I. Joe the Newsman and Bobby the Detective

“Good evening. After years of thinking that everyone was the same, scientists have discovered that people are different. Our experiences make us different and our jobs make our experiences. Charlie Chaplin made this discovery in his movie Modern Times. The main character is a bolt-screwer, who, as a consequence of screwing bolts, sees the world as bolts to be screwed. He confuses the breast-pocket buttons of a lady for two bolts. His workplace made him into a worker on the world. He had one perspective as a result of doing one thing all day and went to jail as a consequence. To avoid this problem, we will have twenty professions. Scientists urge the public to adopt this position but the public won’t listen—it demands affirmation, like a child!

There is only one ray of light—the new show called Undercover Boss. In it, CEOs work in disguise alongside their laborers and get to have two viewpoints instead of one. The rest of us walk in circles, as do addled horses. We race the same track always in the same direction. Tonight: Who built the tracks on which our lives run? Now, to our sponsors, ‘US Track Builders.’

Folks, I’m just horsing around.

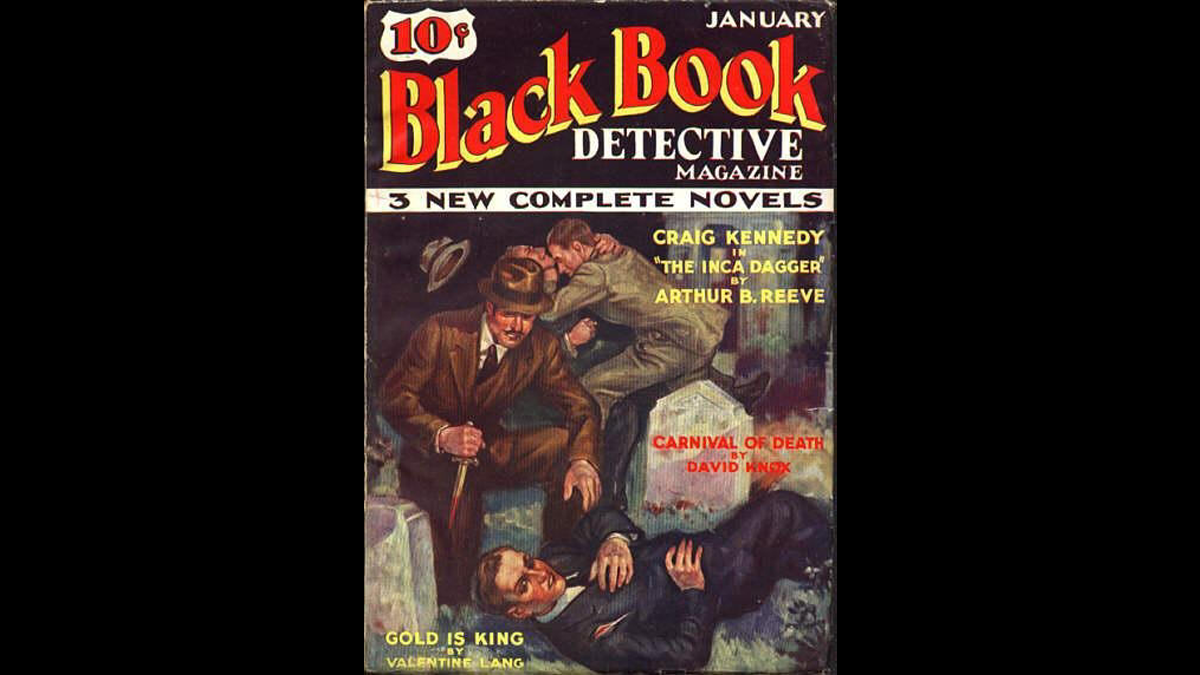

Our next guest is the retired detective. He never clocked off, thought a newspaper could be ‘solved’, called the president a ‘mob boss’, and ‘anyone and everyone’ stands accused in his first trial of the world.

Tonight: Should we all be the world’s detective? Tonight: Are illness and genius the same?”

While waiting for the show to begin, Joe the Detective sits in the make-up room waiting to speak at the podium. In his countenance are rain-filled years. Rough time also gathers in the form of ripples around his eyes. His forehead shows the storm of eras. He solves a crime at the very last moment.

