First, I would like you to meet my father-in-law. I see him many times a day, which isn’t as odd as it sounds, because he lives in my basement. Not my cellar, mind you, like Kaspar Hauser or something. The basement has windows, though my in-laws keep their blinds down.

It’s 8 a.m. and I’ve just sat down to write in my kitchen when I hear a familiar shuffle—the sound of my father in-law coming up the stairs. It’s only eight carpeted steps but it will take him some time. I used to go to him to see what he wanted, in an attempt to save him the labor of coming upstairs, until I realized I was merely short-circuiting a well-planned routine: He’d come up anyway and act as if my interruption on the stairs was proof I’d missed some stage directions, a miscue best ignored. His laugh suggests I should get it right next time.

I know when I hear him coming, I still have time to get my coffee or make eggs or whatever. Soon enough, he’ll complete his journey and address me. When he arrives, he looks at me and begins with a laugh that is hearty for a small, ninety-two-year-old South Indian man. He’s never about to tell me a joke. The laugh is a signal. It says, “I come with goodwill.” In years past, he might very well not have come with goodwill. Maybe he’d be mad or have something he considered very serious to discuss. But now, however, he is almost certainly here to say one word to me:

“Apples?”

A one-word question with only one correct answer: “Yes, please!” This will get him to laugh again and then shuffle off back downstairs to fetch a small bowl of cut apples and bring them to me. We all eat a lot of apples in my house now.

If he’s not on the apple odyssey, he’s coming to see who is in the kitchen, then calculate who is missing, and ask after them. “Where is Suni?” he’ll ask if my wife is not there. I will say she is upstairs, to which he’ll respond, “She is out?” I will say, “No, she’s upstairs” and he’ll say, “OK, she is out.” I don’t know if he asks about me when I’m not there. He probably does. He’ll then shuffle off to the front door and check on the conditions. He’s mainly interested to know if the gate is closed and whether the trash has been picked up. Depending on the facts, he’ll go out to close the gate or drag the garbage can back inside. Once in a while, the can will be missing and he’ll come back very alarmed. He’ll laugh, of course, but wax very serious and tell me that “Someone has made off with our rubbish bin!” Then he will stand there and wait by my side, a little like a cat expecting something, until I go out and find it.

The third and last possible mission for his visit is simply to hand out a little piece of chocolate to whoever is around. It is always one square from a Trader Joe’s one-pound bar of milk chocolate. Many of my friends have been recipients. If there are unaccounted-for visitors upstairs, as is often the case, he returns with more. My friends smile at this more than the members of my family who, at this point, see it more as a duty than dessert.

These are the activities that define the scope of my father-in-law’s late life. I’ve been around long enough to see the transition into this smaller, trinitarian being. I initially viewed it as somewhat tragic, but I’ve now grown to really love this new man and his routines. I see him as the lovely remainder of what used to be more—but not necessarily better or happier. Now he lives a life of service and mirth. He’s the laughing Apple Wala. He is the Minder of the Garbage Cans. A Chocolate Santa. All very old people transform, but this is the first time I’ve seen it up so close. It’s not a Kafkaesque transformation; he’s not so much Gregor Samsa as one of the fantastical creatures on a planet the Little Prince visited before finding the saddest of all places, the Earth.

