Between May 5 and October 31, 1889, Paris welcomed thirty-two million visitors to the Universal Exposition, featuring exhibitions from over forty countries and territories in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and the French Colonies. Commemorating the centennial of the French Revolution under the Third Republic, the expo was the largest and most successful yet hosted by the capital. It was also a touchstone of early modernism, between its inauguration of the Eiffel Tower, public demonstrations of Otis Elevator’s new passenger lifts, and displays of Indigenous and traditional foreign cultures that influenced modernist artists, architects, and composers.

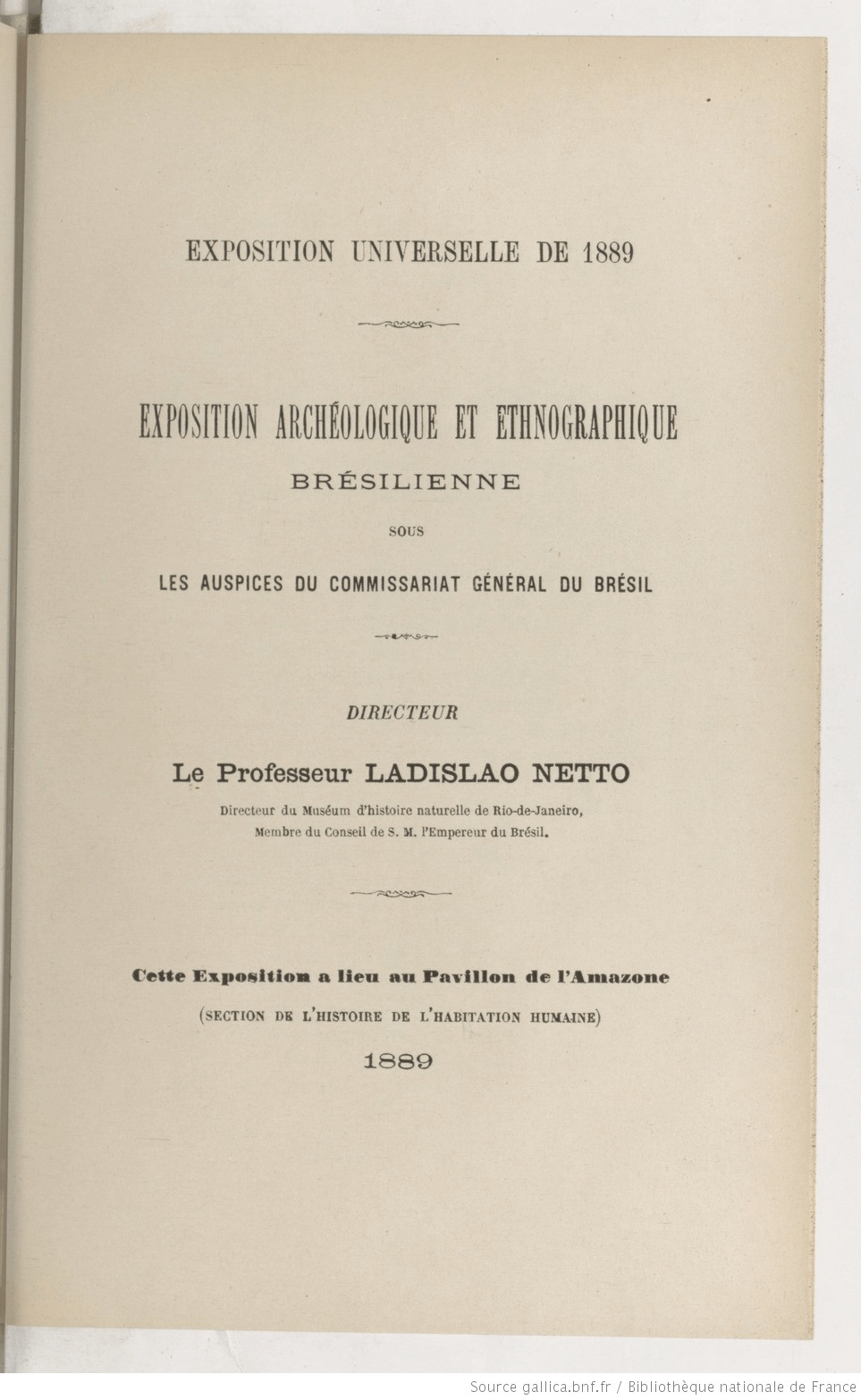

Brazil, along with several Latin American countries, participated with exuberant displays, seeking to present itself as a resource-rich, industrializing nation with a scientific grasp of its natural and anthropological patrimonies. As the last American monarchy, the country was one of few such regimes to participate in the fair—many European countries abstained, frightened by the centennial’s revolutionary symbolism. Still, King Dom Pedro II was enthusiastic about the fair. It was to be the Empire’s last public spectacle: on November 15, 1889, days after the closing of the fair, a military coup toppled the monarchy and established the first Brazilian Republic.

That spectacle was lavishly documented in a special album (pictured here) containing catalogue listings and photographs. Through the quintessentially modern medium of photography, the Empire presented its achievements to a select audience back home and preserved them for posterity. The portfolio, which can be seen in full in the National Library’s Brasiliana Fotográfica collection, bears that distinct air of outdated newness that marks so much nineteenth century boosterist media: the free-standing machines framed almost like aesthetic objects, the overstuffed cabinets signifying a bounty of resources, the wooden typography in a few too many typefaces. It is a relic of the Brazilian state’s voice and gaze in a transitional moment and a record of a historically specific, and sometimes strange, vision of modernity.

