Sanibel Island (year-round population ~2,500) is a barrier island off the coast of Southwest Florida, near Fort Myers. Prior to colonization it was home to a people the Spanish called the Calusa. They had a complex social structure, controlling most of South Florida despite forgoing agriculture in favor of fishing and hunting. They made ingenious use of shells for tools, utensils and jewelry until the mid-Eighteenth century, when their society was erased completely in the warfare and disease brought by the colonists.

The island was settled intermittently and informally throughout the Spanish period, followed by a short-lived formal settlement by the Florida Peninsular Land Company in 1832 (evacuated during the Second Seminole War), more stable settlement after the Homestead Act in 1864, and the construction of a lighthouse in 1884. A small, segregated population of Black and white farmers grew tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, squash, cucumbers, and watermelon until a series of hurricanes in the 1920s essentially ruined agriculture on the island. Population fell to about 90 and development efforts shifted to tourism and sport-fishing.

These failed to take off until the 1960s, when tourism boomed with the opening of the Sanibel Causeway. Around this time, the old Bailey General Store relocated and the original building became the Red Pelican, a “hippie store.” The City of Sanibel was incorporated in 1974, spurred partially by efforts to protect against overdevelopment. No chain restaurants are allowed, except a Subway and a Dairy Queen which predated the ban. In 1976 the J. N. "Ding" Darling National Wildlife Refuge was established thanks to the efforts of the eminent cartoonist and conservationist for which it is named. It protects one of the largest undeveloped mangrove ecosystems in the world. The island is very bike-able and, lately, full of iguanas. Its population is 98% white and about 50% over the age of 65 as of 2010.

In the late 1990s, soon after getting married, my parents began visiting Sanibel Island yearly. They stayed at a resort with a Spanish name, with bumpy stucco walls. After I was born, my Dad would load me into the carrier seat on the back of his bike and take me for rides through the nature reserve trails. Sometimes we would see an alligator, and he would worry that it would eat me. After, we’d get breakfast at a place with good scrambled eggs and I was happy to have time just me and him. The path I remember best is through the Bailey Tract, originally owned by Frank P. Bailey, whose descendants own Bailey’s grocery store, successor to the original 19th century Bailey General Store. From when I was around ten through my early teens I would bike to Baileys with friends I met on the island—they always visited the same week as my family—and we’d buy ice cream and rent DVDs. One night me and one of them, a girl a bit older than me, snuck off from the rest of the group and went walking on the beach. We sat and looked at the stars and I was very nervous and thought we would kiss, but we didn’t. I was enamored with her wrestling skills and talent for catching lizards (mostly Six-line Racerunners, I think). She’d put them in little containers with leaves and eventually let them go. We walked back from the beach and her mom and brother were brusque and strange. Next year they visited a different week than us. Or maybe it was a year or two after that. Sometimes I see them on facebook.

I visited Sanibel this year for the first time in several years. My parents recently divorced, so this time it was just my Dad, my sisters, and me. I spent the week with my head full of memories like styrofoam packing peanuts, spiritually congested, preoccupied with the past but unable to feel it. This wasn’t a terrible thing. I was glad to be back; when my dad invited me on the trip I accepted without hesitation. But the immediacy of stucco, lizards, sand, seemed to force the memories attached to them deeper out of reach even as it conjured them up. It was this obscure blockage that drew me to visit the Sanibel Historical Museum with my sisters one afternoon late in the trip.