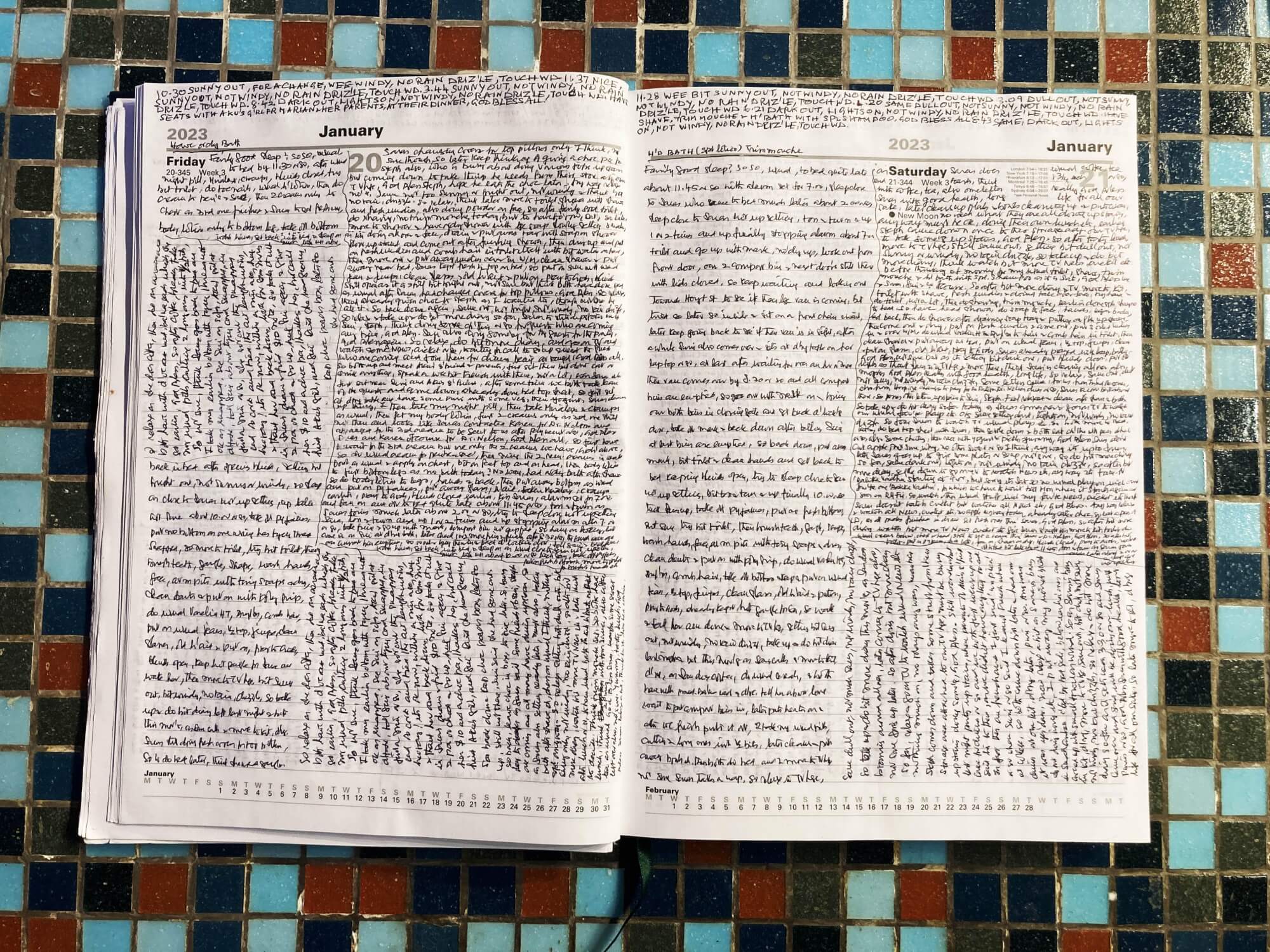

I met my father-in-law when he was in his seventies, a civil engineer working for the British Government in their department of building permits. He did his job entirely by the book, of that I’m sure. I suspect he was born a bureaucrat. He’s kept a meticulous record of his daily activities for at least sixty years now. He’s filled many dozens of diaries, all kept in a box downstairs. Every single spot on every page is filled with words, giving the impression of the view of farmland from a plane: Each entry is a different geometric shape filling in some previously unused space. He writes in a tiny hand no one else can read. On a few occasions when someone has wanted to know about a particular day—say, April 5, 1972—he can find the headline facts: “68 degrees, cloudy as God sees fit for it to be. Suni is four! Morning paper didn’t come. Walked to Tesco,” etc. I sometimes daydream that there are poetic gems to be discovered—he is after all, the father of my magical wife—but if any exist, they are obscured deep within his impenetrable formality.

