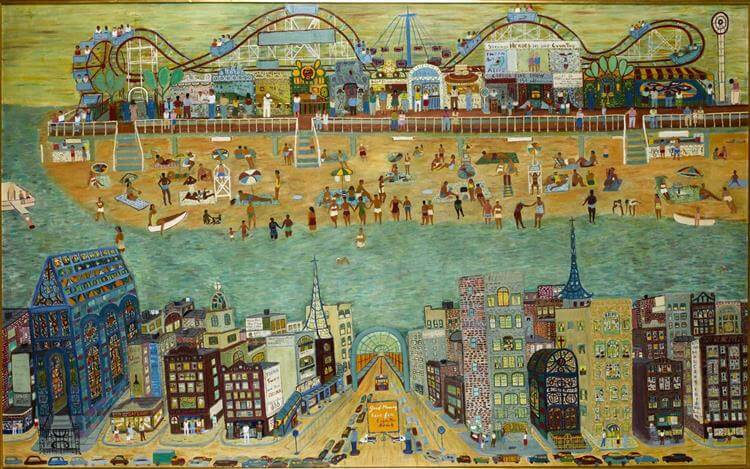

I was on my way to Coney Island. I wanted to see the freaks. Coney Island is famous for them. I wanted to find out if the freaks were still there, or if they had all died. Also, I wanted to ride on the rides, which might kill you, and may have killed the freaks. I had just returned to New York City after a long time away.

I had spent the winter nursing the dream of a city I thought I remembered: New York, a bohemian paradise, and an unhinged jungle of art and magic. New York was famous for its freaks, with stories of freaks who had built kingdoms of freaks, their mouths stuffed with oranges and other people’s teeth and their blood running with street drugs and raw eccentricity and art and music. Does the kingdom still exist? Or had it been bulldozed years ago by rent increases? I didn’t know and I was scared. Scared and alone. If I was turning over rocks and finding answers I didn’t like, I would have to turn around and leave. I wouldn’t be able to face it. If I lifted a rock, expecting to find a freak, and I came face-to-face with a normal person, then I would be truly scared.

I had trouble figuring out where to live. Housing was so expensive that I couldn’t afford to rent an apartment. Apartments required pay stubs, proof of an income I didn’t have. I was just an unemployed, unpublished writer—and I wasn’t writing. So I found a temporary squat at my father’s house. My father was gone, and I was taking care of his bird. It was a mourning dove named Zoi—the Greek word for life—that he kept in a cage. It was never allowed to leave, and spent its days alone, repeating a mournful song as it stared out the bars, shitting in its food supply. There had been another bird in the cage years earlier, but Zoe had murdered it, bludgeoned it to death with his beak. Now Zoi was alone. Except for me - I was there. I had told my father that it was inhumane to keep a bird in a cage and never let it fly. I had told him it might be happier dead. I tried to persuade him to set it free, or at least kill it, but he wouldn’t listen.

My money was almost gone, and so I called up my editor. He offered me seventy-five dollars to write an article. This was exactly what I needed—I knew I had to start immediately. My editor told me to write something on Coney Island and I agreed.

I have a lot of nostalgia for the past. Not only my past, but society’s past as I imagine it.

Once, in middle school, I asked my history teacher if he ever wished he was alive in the 1960s. “No,” he said, “There were people getting lynched in the ‘60s.” These days, I feel as if all of my precious experiences are slipping out of a hole in my brain, like indifferent eels. My memories are raw steaks sitting alone in tall grasses of noise. Noise of memories I can’t remember, unheard thoughts of other people, and car traffic. My memories are like homemade chess pieces, whittled down from the tree of experience. When I try to cook them, because I think they are steaks, they become tough.