Embossed leather

39 x 28 cm

Arquivo Nacional

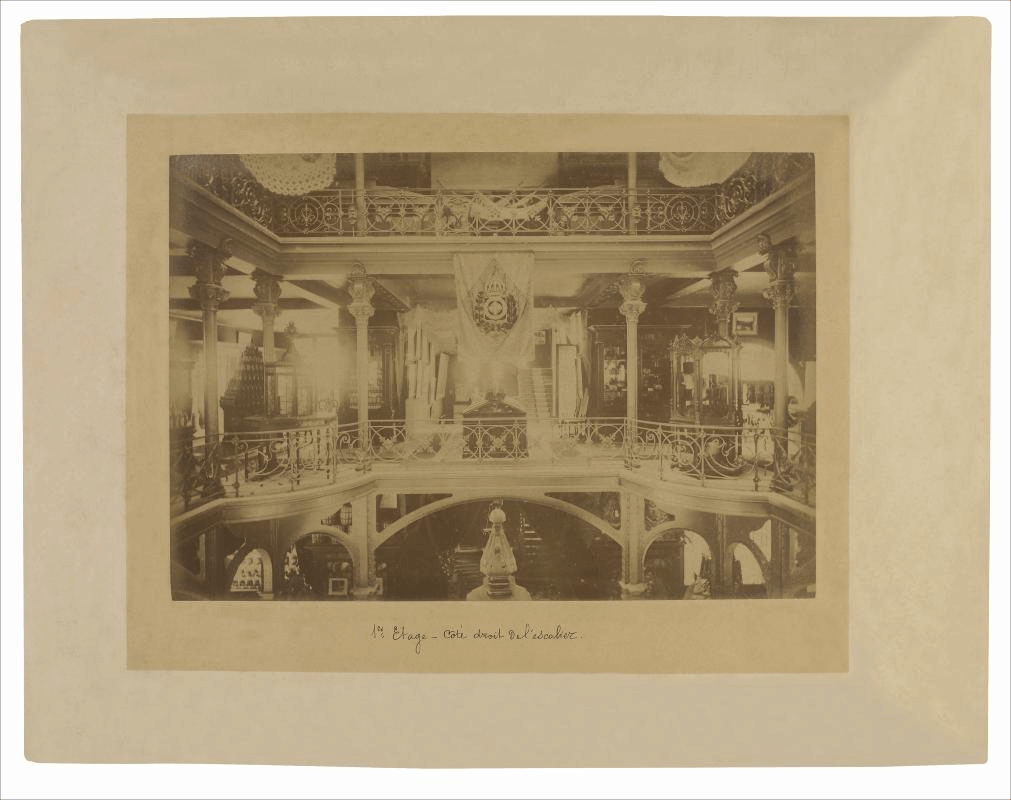

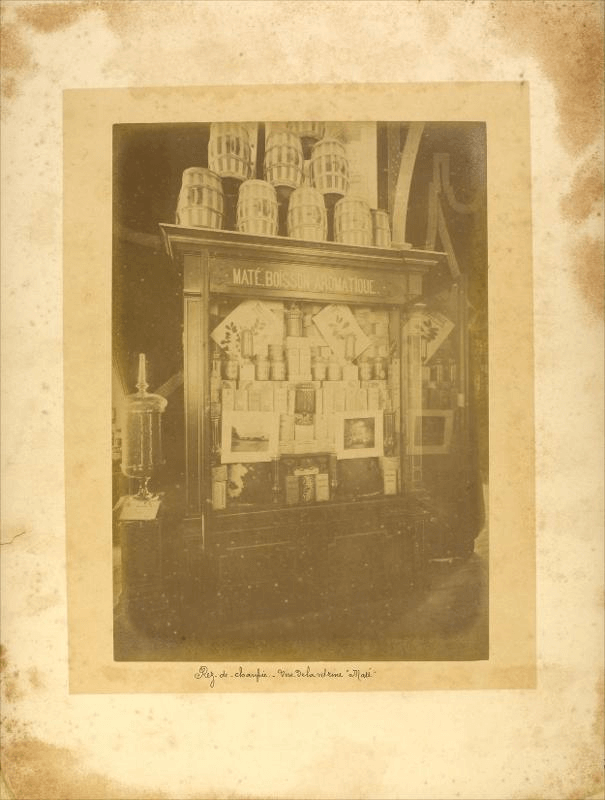

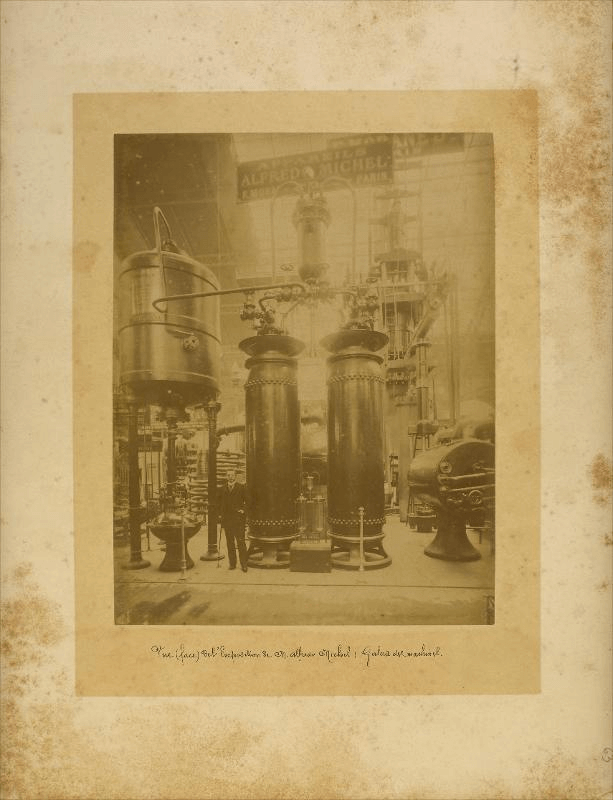

The pavilion of the Brazilian Empire at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris presented a narrative of progessive ascension, moving from a showcase of the country’s natural resources up to its manufactured products, the fruits of industrialization. The ground floor displayed agricultural products such as coffee, tobacco and mate, and extractive resources such as mineral and wood samples. Above, on the first floor, these primary materials were transformed into pharmaceutical products, textiles and clothing, liquors and delicacies, and electrical machines. The second and final floor showcased products of a more sophisticated material culture, including engravings, books, refined ceramics and glassware, medals, and artistic furniture.