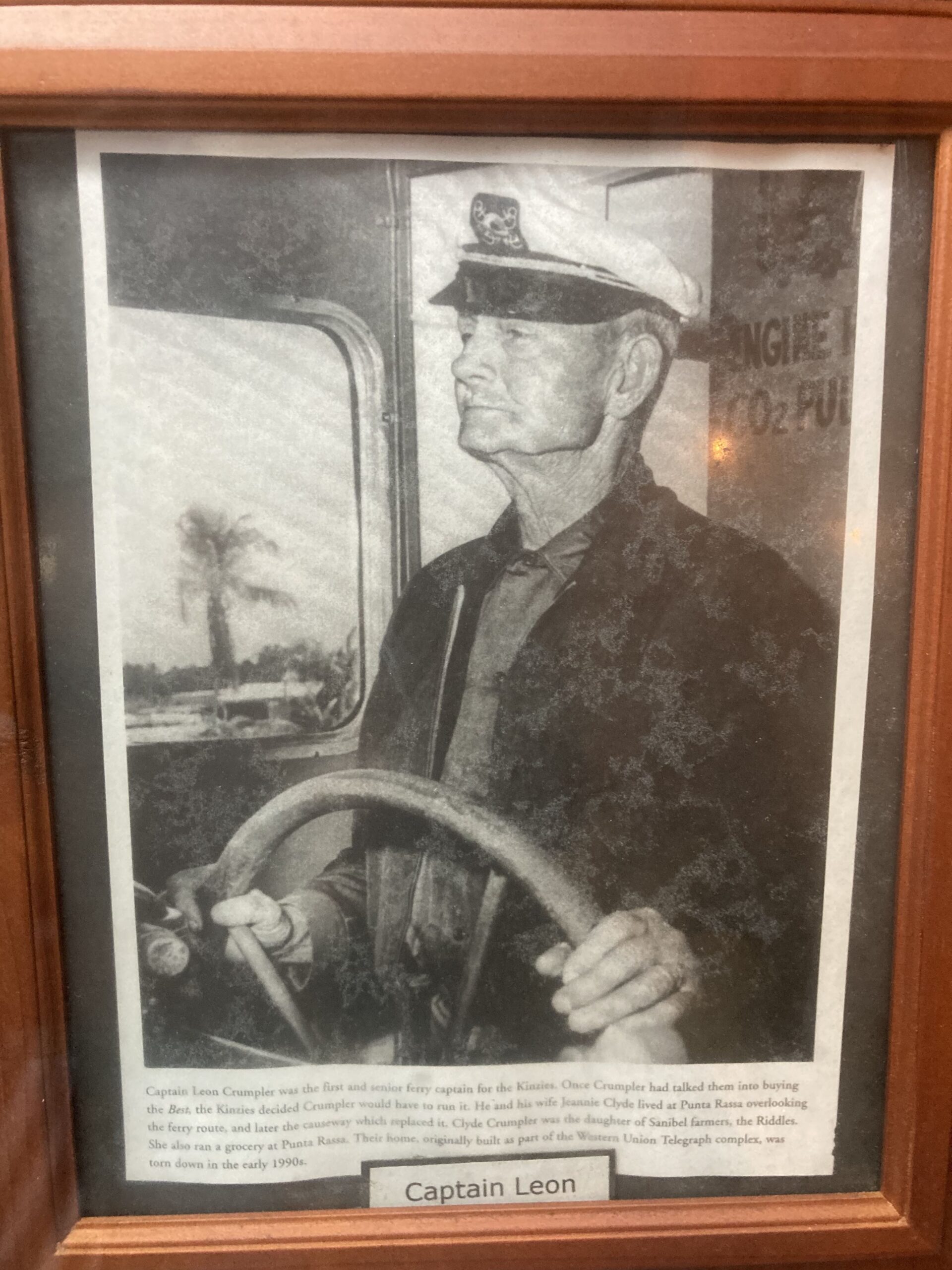

The museum consists of several reconstructed historical buildings connected by gravel pathways. I’d been once years before when it and I were both much smaller. Now there were plaques and wax mannequins and old cars and guides—elderly volunteers who seemed surprised and a bit suspicious of us, probably 40 years younger than their usual visitors. Nevertheless they were friendly and welcoming, albeit in the mildly crabby style of the elderly. One of them—who, it turned out, had been a neighbor of our mother when she was growing up in Iowa in the ‘60s—told us with no small excitement that island royalty happened to also be visiting the museum at the moment, a great niece in one of the first white families to settle the island. We milled around a house that had been ordered from a Sears catalog in 1925 and shipped to the island in 30,000 pieces which fell off the barge just off the coast and had to be recovered, piece by piece, from the gulf. For the move to the museum site, it was disassembled and rebuilt again entirely by volunteers. Inside, informative placards on inkjet-printed, scissor-cut sheets sat alongside old articles about Sears prefab homes and Sanibel in the 1920s, carefully laminated and collected in three-ring binders. In the Caretaker’s Cottage a laptop played a loop of interviews with some of the island’s early Black residents telling stories about the hurricanes of the ‘20s, making dinner with the canned goods they were able to fish out of the flooded first floor of their home.