My friend Carl, a photographer, came down to Coney Island with me and took some photos while I interviewed people on the boardwalk. “I’m in pain,” he told me, “My hands have been cramping up, and I’m in excruciating pain.” He didn’t know what was causing the pain, but he began eating weed gummies to cope, and the weed gummies were causing him anxiety. “I’m high all the time,” he told me. “And I bought one bag of gummies that turned out to be rancid, and they fucked up my stomach and gave me the shits. But I couldn’t stop eating them, because then the pain would come back.”

“This is the wrong camera,” he said, “I should’ve brought a different camera. This is a studio camera. It’s not right for this project.” Carl had stopped doing photo-shoot work because of the pain.

The Park was closed. The rides weren’t on, because it was a weekday and too early in the summer. The sun was bright, and we could hear the cries of a man yelling “One dollar water” over and over. A ragged figure covered in sand lay in the middle of the beach groaning, surrounded by seagulls that were pecking at a box of decimated chicken that rested on his outstretched hand. Down towards the water, a metal palm tree slouched stiffly in the breeze. We smoked a joint.

As we were smoking, two French teenagers approached us, and asked if they could buy some of our weed. They told us about their experience of New York.

“We were in Brooklyn, and we saw a lot of… different people. And we think it’s, erm, a little bit ghetto… In France, when people are in the street, it’s a little bit scary. Do you know where we can go and not see these people?”

“Homeless people?” I asked.

“Yes,” the boy said, “In France, homeless people are scary because… they like to scare you. They shout at you in public.”

We wandered down the boardwalk without the French kids and stumbled upon a group of vagabonds. They had hopped a boxcar up from Mississippi, and they were excited to show us an array of treasures they had found along the way. One man, who called himself Bill the Rubber Tramp, showed me a large metal chain he kept on his belt, with a mailbox key that opened any mailbox in the country. He had found it while sleeping in a post office. When I asked where they were headed, the guy told me that one of their friends' parents had died, and they were on their way to West Virginia to buy property with the insurance settlement. He said he was going to set up a still, brew his own liquor and grow his own tobacco, and “grow some fucking carrots or something.”

Because the park was closed, there were no tourists or kids around, and no one was playing the games. Still, people had come to Coney Island looking for something. A man with a floppy hat fishing for flounder told us that catching one keeper for the season would be lucky. Commercial fishing had emptied the area. “Twenty years ago,” he said, “you could get a bucket full in a few hours.” Now, there was nothing.

As I walked past a temporary tattoo stand, a man in full military uniform with a camouflage cowboy hat popped out from behind an animatronic clown. He ran one of the game booths, and was eager to talk about the history of Coney Island. He told me that Harpo Marx had held auditions for the Marx brothers in Coney Island. He told me that the parachute jump was used for military training, and he told me about the yellow submarine on 23rd street. The submarine was built to search for gold at the shipwreck of the Andrea Doria, but it was too heavy to be lifted by the crane that was supposed to drop it in the water. They removed key elements of the submarine so it could be lifted by the crane, but forgot to re-attach them before the submarine was lowered into the water, and it capsized. Now it sits immobile in a park.

He said that everyone in Coney Island was talking about the casino. New York was looking for a place to put a casino. Coney Island was one of the contenders. The game operators were worried that the casino would displace less popular games, like the stupid basketball toss. One thing was for sure: if they built a casino, Coney Island would change. I left Coney Island that day but I knew I would come back. I had to—my editor was breathing down my neck for the essay and I needed the seventy-five dollars.

Without a job or any obligations, I began visiting open mic nights in the city. The kind of people who wait for hours in a tiny bar to play for four minutes to a group of strangers are often eccentric, and most of them are entirely unconcerned with the world around them. Maybe I could catch some in a net and present them to my editor, who I knew was foaming at the mouth for some delicious freaks.

I visited an open mic at the Music Inn, a music venue and instrument store in Greenwich village that had been around since the 1960s. It was a tiny, messy space with a cramped ground floor and a basement, and it was so jammed with lutes that you could barely pivot without destroying the whole shop. All the regulars, especially the old men, hung out in chairs outside, drinking tall-boys from the bodega next door, and leering at the college girls who frequented the place in droves. This place where Bob Dylan had once been a regular was still hanging on. It was a true vestige of New York’s artistic past. The energy was awful.