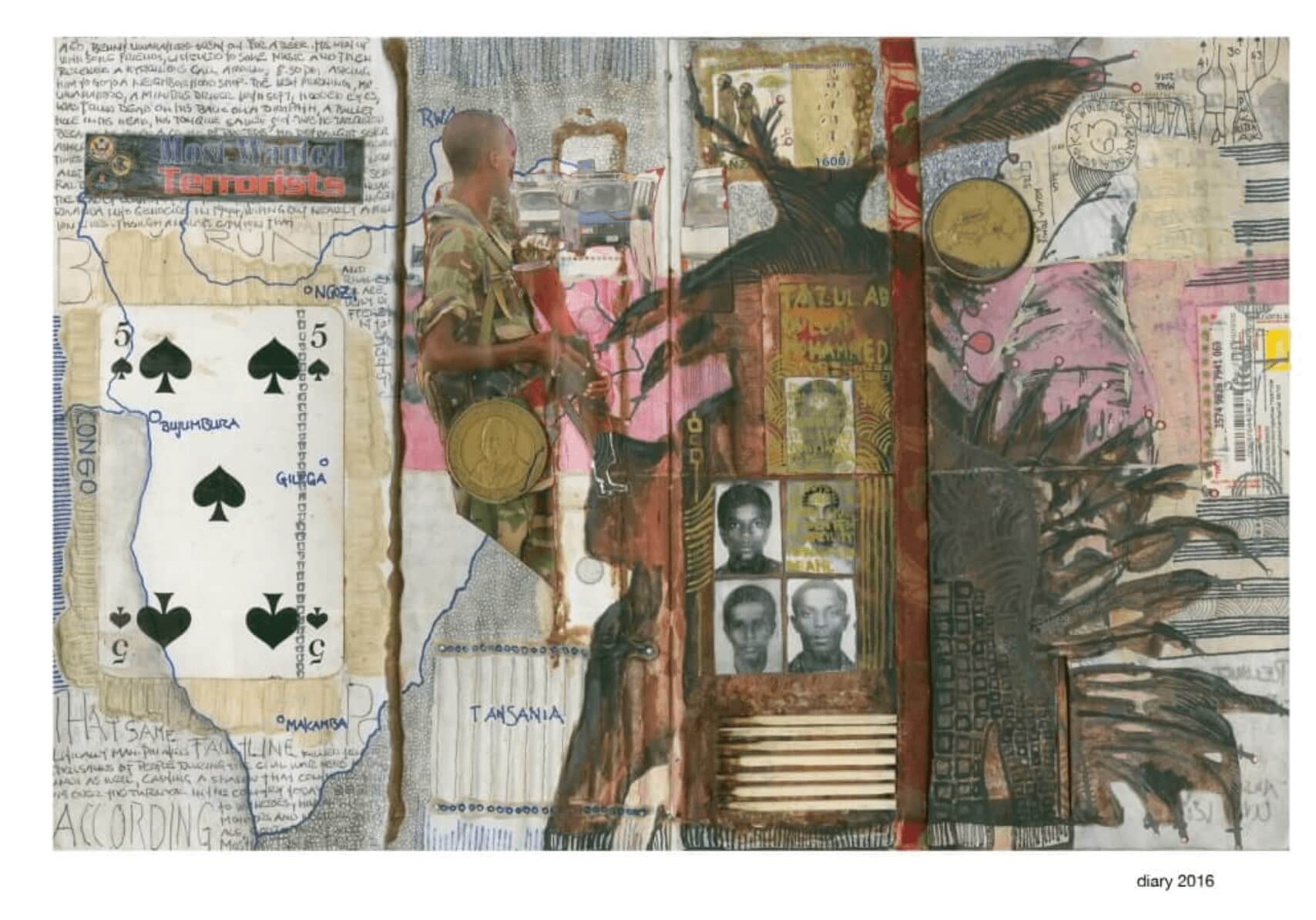

Using a red thread crime board, he identifies connections denied by the main-street rabble. “Hurricane Strikes the Coast.” He places this in the circle marked “Disaster.” “Big Oil makes a Big Fortune.” He places this in the circle marked “Profits.” “Zuckerberg Unrolls New Games.” He places this in the circle marked “Prophets.” The great and wary detective connects his three piles with a single thread. At this point, the world seems to say, as if distracted from its business: “Am I my brother’s keeper?” Then the blue pressroom cadre murmurs. Joe the Detective arrives on screen and disturbs their thoughtless hum.

At the podium, he says: “Ladies and gentleman police, honorable mayors, the clues were right under our noses.” Then the crowd goes wild.

“Exhibit A: Disasters. B: Profits. C: Prophets.”

He says “We got it all wrong.” The crowd goes wild.