Albumen print on paper

21 X 17 cm in 39 X 28 cm album

Arquivo Nacional

Visitors could also enjoy more experiential displays: a coffee tasting booth, a tropical greenhouse, and a pond populated with Victoria amazonica water lilies. In the Machines Gallery, Brazil was represented by a collection of agricultural equipment loaned by businessman Alfredo Michel. Elsewhere, a special Amazonas pavilion displayed traditional craftwork of the northern Brazilian territory, introduced as part of the “isolated civilizations” section in architect Charles Garnier’s imaginative (and somewhat bizarre) “History of Habitation” exhibition.

The exhibition reflected the work of Brazil’s natural history museums and scientific institutions, then engaged in a process of reorganization around increasingly specialized disciplines and the principle of evolution — as were their European counterparts. This ordered articulation of nature and history was both the epistemological foundation and the visual representation of a new kind of modern state that was “but one option among others” in late nineteenth century Brazil. The museum produced and represented new forms of knowledge that catalogued and distributed human and natural resources in the national territory, allowing these resources to be imagined, valued, and managed in the intertwined systems of capitalism and state power.

It is hard to tell from the array of objects on view how up-to-date Brazil would have seemed to contemporaneous international viewers. For some visitors, the picturesque architecture, exotic gardens, and agricultural portfolios on display confirmed the country’s public image as “a great plantation.” For later commentators, the emphasis on natural resources and exuberant vegetative displays in the “alée du soleil”, as the strip of Latin American pavilions was known, reinforced stereotypes in the eyes of an international audience “predisposed to receive and amplify a caricature of Carnival revolutions and carton-pâté dictatorships”. Yet those displays did produce an accurate statement of Brazil’s role in the modern global economy: lacking a self-sufficient industrial sector, but acting as a sophisticated commodities exporter with rationalized agriculture and mining; still rooted in a colonial monarchy, but, by the efforts of that same regime, perfectly au courant with international institutions of knowledge. And so did those displays produce a statement of power. The exoticised materials and wares also demonstrated the state’s command over its own territory; the various commercial products also showed off a rich and well-managed material culture. I prefer to see the album through this lens, and allow it to reveal its aspirations of power and to challenge (if subtly) modernity’s Northern identity.

Albumen print on paper

21 X 17 cm in 39 X 28 cm album

Arquivo Nacional

Albumen print on paper

21 X 17 cm in 39 X 28 cm album

Arquivo Nacional

Albumen print on paper

21 X 17 cm in 39 X 28 cm album

Arquivo Nacional

Albumen print on paper

21 X 17 cm in 39 X 28 cm album

Arquivo Nacional

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Albumen print on paper

21 X 17 cm in 39 X 28 cm album

Arquivo Nacional

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The endpaper highlights the end of slavery in Brazil on the previous year. Brazil was the last independent American country to abolish slavery.

References:

Pauline De Tholozany, “The Expositions Universelles in Nineteenth Century Paris”, Brown University Library Center for Digital Scholarship https://library.brown.edu/cds/paris/worldfairs.html

Heloísa Barbuy, “O Brasil vai a Paris em 1889: um lugar na Exposição Universal”, Anais do Museu Paulista (São Paulo, pp. 211-261, v.4 Jan/Dec 1996)

Jens Andermann, The Optic of the State: Visuality and Power in Argentina and Brazil (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007).

Image sources:

Album of the Brazilian Exhibition at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889: Arquivo Nacional, via Portal Brasiliana Fotográfica (available at: http://brasilianafotografica.bn.br/brasiliana/discover?rpp=10&page=1&query=%22exposi%C3%A7%C3%A3o+universal+de+paris%22&group_by=none&etal=0)

Official catalogue of the pavilion of the Brazilian Empire at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889: Bibliothèque Nationale de France (available at: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9736976f/f164.image.double)