After many nights of watching strangers perform, I began to feel inspired myself, and so I began to perform onstage with a piece of fruit. I put a Mango on a stool in the center of the stage with a microphone aimed at it. I explained to everyone that I believed the Mango could be a great singer but that mangos are often shy. Together we encouraged the Mango to sing, shouting affirmations at it, and telling it that it had a beautiful voice. Then we waited, but the Mango did not sing. Next time I performed with an Onion, and I gave it more time to sing, waiting for several minutes while I sat in the audience and ate snacks. Still, the fruit did not sing. Finally I tried to persuade an Orange to dance. I knew it would be great if it could just muster up the courage. I put on a song for it and ate snacks for ten minutes, waiting patiently with the audience. The Orange did not dance but I thought maybe it had come close.

After my last performance a very tall man with a bald spot and an Irish accent walked up to me. He shook my hand and invited me to attend his class for clowns. When I showed up to the class, which was on the fifth floor of an unmarked building in Chinatown, the room was very hot and smelled like body odor. One by one, the students would perform, entering from behind a curtain, and the tall man would criticize and mock them. The class was three hours long, but when I left I felt good.

The next time I went to the clown class the teacher was especially irritable. At a certain point he turned around and addressed the class. “I’m sorry if I seem angry today—last week my wife of twenty years left me. I didn’t see it coming at all. She told me she is not in love with me anymore and in fact has been seeing someone else for a long time. Now I have nowhere to go and I’ve been sleeping on a friend’s couch in Queens” At the very end of the class, he instructed a performer to imitate him, after finding out his wife of twenty years was leaving him. The performer threatened his imaginary wife with an imaginary gun. Afterwards, everyone clapped, and again I left the class feeling good.

I began attending clown shows. One of these shows was a monthly showcase called “The Dime Show,” where tickets only cost a dime. In the show was a jovial clown in a patchwork dress who had just arrived from Switzerland, and a person in a gimp suit and leather stilettos who tore through the back of a picture frame and knitted a hat for their grandmother. There were many other performers, and upstairs, in the bar, a woman wheeled around a cart of heart-shaped jewelry and heart-shaped sunglasses that turned every light into a rainbow heart. Later I saw this same woman in Coney Island, at the annual Mermaid Parade.

Because I was writing a piece on Coney Island, I knew I could not miss the parade. I again invited my friend Carl, the photographer, along with my new friends Sander and Amala. On the subway ride out, I listened to the Lou Reed album Coney Island Baby. I couldn’t understand most of what he was saying. In one song he talked about getting turned on by a woman slitting some guy's throat in a bar. On another, he sang several times that he was “a gift to the women of the world.” At the end, he said he was a “Coney Island Baby.”

The parade moved too slow, and I got bored. The most interesting part was when I rounded a corner to get a candy apple and saw a man fighting the police. There was blood running from his mouth, and it looked as if he had bitten off his own tongue.

Maybe I was bored by the parade because I don’t like parades. When my new friends Sander and Amala showed up, I was happy to see them. I had met them at an open mic in Queens, and they were both unemployed.

They lived in a small apartment that was filled with old knick-knacks that Sander had picked up off street corners.They had both come to New York from much sunnier places. Amala was from Australia, and Sander was from California. When Sander was a child, his parents would find him on the roof writing poetry and gazing at the stars. They saw this as evidence of his insanity, and had him committed to a psychiatric hospital where his dad told the doctors that he had been huffing lemon Pledge cleaning solution. One day he came home to find his house boarded up. His parents had split up and left town. So Sander moved into his car. As a teenager, Sander had written songs for a famous musician who later stole all his material.