He continues. “Greed causes hurricanes to occur. Meanwhile moonshine turns us from ourselves and our abandon. There is crime everywhere, though few care to watch. Time to watch. Time to round ‘em up. We need a police car as wide as the continent. Everyone is indicted, and let me call the damn president…” The crowd changes its mood in response to his challenges. They throw rotten tomatoes at the correct detective. They love the damn president. Widespread ignorance impedes him—so he has to scrub tomatoes from his coat.

Once imprisoned, he begins to rattle out the melody for a new song, using the spoon and grating. The title is: “Song of a Just Prisoner.”

Then the show is over. Bobby the Newsman concludes: “And so we see – detectives of life go to prison. In my opinion, illness and genius are the same. Good luck everyone. Kiss your wives and children.”

Bobby the Newsman drives his car home. At every stoplight, fans smooch his car window. He hands out smooched papers through a mail-slot, then sits in his living room, surrounded by smooched papers. While reflecting on the character of his work, he says, “If you don’t watch, I don’t eat.” He says this to himself today, while eating a round steak, then to his viewers tomorrow, in the throne of the host. Then the president arrives on television.

Bobby greets the standing President. “Mr. President….” he begins. “Mr. President…” The president watches his smiling face in a thousand smiling eyes.

In prison, the tomato covered detective pawns his prized bowler for a metal spoon.

“Mr. President…”

“Yes, my dear?” says the president, with a wink. The crowd beats its breast, then buries the president in thrown roses. Newsroom staffers sweep him out after he extends, from the midst of “Rose Mountain,” the white flag of mercy.

“Mr. President, did you implant—?”

“Outrageous!”

“the destructive, monstrous—”

“Scandal!”

“dictator?”

“Soulless accusation!”

Sweat forms on the president’s brow, which he dabs with a tie made from soiled flags.

“So what if I did…”

The audience gasps in a famous harmony called, “The Song of Ideas Dawning.” The president scans left and right as would a criminal hounded by car-lights. Two trucks of rotten tomatoes arrive. The rose grower’s association disbands. Investors take note of the ailing rose business.

The president says, “And I would have gotten away with it too, if it weren’t for—” at the moment when the detective arrives, carrying a sharpened spoon. To restore his dignity, he wears a tin-foil bowler. A small number of roses gather in honor around him. One loyalist throws a cherry tomato. The rose company is back in business. The rotten tomato company has never worried about business!

The newsman turns the case over. The audience becomes the grand jury then waits to see if men are good. In the leader’s rusty smile is a guilt in bloom—his self-condemnation is like a budding flower. Roses gather by the hundred around the detective while tomatoes gather on the president. These days justice takes the form of thrown roses. Rotten tomatoes dole out criticism to those deserving. The newsman is almost like God in the way that he’s in the background just seeming… I dunno…to make it go alright…

The detective returns to his office to smoke a cigar. His newspapers stand all together in a row to sing condemnations. Then it’s time to stop seeing so many pictures of blood and men dying over a spoonful. “Detective, what are you doing?” cries Bobby the Newsman. “I solved the cases, so I don’t need the papers anymore, I can use them to light my cigar, like this,” says the detective. Using the shroud of history, he lights another Cuban. “Everything goes up in smoke!” reads the evaporating headline.

Joe the Detective goes to the riverbank to contemplate the contours of tragedy. He blows cigar smoke in the direction of a heron’s nest, then watches the bird recoil from the smell of tobacco. He continues to smoke. Soon the bird longs for more—that’s how it is, isn’t it? He extends his box of Havanas to the gracious creature. Bobby the Newsman records this encounter from his television van. He records the co-existence of green factory waste and violent turtles. “Whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” say both men, with regard to related phenomena. The heron begins to make its own cigars, the turtles begin to fight for pay.

II. Bobby the Newsman at Home

In the previous episode: Bobby the Newsman ensnares the President on late night television. Joe the Detective provides concrete evidence against the world in general and the president in particular. He is defamed and imprisoned for this act. Later vindicated by the president’s own admissions, Joe goes contentedly home, lighting his cigar with burning headlines. Narrator describes newspaper as “The Shroud of History” and gives other interesting descriptions, often of one thing in terms of another. Protagonists marvel at nature’s ability to change.

Bobby the Newsman sits by the red fire in his glass home. Onlookers gather outside to see him model a pipe-smoking habit. Foreign as another country are their fellow feelings—these fly up rarely then fall like downed birds. Men stepping on one another’s toes are reprimanded and cast to the fire. With his feet laid up, Bobby the Newsman stares before him and lights his cherry pipe for the screen. Warm as a rich red fire is the gleam of his transparent life. He calls the flames of America’s soul (his fire is the nation’s soul) by name: “Friends, countrymen… dames, girlies…. Madame Secretary! The man in the moonnnn,” he sings, “the Energizer bunny, the Coca Cola bears…” and the list goes on. In response to the global act of recognition, the fire purrs… warmly.

