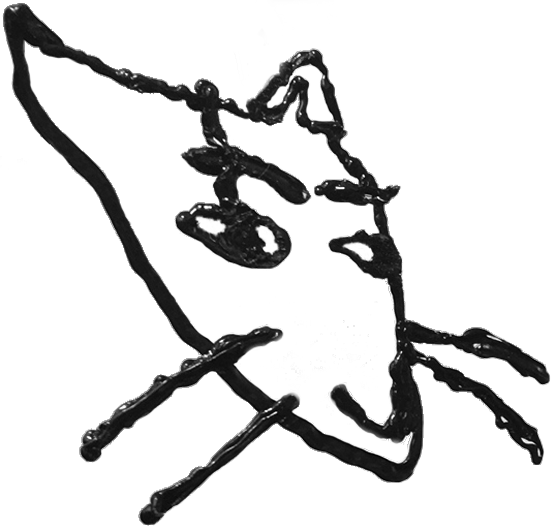

At that time, the primary prescriptions for tuberculosis were confinement to a sanatorium, and rest. Greenberg’s still-youthful and clearly highly-active mind reacted to this rest-cure by seeking compatible outlets, and happily, he hit on poetry. In an extreme burst of creativity beginning around 1913 and tapering only in his final months (a period of hardly four years in all) Samuel Greenberg scribbled into at least a dozen notebooks plus myriad and multifarious scraps of paper some 600 poems, several plays, and diverse jottings and sketches. To inform his writing, he supplemented his incomplete public school education with voracious reading at the public library as well as (according to friends’ recollections) from the dictionary, visits to the Metropolitan Museum and classical music concerts, and intellectual and aesthetic conversation with a coterie of acquaintances he met through his brother’s music teacher (“fellow men of the dime novel nobility” as Greenberg called them in an autobiographical prose piece). Consequently his poetry exhibits an uneven surface of poetic imitations and archaicisms, obscure words and idiosyncratic usages, misspellings and neologisms, a wavering commitment to meter and rhyme, and an overall pureness of inspiration and originality of expression which has made him a (very occasional) cause célèbre among later modernist and experimental poets. As the poet Charles Bernstein characterizes it: “a wild, sound-wracked, syntactic syncretism that verges on the abstract and the rhapsodic”.

These are the writings—the sum of a brief but beautiful life prostrated to poetry—which are housed in the Fales Manuscript Collection as part of the special collections at NYU. And despite their merits and 100 years of percolation, they have never seen publication in their entirety, nor anything approaching it.

Nor was anything published in his lifetime, and the handful of significant posthumous surfacings have all been problematic to some degree. The first in fact is a matter of small literary-historical infamy. A modernist poet destined for much greater renown than Greenberg, Hart Crane, while still early in his writing career, made the acquaintance of Greenberg’s former friend and mentor, William Murrell Fisher, who was at that time custodian of a portion of his manuscripts. Hart Crane was enthralled—“a Rimbaud in embryo” went his epithet for Greenberg in an excited letter to a friend—and borrowed them from Fisher to make his own typed copies. From these he subsequently borrowed and adapted lines, phrases, and images to use in some of his own formative poetry. Whether this constitutes outright plagiarism (the use was not acknowledged explicitly or publicly by Crane and had to wait for biographers and scholars to unearth) or the kind of sampling, homage, or imitation which constitute many a poet’s work especially in their early writing, has been debated by scholars and editors of both figures.

The next appearance of Greenberg’s poetry, in 1939 (this time a bona fide publication under his own name), goes further in securing for Greenberg the aura of a homegrown self-modernizer slipped through the cracks. Just three years into running his canon-making New Directions publishing outfit, James Laughlin put out a slim pamphlet of Poems from the Greenberg Manuscripts, a small but significant selection of poems with an essay by the editor which, while occasionally backhanded in its praise, does affirm the “strange but remarkable talent” on display in them. Publication in New Directions thereby put Greenberg’s name in proximity to those of Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, and other major literary experimenters. A version of this pamphlet was since reissued from New Directions in 2019 in a somewhat expanded selection under the supervision of poet and editor Garrett Caples.

The most (quantitatively) generous print publication of Greenberg’s poetry to date remains Poems by Samuel Greenberg from Henry Holt and Company in 1947, edited by Harold Holden and Jack McManis. Unfortunately, its editors saw fit to give Greenberg what we might call the “Emily Dickinson treatment”, which is when an idiosyncratic, experimental, ahead-of-their-time poet is handled by aesthetically conservative editors who seek to “regularize” the poet’s work to read more like “acceptable” poetry. Wholesale deletions of lines, substitutions of words, intrusive repunctuation, and (albeit unintentional) misreadings of handwriting are all rife in the book. Too, their editorial introduction occasionally lapses into patronizing, even moreso the preface by renowned poetry arch-conservative Allen Tate. Thus the most substantial book publication of Greenberg is also the least trustworthy—taken with that grain of salt, however, the sincere and perspicacious admirer of Greenberg will find that his unmistakable genius shines through it still.

The final substantial publication of Greenberg’s work is not in print. Of course, none of the foregoing are still “in print”, but this was never printed in the first place. Instead, it is hosted on a website of strange URL: logopoeia.com/greenberg. Created by Michael Smith in 2000, it is simultaneously the most widely accessible and the most fidelitous to the originals which has yet been published. It, too, is only a selection however. Also, while the connection of the works included on the site to their manuscript originals is evident, it is nowhere made explicit. No obvious critical apparatus or citational practice is included, nor much of an editorial statement or introduction.