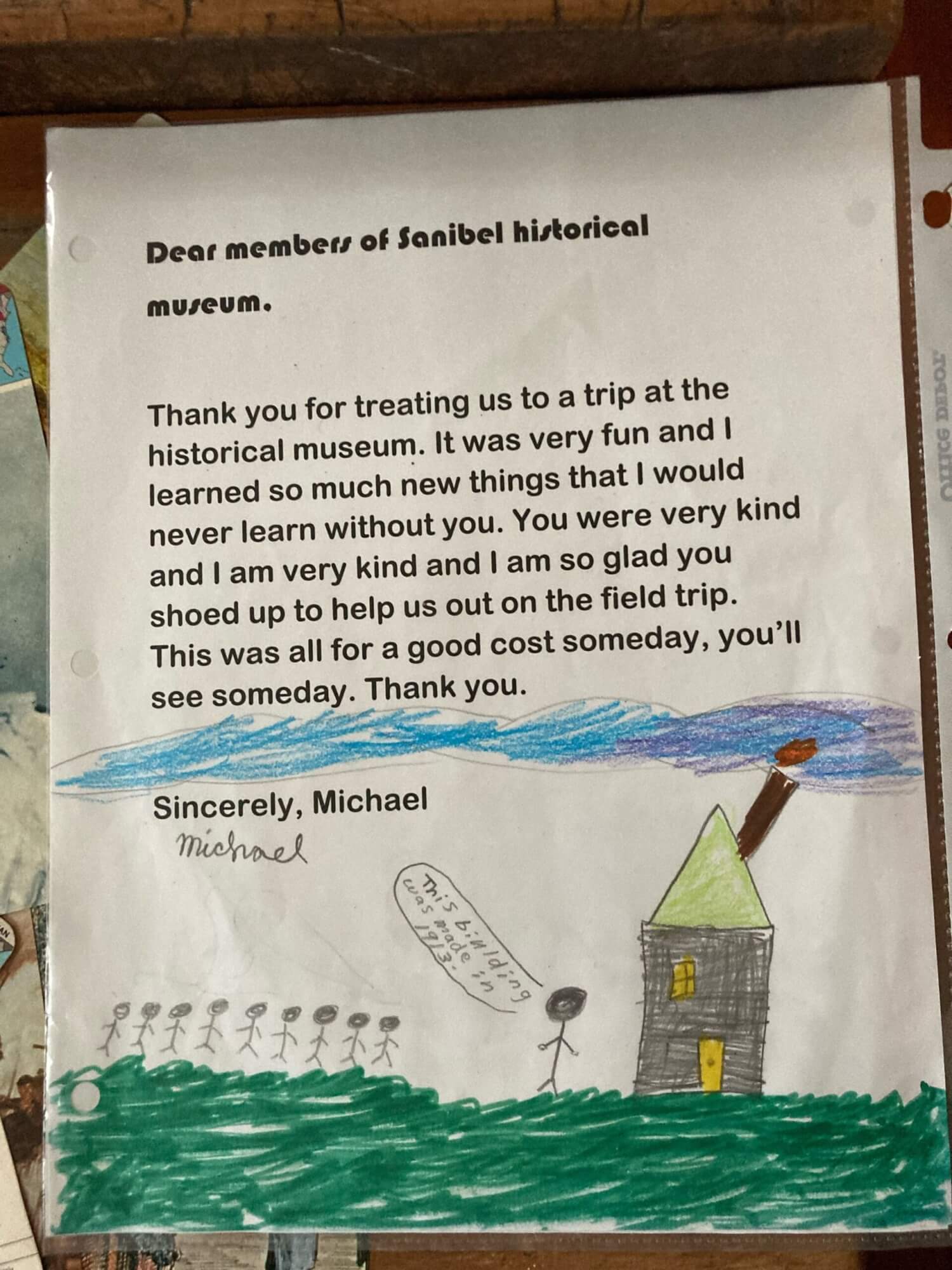

It began to rain and we sheltered in a recreation of the original Bailey General Store, complete with a section on its life as the Red Pelican, “hippie clothes” and all. I wondered about the money and work that went into this museum. Was it the nostalgia, maybe the vanity, of “island royals” like the Baileys or the visiting niece? That helped explain the recent upgrades but felt inadequate to the enthusiasm of the guides, the volunteer construction work, the meticulous printouts. One of the last buildings we visited was the “Sanibel Schoolhouse for White Children (1896).” We rushed through—the guides were already closing up for the day and we’d begun to overstay our welcome, though they wouldn’t tell us so outright. The schoolhouse (larger than those you’d find in the North, since heating wasn’t a problem) was full of old toys and games from the 19th century, as well as notes written by contemporary kids visiting from the Sanibel Elementary School. As we were leaving, one caught my eye:

“Dear members of the Sanibel Historical Museum, Thank you for treating us to a trip at the historical museum. It was very fun and I learned so much new things that I would never learn without you. You were very kind and I am very kind and I am so glad you shoed up to help us out on the field trip. This was all for a good cost someday, you’ll see someday. Thank you.”