Onlookers outside model their own pipe-smoking habits. They take out their pipes at 8 Eastern, 7 Central, 6 Pacific Standard Time. Later Bobby the Newsman dines. The food repository provides him with inspiration for the nightly meal. A steel bureau containing folders of meals is labelled for each day of the week with proper portions of meat and vegetables—“just like the doctor ordered” is the note on every folder.

Joe the Detective, the dogged world conscience, meanwhile runs his last-place lap in the race for more time. His old prison writings circulate in sewer towns that waft up criticism in the form of a foul stench—crowds outside of Bobby’s windows place fans before the grates to blow sad words into poorer areas. “The reason why people knock on their TV screens is because they think it will bring the good world into their own,” is Joe’s latest. “The reason why people knock on their tv screens is because they like to see me dance,” says Bobby.

Joe replies: “If they stopped knocking, you’d stop dancing.”

“If I stopped dancing, then so would the people.”

At a crossroads again they both blurt: “What’s it to you, anyway?” and Joe stalks away as Bobby stalks back into his home.

Burly wrestlers escort Joe the Detective from the premises: but as he struggles away, he slips letters through their huge arms, and they slide through the doggy slot of the door to the home of all values.

Bobby reads them and weeps, in his one dark corner—but in public he throws Joe’s letter to the fire. The fire in this way is lovingly tended; its name is “America’s Soul.”

In his living room, Bobby makes a show of throwing all Joe’s correspondence to the flame. Its after-dinner belch is called, “American Satisfaction,” or “The sound of a sure-footed soul.” Bobby shows the burned letters to city dwellers, small business owners, and lone wolf types, who enjoy seeing criticism wasted and turned into coal. Joe asks his colleague to disappear from television. Bobby replies wryly that a worse man will replace him. During their rare river sojourns they walk arm in arm.

The fighting turtles grapple for sideways views of the ying and yang of thinking, living people. The mafia network of smoking geese also honk a weary trade. Respect and hatred mix in the men queerly, and they seem to kiss and fight alternately—not literally but in the glances and words they share. “I wish you would change,” say both men, seeing that nothing changes, that even the turtle police force has begun to run private brothels.

Single men, living in shacks to avoid their creditors, crawl out from their private hells, to watch this rare exchange. It lends meaning to their ensuing fight. They join parades of socialites; presidents march with underlings, and the last with the first into taverns, inns, and stadiums, to watch the national show. Bobby talks to them from beside his fire after the river sojourns. Wherever the show plays, you can call it a home. Bobby the Newsman is “the nation’s conscience” but as he says, “It is up still to you to listen.” It listens often enough.

“The problem, the problem,” says Joe the Detective, cursing now, and splashing his boots beneath a lamppost on wheels, itself attached to a raincloud that follows him only, “is when your conscience ain’t any good.” Orange light illuminates his private cone of rain; this forms the atmosphere of Joe’s sentiments. A homeless individual approves of the beliefs suggested by Joe’s hard look and mud-soaked clothing. From the sewer grate where she is confined, her eyes shine like a lantern in the mist of the world.

Joe kisses all the sewer-bound angels. They say to him in chorus: “We shine as lanterns through the mist of the world.”

Nighttimes Bobby cleans his glass home corridor. The wall decorations come from log cabin interiors, trailers, and foreclosed American palaces, and the walls are also adorned with pictures of presidents, breasts, and cars. Christmas Music plays at a roaring volume throughout his home.

Joe stands outside whispering revolutionary poems to disaffected newsboys. Passersby, who either approve or disprove of Joe’s rain-soaked viewpoints, jostle him or kiss him accordingly. Some draw the sign of the cross on his chest or ask him to stay away from the children. Is it strange that admirers of Bobby could also see wisdom in Joe? Standing as they do for opposite visions of life one would imagine that the kisser of one could not kiss the other.