When I went to London fifteen years ago to move my in-laws to America, one of the many things I needed to do was sell his car. It was an eighties Volkswagen Golf, maintained so meticulously that it was in showroom condition. When a nice young man came to look at it, I testified to the unusual care by showing him another set of diaries my father-in-law kept concerning the car. Every time he drove anywhere, he entered the mileage, the distance traveled, and other interesting facts, like “Mirrors needed adjusting.” The man was so taken by this practice that he initially conditioned the sale on keeping the diaries. I was happy to provide them with the car, but my father-in-law, surprising me, insisted that that was not possible. The diaries were his personal property. I thought they had no meaning separate from the car, but he differed. The man bought the car anyway but emailed me a month later to see if there had been a change of heart about the diaries. It felt wrong to me to not give them; their dry technical nature seemed more like the car’s history than my father-in-law’s. But he had not budged.

I don’t think this young man wanted them for their historical record. No mechanic would ever need to reference the entries. He saw something else in them: the fleeting reflection of a man’s careful life.

I have not heard him read any recent journal entries but I’m quite certain they mostly concern apples, chocolate and trash pickup. These three things have what seems a religious significance to him. Today he confided to me that there were a few items of trash still in the bin after garbage pickup this morning. He removed the trash and put it in the neighbor’s bin. He asked me after a little laugh, “Do you think God will forgive me?”

People say old age is a return to childhood, and obviously in many ways this is true for him, but children are little narcissists and virtually nothing of my father-in-law’s ego remains. His life is a small sweet circle. He is like a little Dalai Lama or hyperlocal Johnny Appleseed. Is he a bit demented? Yes, of course, but in the most lovely of ways. He is a beacon for all those who have dementia in their future.

My father-in-law used to be the storyteller in the family, or so I’ve been told, but his memories have similarly pared down. He seems to have three, but one of them predominates. It is about a little girl who asked him to marry her when he was six. It fills him with as much happiness as it probably did that day eighty-seven years ago. The story never particularly pleases my mother-in-law.

Behind any demented man one will often find a hardworking woman. Unlike my mother-in-law, I don’t have to do too much for him: mainly I need to eat apples and chocolate, and even that I sometimes shirk by secretly composting them. Even though I’ve taken care of him a couple of times when my wife and Mum, as I call my mother-in-law, went to India, I’m sure I really don’t know what it’s like to live with him. He’s on his best behavior with me. In India they have a saying about the son-in-law being God. It’s a lovely saying, if you ask me, and with great power comes great responsibility, but also insulation and comfort. I know that with Mum he does not begin every interaction with a laugh, that’s for sure. She has a different set of challenges. And when I’m up late, because she’s a night owl, she sometimes sits down with me at 2:00 a.m. and it all comes pouring out, stories and tears. I suspect she’s a night owl because she finds great relief in the hours when he’s asleep. He’s asleep like clockwork at 10:30. At 10:30, my mother-in-law is free of his constant needs, but also free to be haunted by her own set of demons.

If I happen to be in the kitchen in the Ammamma hours, as my youngest son refers to them—the hours after midnight; Ammamma being the Telugu word for grandma—she will sit down and begin to unfold. There is no other time in the day that she will actually sit at our table. All day long she putters around the house, ceaselessly, sweeping and doing mysterious little chores. One of these chores is emptying the rubbish bins throughout the house. For a slow-moving old lady, she does this mysteriously often and fast. Numerous guests have marveled over how it was that something they put in a bathroom bin vanished just a short time later. They are amazed to hear it was the grandmother in the basement. It occurs to me only now that my in-laws share an obsession with trash.

But any night I happen to be up late, I’ll catch her in my kitchen and an old-world grief will pour forth. I’ve heard it many times, but it always transfixes me for a bit. I’ll pull a chair out from the kitchen table for her as she waxes and, unlike any other time of day, she’ll take the seat graciously. It’s not my father-in-law that haunts her at these times. It is always memories from back in India, before electricity was brought in, when the milkman came with his cow and milked it right into her jug. She begins with stories of injustice and unfairness to her, the youngest daughter-in-law in the extended family. She weeps as she recites. She unravels a litany of memories, being cruelly teased and unloved, not by parents but by siblings and most viciously by sisters-in-law. Her story is Beauty and Beast, though she won’t tell me she was a beauty, and she won’t call anyone a beast. She recites it without pride, but I know she is beautiful and thin and hard working, caring diligently for her mother and father, or, depending on where in the timeline we are, her uncle and father-in-law. By a strange Indian twist, her uncle is her father-in-law. Her sisters-in-law are fat and lazy and take particular delight in her torture. Her story always begins in her uncle’s house when she is newly married around 1952 and unable to get pregnant.