I met lots of musicians—unable to live off their meager earnings, they all survived in different ways. Isaac sang in churches. He was an opera singer and a pianist, and would often launch into unprompted melodies, make strange sounds with his mouth, or say things like “This falafel tastes like an E flat!” My friend Torture had just moved back to the country form liverpool and worked three jobs that barely covered her expenses.She seemed to know everyone, and would stay out late, drinking heavily, and chatting manically. I wondered if at her age I had possessed a similar energy. Now I was tired, my body ached, I had a persistent skin rash, and I pined for the artistic worlds that were long gone before I was born.

I got a job washing empty glasses in a cocktail bar. They made their money hosting DJ parties. NYU students would twerk on the booths, knocking over glasses, and when the glasses shattered and covered the floor in broken glass, they would dance on the broken glass. I would have to get on my knees and pick the glass up with my fingers, while I thanked them. During the days, I wandered around with Sander and Amala, watching Sander comb the street-corners for trash, and listening to Amala tell stories of the rare and fearsome creatures of her home back in Australia.

I began to feel lost. Every day was a carousel of urban amusements turning endlessly. Yet I found so little that amused me. It was like a million delightful bells were chiming intermittently — and you wondered what they meant, until you realized that they were being rung by an anthropomorphic strawberry, with dementia, who lived on a mountain of gold, and had forgotten what was happening. My time was skewed by an economy of fabricated revelry, and my mind was skewered by an economy of freaks- a meaningless economy of freaks, a stock market of fake and real ones that dithered on the precipice of a crash.

The market was close to a realization that its whole construction was worthless. What need is there for the soul of a freak when we can be entertained simply by an animated dog with no legs? The soul of a freak is delicate, fragile; it needs constant reassurances and special snacks; it needs purpose beyond the empty commerce of a vegetable market that only sells pictures of vegetables. Somewhere along the way, the world had agreed that the soul of a freak was too costly. Far more efficient, they had decided to affix the trappings of the freak to common schoolyard geese and make them run with electric charge under the ground. Now, the freaks were everywhere, like discarded furniture, like popcorn on the floor. They were ubiquitous, but unwanted, untended, and worthless.

I saw torn and ragged freaks, their eyes flashing with desperation, jousting with enormous carrots in the bowels of a neon playground for the aristocracy. I saw a giant piece of cinnamon bread descend down on one of them and swallow him up in one gulp. I saw an evil watering can rain empty ideas on the freaks as they slept. I saw into their dreams, wherein a flip-book of dead freaks was sold to a child by a robot-dog with the face of a smiling doctor.

“NO!” I shouted, alarmed at these visions. I tried to snap myself out of my stupid nightmare. I needed to finish my article, so I called up Dick Zigun, the founder of the Coney Island Freak Show.

When I arrived at the Coney Island brewery to meet Dick, he was sitting with some friends, drinking stout out of a plastic cup at two pm. After my horrible nightmare, I was looking for emotional salve from some kind of artistic authority, some freak-king, who could pat me on the back and tell me that, in fact, the kingdom of the freaks was alive and well. Instead, Dick told me that Coney Island was a series of real estate scams. Coney Island as an amusement park was started by someone who saw the world’s largest ferris wheel at the world’s fair, built their own smaller Ferris wheel by the beach in Coney Island, and then told people it was the world’s largest Ferris wheel.

Dick told me he supported the proposed casino in the area, the only business he said was “guaranteed to succeed year-round”.

Dick had arrived in the late ‘70s, looking for cheap spaces to host art events. He was the one who started the annual Mermaid Parade. “For a decade and half the media every summer said ‘Murder Gangs Arson, Murder Gangs Arson, Murder Gangs Arson,’ and then suddenly—’Mermaid Parade.’”

Dick had also started the Coney Island Freak show and credited himself with creating the neo-burlesque movement in the United States. He had recently left the organization he founded, Coney Island USA, due to a disagreement about his pension. After all this, I asked Dick what his next move would be. He told me his priority was putting on an all-blue fireworks show, because blue is the most difficult, rarest, and most expensive color of fireworks.