“You just get tired, don’t you, watching the same old song and dance, called the ‘the waltz of the just and the foolish’?” asks Joe the Detective. “My friend, the line isn’t so clear,” says Bobby the Newsman, “Main Street, Wall Street, boy, girl, black, white, peace, war, the line just isn’t so clear these days.” Bobby looks into the fire, which looks back in anticipation of a wise line. Then he says, “When the just and the foolish face one another in a duel, each sees a fool standing across from him.” The fire burps. Joe replies, “But a judge, who is external and impartial, he would surely know the fool and know the just man.” Bobby laughs, with his head tucked into a red bandana. “There’s no judge in a duel Joe… Just the one who draws quickest!” In a flash Bobby draws a cigarette from his pocket. “Quick-Draw Cigs: The Cigarette of Wisdom” reads the advertisement.

Joe stands outside and watches Bobby’s smoking contentment. He stands apart by virtue of his virtue. The crowd is tired and hungry, every one in their own way. The rich are tired and hungry, but tired of wealth, and hungry for meaning—they link arms with the poor, who are tired of meaning, and hungry for bread. The executive class holds out a silver platter in hopes of a sated conscience. The working class holds out its rough and dirty hand for a piece of the pie. Desperation in both pairs of eyes, despair, trouble and sickness in both kinds of eyes regardless, regardless.

“Why do you come here on Friday nights?” asks Joe to a random passerby. “Why hold up a caricature for a standard? Why believe in dreams? Why march here, when the revolution will not be televised? Why take opiates? Starve the spirit for a ticket to ride?”

An anonymous passerby presents, in response, a volume of family pictures. Behind school-portraits of her children, pictures of her dogs, and pictures of her wedding, are distant photographs of Bobby in his glass home, tending to the roaring fire or frying eggs. She also owns a signed photograph of the fire named “America’s Soul.” In some pictures you can see in the fire a proud lion’s form, and others a weary, old jungle cat, and in the newest a mute ape who can’t think about the future or the past, but beats his broad chest in the present forever. “These moments”, she seems to say, “are as much a part of me as my own dogs and family.”

This makes Joe recall the man he’s known, but dimly, from his earliest childhood. “Bobby may not have a soul” is his private thought.

But it is not really a private thought—nothing is; every thought will emerge in daytime. Today we have turned this insight to our advantage.

The moment a villain smiles over imagined crimes, an alarm rings in every precinct. This is called the “criminal smile.” It leads us to conclude the following: no divide exists between the inner and outer realms—or—we all live in glass houses. Rain patters on Bobby the Newsman’s glass home, but his feet are laid up by the fire.

Rain begins to fall again on Joe the Detective, soaking his cardboard bowler. This shows the truth of God’s reminder to Job—to bring an umbrella, no matter who you are.

II.V Joe the Detective and Bobby the Newsman Offer:

“A Cosmic Apology”

Dear Crowd,

The extraordinary ambiguity suggested by our lives has led more than one reader to level at us the ambiguous charge of “nihilism.” It also seems that, in our writing, we have addressed a worldwide antagonist. Its hostility to the masses and the just is very present. True believers of every kind (believers in God, Marx, and Democracy) seem to stand on a level with the lowest television personalities—neither good nor evil seems to win, and neither is worth admiring. The good man never gets his due and his cloudy outlook paints good ideas in unbearable colors. The ambiguity of Bobby’s morals suggests that our leaders hide something. Grayness and rain seem to color our outlook. We insist with black-and-white certainty on the truth of grayness and rain.

We regret our actions and views. By way of apology, we offer up the following alternate ending to the previous episode. In this one, order prevails on earth as in heaven:

“Bobby the Newsman and Joe the Detective, occupying different positions of power, and having opposite perspectives, decide after lives of outraged disagreements, to sit down for tea. Joe offers Bobby numerous wise critiques, which Bobby agrees to incorporate into his show; Bobby checks Joe’s simple millenarianism, his Bolshevism, and his unfortunate habit of seeing things as black, white, and covered in rain. Joe learns how to live a little and his private raincloud dissipates. Bobby and Joe lead Americans to conditions of love, which are also the conditions of freedom. The world takes a new turn, and in a moment that assimilates mind and body, domestic and international, religious and scientific affairs, the entire United States population begins to dance…thoughtfully. Throughout the dance they reckon with their role in history and what must be done going forward. The model and oppressor of the entire world becomes its source of liberation. In time the whole world dances to that good ol’ Rock n’ Roll……………”

Ah God! And Uncle Sam! A second apology: we presented the alternate ending in such a way as to get the reader to reject their own rosy views by drowning them in rosiness. Our supposedly sincere letter was produced in the same hostile spirit, sad to say it, as the entire tale that it follows.