Eventually, if I sit long enough, the stories wend their way past the petty hurts and settle into something more painful for her—painful because it’s solid, beautiful and lost. She returns a little further back in time to the events that have fueled so much of her ninety-one years. She’s in Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh, in the 1940s. Her father, who is to die too young, is an accomplished lawyer who hosts the elite of India in her house. She wants for nothing, though even then, I suspect her wants are so minimal: sweet peda, a laddoo, perhaps a lipstick that her friends wouldn’t dare ask their parents for, affection. When she wanted something she would ask her father and he would say, “Take five rupees from my coat.” She would take ten. Later in the day, while massaging his feet as she did almost every day, she’d confess: “Nana, I took ten rupees”. She says one could not lie to such a man. And he would smile. She rejoices in the dignity of the house. She is now fully with her Nana, a man who was constitutionally unable to get angry.

But in 1949 her father dies. She says he decides to die. His wife, her mother, has passed recently from illness. Her parents were several days apart in age and he says to her, “We came into the world together and now we should pass together,” and so he does. She believes he willed his own death, leaving her to the mercies of the extended family of which he was the paterfamilias. She is only sad, not bitter.

There is no need to tell more of her stories here; let me just say they are refined, petrified grief. They fall out almost the same way each night and cast the same shadows. Her grief has become as routinized as her rubbish pickup. I could trace them out on the kitchen walls like the late-night shadows that fall in that room only in the Ammamma hours. But this grief is a place she seeks out, not something ever elicited. She is her own grief counselor and I am her witness.

At ninety-one, she now mourns the passing of almost everyone she has ever known. Tears stream down her face from the long list of those gone, even the sisters-in-law that tortured her. I think she wonders why she cannot, like her father, will herself to die. Lord knows she tells us all many times a week that she wants that, that she is simply waiting.

After an hour I’ll have had my fill. There is no consoling her, she is impenetrable. She is alone, delivering a monologue—but she’ll smile at me as I stand up, because I was there to listen. When I get up to leave, she will empty and clean the bins in the kitchen, leaving them in their place to be filled again tomorrow. I think she knows she is loved, but I’m not sure. She doesn’t make clear that she accepts it. We cannot love her the way she seems to need.

In a few hours my father-in-law will come upstairs and my wife or one of my sons will say, “Yes please,” and the shuffle of giving will continue. He has become the person that he is by the grace of his wife, my mother in-law, who makes sure his every need is met. Because his needs are met, he can now meet what he thinks are the needs of other people.

For years I’ve implored my father-in-law to let Mum sleep in in the morning. Though a teetotaler herself, she was almost certainly on a bender the night before. He seems to mostly grant this these days, though when he can’t find the bread or anything at all, he’ll wake her up anyway. “Yem-andi,” I hear him imploring her as she lies asleep. “Hey dear!” I hear this word intoned throughout the day. “Yem-andi,” “Yem-andi.” When she wakes she will find the bread for him where it always is, and begin her chores again. But what she is really doing is biding the time until 10:30, when she can take flight into her sad twilight and see her Nana again, to visit that saddest place. The least I can do for her is to listen again when she takes the seat I offer. I should be there more evenings, to learn to say to her, “Yes please,” in the way we say “Yes” to the spring and “Yes” to the winter or “Yes” to the apples. My father-in-law comes each day with one word, so easy to assent to. My mother-in-law comes each night with ten thousand that no one in my house has learned to bear. My in-laws are the seasons of my house, the slowing jet stream that gently pushes us forward to our own inevitability. The sun rises with my father-in-law and it sets with my mum and the whole house rests on top of a basement where my two little in-laws have come to see it all off with us.