Moreover, to the extent that they are derived from the manuscripts, the presentation of the poems on logopoeia.com/greenberg if anything skews too-faithful. The otherwise noble desire to preserve an original creative impulse—especially in the case of an “outsider artist”—can obscure the fact that a manuscript draft of a poem is still just that: a draft. Occasionally a misspelling is just a slip of the pen. Additionally, a too-precious regard for manuscripts runs the risk of seeing quirks of an individual’s handwriting as being necessarily intentional or meaningful qua poetry. A sharp eye (and especially one familiar with the originals) will note that many of the mid-line or even mid-word capitalizations on the logopoeia site are of the letters “B” or “H” (thus such typographic oddities as “slumBer” or “sHadows”). But just because Greenberg’s habitual penmanship often renders these letters with forms resembling the capitals, it does not necessarily follow that a grammatical or poetically significant “capitalization” is implied or intended (in this way Greenberg is not an Emily Dickinson). The results of this well-intentioned but ultimately misguided attempt to facsimilize a manuscript in a typed version are in my opinion more often distracting than illuminating, and serve less to bring the aura of the original closer than to keep the actual poetry further away for a casual reader.

It’s not inconceivable that had Greenberg been able to see his work into print during his life—a desire he is attested to have expressed—that he would have welcomed the relationship with an editor and an opportunity to correct or improve his spelling and grammar (without having to go so far as Holden and McManis in meddling). After all, Greenberg laments in his prose autobiography, after relating the fact of his hospitalization, “Where was school? O what I would give for the knowledge of grammatic truth!”

* * *

In this issue of Mouse I have offered a new selection of poems by Samuel Greenberg. With a few exceptions (addressed below), they have not been published in any of the publications discussed above; all have been transcribed and edited from his original manuscripts. I have attempted on the one hand to present them in all of the idiosyncratic, pure inspiration to which their interest and astonishment is owed—I have endeavored to treat him not as an untutored outsider of only sporadic genius, a diamond in the rough, but as a serious poet on his own merits. On the other hand, I wanted to present his poetry in the best light, which to my mind includes the small but appreciable benefits that come of light editing. To this end capitalization has been regularized, obvious and distracting errors in spelling (except when they seemed intentional, productive, or meaningful) have been corrected, occasionally punctuation has been supplied when clarity or legibility wanted it, and in rarer cases a given word represents my best guess at a handwritten one which I have been unable to decipher with absolute certainty. It is my opinion that these small changes make Greenberg the more readable and approachable for all comers, lend a dignity to his poems which after all he wanted and they deserve, without doing violence to his original expression.

A thematic narrative has been loosely followed in their selection and arrangement. “Motives”, “Literature Listener”, and “An Ode to a Trio” suggest the self-declaration and formation of the poet, and the sources of his inspiration. “Beauty” elliptically sketches an aesthetics or poetics. “Delicious Fruit” and “Butterfly” exhibit the lighter side of his inspiration, derived from nature; “Man”, “Eye Borrows Eye”, and “Dark Images” the darker side, touching on human conditions. From “The Thorax”, with its repeating pulmonary refrains, the poet’s illness looms in the background, gathering in poignancy through the final selections, as the poet’s sense of mortality and his poetic abilities wax in inverse proportion to his waning health.

Versions of “Motives”, “Man”, “Dark Images”, and the “Sonnet to Death” were published in the book edited by Holden and McManis, but their republication here reverses some of those editors’ least forgivable interventions. Their take on “Motives” for instance utterly changes the line “and the windy flurs by chance” to “And the windy flurries that sing—”, stupidly altering the sense to insert another rhyme not there in the original. In “Man” they mistakenly give “mind” for “mine!” in the fourth line, a misreading which might be understandable given the handwriting crammed to the edge of the page in the manuscript, except that the following sentence “Quite true, we dug gold out / Of thee” makes the intended word rather obvious. They also remove the two most adventurous (they must have thought “troublesome” or “inconvenient”) lines, the second and the tenth. Another avoidable misreading, when read in context, appears in Holden and McManis’s version of “Sonnet to Death” (titled simply “Death” in their version, for reasons which will become clear) where they have the line “Thus makest thou us untrained a blend!” while the final word obviously reads “beast” in the original and thus makes the more sense with “untrained”. Less understandable (frankly astonishing) they transform the traditionally 14-line “Sonnet to Death” into the 11-line poem “Death”, ending at the just-quoted, mis-read line and thereby suppressing the incredible final couplet. “Dark Images” is less egregiously treated but still plagued with small unnecessary supplements of punctuation, the making of “ever” into “every”, and the deletion of one of Greenberg’s favorite obscurities, “ween”, at the end of the penultimate line.

I will otherwise leave the poems to speak for themselves—and for us, as I feel certain they are capable of doing even a century on. As one of Greenberg’s occasional champions, American beatnik-Surrealist poet Philip Lamantia, notes, both because and in spite of their expression in a kind of “‘romantic’ idiom”, his poems “doubly [offer] us a glimpse of what is missing in late nineteenth century poetry in America, and [gift] us with a view of perturbation and irrepressibility revealing the human condition”. Such perturbation and irrepressibility should be a welcome discovery for one who judges like Emily Dickinson: “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry”, and who feels in parallel that much of what passes for poetry leaves one's cranium firmly screwed-on. While already the 21st century is older than Greenberg lived to be, he still offers that glimpse—he himself still is—what is missing from our poetry.