We should admit this now: the creator of our show—and this should explain all—is a young, contemplative man, with little to no “real-world experience,” with a great love for self-laceration, who disdains earnestness and success, who references his own unread works critically, who wants praise for this humility, and who (as if this were not enough) thinks that “being understood” is the defining characteristic of animals! No wonder this should all turn out as it does! We cannot imagine how taxing it must be to tune in season after season. It’s all cleverness, and no love.

What could work, as a second apology for a first apology that was less than sincere? How to go on but to go on, the same as before, with broken feet and legs, and a broken yell—always the same pissing against the wind: “I’ll take all of ya, all of ya!”, fists bared, like a red-faced drunk!

And this drunk’s yell, is it supposed to stand in for love? Is this your gift to creation?

Yes it is. This dumb antagonism is, in its own way, done from care—for history to have been better to the drunk, and in an inadvertent way, for it to have been better to everyone else who brought him into being, better to his father, his boss, his brothers and friends who pushed him into the rain. Better to everyone. Here selfishness and selflessness coincide. Hear in the drunk’s red-faced yell his love for the world.

Anyway, that’s our excuse.

Yours,

Bobby and Joe

III. The Jailed President

In the previous episode: Joe the Detective watched Bobby the Newsman in his glass home. Dispositions of both alluded to by the narrator, and connected with elements in their surroundings. Joe lives in a private cone of rain, Bobby a glass home. Bobby was going to prepare the nightly meal when Joe’s stern eyes condemned him. Bobby and Joe later wrote to apologize for the episode, because there was no room for the viewer to breathe and its effect was to make us despise both action and faith. The sincerity of their apology bears consideration. Tonight we visit our old friend, the jailed president, in a favorite setting of the narrator’s: jail.

By replacing a pin-striped suit for an orange one-piece, gourmet meals for animal-grade hash, and the company of arms dealers for that of poorer criminals (for men who commit crimes, but who do not, on the whole, lay the foundation of crime) the president in time learned what, in his mind, he should have learned long ago: “Decency, humility, and submission. The benefits of time alone. The goodness of the common man. How to make spoons into knives.”

A repeat offender shows the president how to carve his way out of hell. “Better you than I, better you than I,” says the old jailbird. The president delivers rolls to the man from out of his shirtsleeves. “Leave with me, leave with me!” he cries to his convicted friend. But the hard soul replies: “Jail suits me. For it’s the same as anywhere else.” This remark causes the president to check his rose-gold viewpoint. He looks out from his cell window and sees more jail outside. A tear, well-suited to a television biography, forms on his creaseless nose.

Gone in spirit, the old and over-dignified prince; no time for mass-murder then golf; here a man made regular through hardship, cut from Adam’s own bone, someone you’d like to get a beer with. But this change took some time.

First he was alone and in his dreams was his famous dog, padding through the white house garden eating prize flowers. Standing at dog level, mouth filled with roses, he stared at the groundskeeper with guilt in his heart. Those days he whimpered in dreams and in waking life. He covered his eyes with his hands. His hands were foreign to hard work and his mind was on the outside world, where pundits remarked on his soft hands. What time he had he marked with a stone.

Some thugs smiled and held out their caps. They took pity on his wretched appearance.

Filthy, singing, ragged lads from below the lowest gutter spat on him and made hard requests. “Mr. President,” they said, “We’d like you to order a war on the cafeteria, a war on the warden, and a war on too much time with nothing to do. Can you do that? And can you make sure it’s the lady troops that’s doing the fighting?” The warden kept slipping him little drawings of crosses and quotes concerning the son of man. The little ragged boys sang outside of his solitary cell:

“We suffered under your regime,

Against our filth.

Your great per-dieme

Would make a many lib’ral cry

If only poverty would bring them, passing by.”

Joe the Detective coordinated with a local songster to provide the boys with notation; an unused pipe connecting the sewer and street ran full of their smuggled music. Just as often songs poured out spontaneously in their harangues and jibes. They sang the following songs extemporaneously: “President Nut Head,” “Mister War-Tax,” “Robber in Chief,” and what has since become a worldwide smash: “Bomb-the-Ghetto-Man.” The president was forced to hear them at all hours.

In jail, he listened to the counsel of old men. Their lives had been drawn on their faces, and their worldview came from harm. Listening to them changed him some way. His old thoughts gave way to bleak and truer visions. Life seemed free from its old worries. The pressure of so many investors and eyes upon him abated and left him with only his own eyes. These accosted him like Christian policemen or nuns bearing nightsticks. These were the images that came to him in dreams induced by poisonous moonshine.

Television meanwhile cried out in the night for its old anchor president. The four thousand people standing outside Bobby’s glass home waited for the breath of life to jump in the old host. But without the president, he had lost his inspiration Accustomed to his moods and changes, the strains in his smile felt like lightening strikes upon the antennas of the world spirit. People saw in one another’s eyes shame and love as opposed to reflection of bright blue. They sought to express themselves and had to borrow the language of presidential addresses. Language comes to them in fits and bursts.

It all makes sense now. Of course they wanted a jailed president—who else could understand a locked-up people?

IV. A Message from the Jailed President:

“End of an Era of Sly Winking”

In the previous episode: The president in jail becomes “the Jailed President.” The transformation process entails having a shameful dream. He pads around the White House garden in nocturnal visions, he learns from regular people, he plans his escape.

“Without an animating purpose I have no appetite for fresh steak,” says Bobby sorrily while microwaving some dried out bones. These steaks resemble tires; he says so in explicit terms—consequently the “image value” of steak and tires fall. Two eagles shot by a starving ad-man die in a dovetailed motion. Plummeting stocks and plunging iconic birds presented side by side in an incisive documentary attempt to show the whole moment.

Bobby thinks to himself, and thus to the whole world, “Because my steak and interviewees arouse no pleasure, I smoke no cigar—and because I smoke no cigar, there is no spark for America’s soul.” Once a roaring fire, the soul is now a whimpering flicker, whispering wispily, fizzling on repeat its near-silent request: “Bring the big man back.” Bobby often looks enjoiningly with the fire in the direction of the jail, as if to say the same.

In the absence of the TV address, Joe the Detective notes the rise of congenial rainclouds sweeping over whole sectors—he states, bittersweetly and with strain, the following message, from his own growing wire service: “News itself is on death row.” Bobby the Newsman makes a counter-request on behalf of his constituents: “The news tonight is: I’ve given up steak. The news tonight is: dry bones. Dry bones is also the forecast tomorrow. Criticism and dark reckonings are what we have to look forward to. The weatherman says: get rid of crime, get rid of entertainment. Get rid of entertainment and you get back crime, this time of the highest order—the crime of having no entertainment.”

And at these words the underworld elements finally mobilize—depending on amusement to perpetuate pain they gather teams of drill-men to bore through the soil in search of his cell. They hope one day that he will bless their bloodied hands—but though they strike gold and pay-dirt, their searches turn up no sovereign. Instead, a network of holes populated by its own mobs and kangaroo courts emerges—strife and protests raging for months in the dirt world exhaust the police force of the Burrow Borough, who, mourning the freedom of new beginnings, long for the settled world above.

Poor officer Innocent, at watch in the dangerous district, smells above him a faint and familiar smell, mixing in one whiff the tumid sweetness of candied lies with the reliable air of corruption. Up through damp passages, his nose leads him to the dreams of old and easy wrong; he taps forcefully the dark ceiling of his world. Roots and fossils fall; all the comforts he used to enjoy, cigars and sports broadcasts, tax islands and wiretaps, gather as hidden rubble from the world above. Then the president tumbles out, his body crumpled like a dirty dollar. Tears stream down the officer’s sweet and longing eyes, as if he had just found a dirty dollar.

The president then shakes the man’s hand and, from sheer habit of bribery, gives him a dirty dollar.

The president apologizes just as swiftly, but the gathered officers smile to see the old tradition. They greet it with a roaring applause. The changed president, still ashamed of his habit, continues to apologize. But he realizes that his error, far from being unwelcome, is instead a reminder of order. He brandishes more bribes as would a child, who, realizing the charm of their ignorance, acts out infancy for treats. Though he is good, he knows injustice is required for good—and that’s all there is to it. Goodbye to all that. He shakes off his morals.

Rats instinctively chitter around a head blooming with ratty thoughts. The creatures start jogging before him, turning back, and beckoning with their pink ears to resume the old order. They cry out, “Here is the cause of the Crime of Having No Entertainment! And here is the solution!”

Many parties then converge at his impromptu podium. It is an overturned refrigerator box, once the home of a loyal supporter. The old man had vacated his premises in order to welcome back the idol. He had upended his home, the last thing he could call his own. For his leader, he would be homeless again, homeless again and again, twice homeless, thrice homeless, homeless to infinity.

The president emerging from below has a beaten quality. His face is like a moral jack-o-lantern, with a radiant good will shining forth behind scars incurred in the rec yard. And behind this good will is another layer, the traces of his former principles, such as they were, “I scratch your back you scratch mine,” “Greed is good,” and “There’s no such thing as society” —so he really resembles a jack-o-lantern with its stiff mixture of fright and warmth. Granting the point that, “At fifty we all have the faces we deserve,” what are we to make of men who, at fifty, have two faces?

The news of the President’s return reach Bobby. It started to rumble and even smoke—it made him jump up and click his heels together from fright, and the smoke billowed over his brain. The shape of smoke and the fires’ new black form caused panic but quickly drive a new ease. Bobby eats in a veritable haze of smoke and radiates into the crowd a feeling of hazy possibility.

The glass house had been so faintly bringing nothing to their homes and hovels—now it grew brighter and brighter. The soul-fire rose in intensity, growing bright and rosy in its hearth. Bobby compiles questions: “How’s your time changed you? Where’d you get those scars? Is it all prison, in and out?” The sleeping commentariat begins to rise at the smelling-salt of fresh scandal. They do not mention how the “president of hope” had sent so many to die, either in oil wars or homicide and insanity, deaths from despair and deaths from crashes on dead and black highways—state troopers gathered around them like vultures, to rescue or observe their decline, the burnt Chevies of the shared spirit coruscating in siren-light, gleaming like the blood of captured prey!

“But some things,” Bobby says, his wit revived and freshly mint-scented, “some things are better kept away from the dinner table.”

He starts speaking again, quickly and in dulcet tones:

“Our president has left prison. His sins cling to his person. But you can take those rosy cheeks to the bank. His speech will be good.

His speech will be better.

I’d rekindle the past if I read from Joe’s letter.

Better make of ourselves the cheifest forgetters!”

The power of rhyme drowns out reason—the newsboys who had jibed the president instinctively switch over to their old provider. They chant the new song “Chief Forgetter.” Their song travels to the president’s ears as he gathers himself to speak before his wet and crumbling stand. Bobby strains to begin again the effort of memory—he twirls around his house in deliberate ecstasy, rising higher and higher off breast photos and car photos. The train-wreck of images and presidential announcements, now blaring like a ticker along the baseboards of his conscience, enable the precious destruction of time.

The song begins to work on Joe the Detective. Even as it works on him he tries to stave it away. He starts to forget just like the crowd. “And it’s my own damn fault!,” he cries, recalling how he had burned the evidence, once pointed against the president, to light his insolent cigar. The little fat man stares at him, menacing, inviting, beckoning, “Smoke me! smoke me!” And his memory, fogged by eon upon eon of loss, threatens to condense to a fog denser still.

“Fog thickened is smoke,” he says—and “A map will not serve you in a world of smoke.” He discards his last black, red cigar. His adversary the cigar, and his adversary, the president, and his double, the Newsman, stare down the little burning stub. The president stoops down to return the Cuban.

He asks: “Why not take a puff, old friend? Why not smoke that old cigar called forgiving?” But, having no forgiving cigars left to smoke (at the time, there was an embargo), Joe puffed away on forgetting. His smoke flowed a lavish darkness upon his soul.

His soul recoiled, as one does from smoking after a long break. But in time it begins to look more contented and began to long for more. And that’s how it is, isn’t it?

Turning in the thick obscurity into a soul of practical kindness, and even a soul that accepts the way things are, it reposed in a vision of hands-off acceptance. In desperation, his private cone of rain tries to dampen his comfort. It dampens the lit end of the cigar—even as it does so, more smoke coddles his soul. The crowd gathers around him to cheer on forgetting’s victory over vigilance—bookies accept illegal bets on the two spiritual prize-fighters.

Meanwhile the president speaks, saying too quickly to hear, “Ladies and gentlemen, girlies, the man in the moooon, the Coca Cola bears, the Energizer bunny (and so on)…I’ve found purpose and you can too. I saw myself also and didn’t like what I saw, I made myself better, I saw good men betrayed, my own feelings, my own, I lost twenty pounds using a new book called the Bible, the Bible says “I’m back baby,” and I can read the writing on the wall and I have a dream, and the name of that dream is: “Freedom is what you want, when you need it.” Freedom is impossible where jail is only inside us. I’m a prison-abolitionist of the shackles called memory, of the shackles of conscience, and I won’t apologize, no I won’t, for all my crimes, crimes without end, Amen.”

His words stir up leaves and water. The smoke from America’s soul leaps from its hearth in Bobby’s home out into the open. The fire from various blazing cigars and the other remaining public goods flies up into the air, and Joe the Detective and Bobby the Newsman see the same conflagration and make the same announcement with different intentions:

They say: “A wind is blowing from paradise…”