EN: In 2020, Mouse ran an essay by Cameron Knox Day, where the author recounts his experience converting to Catholicism following his interest in Weird Catholic Twitter. In “Questioning Cameron Knox Day,” Daniel Ortiz responded with the following essay.

“Your world of Gods and kings, of shrine and state,

Was of the night when hope and fear stood nigher,

Wherein men walked by light of stars and fire

Till man by day stood equal with his fate.”

—From “Two Leaders”, Charles Algernon Swinburne

Cameron Knox Day, striding like a gladiator, tells us he has been an internet Catholic. His sword flashes—brightly—but these are well-worn colossal sands he treads. We ask him: does he know that? I am tempted to say there aren’t internet Catholics in the same way there aren’t Protestant artists. It is better to cease polemics for now. I want to ask Day a few more questions, posed in a spirit of contemptuous charity.

Day tells us “It was even funnier when I decided to leave the church roughly two weeks after fully converting”. The comparative is that it was funny when he converted in the first place. Respondeo: What does Day mean by fully? For an adult to come into the Church, he must participate in a Rite of Christian Initiation, a catechetical period of several months, after which follows his baptism (if previously unbaptized) and his reception of the sacraments of confession, confirmation, and the Eucharist. When Day says two weeks does he mean he went through this process and, two weeks after, apostatized? Does he mean he was beginning RCIA for two weeks and dropped out?

His references to actual contact with Catholic sacraments, liturgies, and prayer (and so on) are sketchy in the essay. Did he pray? Did he receive sacraments? Did he obey a command he did not understand? Did he feel joyful to the point of terror? Did he sacrifice anything for his beliefs? Did he perform spiritual and (as Pope Francis has reminded us) especially corporal works of mercy? Was love—for God and of God for him—a force on him? In what sense was Day ever a Catholic? Can he feel what those of us who have been will feel on hearing him declare himself past a Catholic phase? Or does he think we feel our religion in the same way he feels his hobbies and his Netflix miniseries?

Day tells us “My contemporary liberal social and political commitments made me very much a stranger in the Church’s world when it came to teachings on gender and sexuality.” That those commitments are as hegemonic in their orthodoxy as the Church used to be is clear from his phrasing. “Contemporary” suffices to tell us what they are. Did he consider his liberal social and political commitments might be misguided? Is it easier to believe that you might through the ritual acts of a divinely-instituted priesthood physically consume the flesh, blood, and essence of God? Why did Day find he could accept that and not accept that this same God instituted a more ascetical idea of sex than his society is used to?

It puzzles me that early heretics focused on Christ’s body and modern heretics focus on their own. I pine for the wiry fanaticism of an Arius or an Apollinaris. At least we wouldn’t have to hear that a religion commanding the emptying and death of selfhood—which is what Catholicism asks of all its adherents—stopped short at asking them to temper their erotic pass-times. I am not claiming that the Church’s sexual teachings are easy to follow. I am affirming that they are not difficult to believe. We could gain much by the return of an old type: the sincere Catholic rake. Day has an oriflamme (if he wants it) in Fr. Andrew Wouter, martyred in 1572 and a womanizer before that. His last words “Fornicator I always was; heretic I never was”. Or was Day’s difficulty to do with something else than belief or action? I wish he could tell us.

Day tells us sincere Catholics are cowards. His words are these: “However, it eventually became clear to me that Catholicism was a rigid and cowardly practice (at least if practiced in full accord with Church dogma,) one renunciative of the beauty of the world and its complexity. We are all much too eager to instrumentalize the beautiful Mystery into a set of anxious codes of conduct – this is much easier than sitting with uncertainty.” About this passage I have a set of questions. (I will put aside incidental infelicities in Day’s prose—why a “set of anxious codes of conduct”? One would think the person making the set would be anxious, not the codes, and, anyways, isn’t his point that many of these codes touch on belief as well as “conduct”? That last word, a refugee from Anglophone post-Protestant manners, is absolutely foreign to the Church’s diction of dogma, sin, and obedience).

More seriously: If Day is possessed of clarity (“it…became clear to me”), why does he deny Catholics that same right? His disbelief in the Church and Her claims might be as “rigid” as his idea of those claims themselves. Or what does he mean by “rigid” and how is this quality “renunciative of the beauty of the world and its complexity?” (Does this locution mean “renunciative of the beautiful complexity of the world” or “renunciative of the beauty of the world as well as the complexity of the world”? Perhaps Day felt it would be rigid to write clearly).

Catholicism is a matter of belief and a matter of action. Day’s skepticism, likewise, is a matter of belief and action. What distinguishes them? Day might want to argue that he is a skeptic and merely denies what the Church (rigidly?) affirms. But denial is an affirmation, is it not? That is, is denial an affirmation of something as being untruth or an affirmation of lack of knowledge as to that things untruth or truth? Day insults Catholics—they are cowards. Is cowardice a manner of belief or a manner of action? Is it both? What things are Catholics believing or doing that Day thinks they shouldn’t and wouldn’t if they were braver? What does he want them to believe or do, in relation to the question under discussion—should they be Catholics?

Day several times uses the word “mystery”. What does he mean by this word? Is mystery incompatible with precision? Is mystery wide or narrow? Is it above or below us? Does mystery mean we can give up on affirmation and action? Is mystery a lack of knowledge or a lack of articulation? What does Catholicism believe or articulate that is contrary to mystery?

About Day’s thoughts on social institutions, and the Internet, and the avant-garde, I do not have any questions. I confess I don’t understand them, and I defy anyone (most of all Day) to tell us what the farrago of metaphor at the start of his last paragraph means.

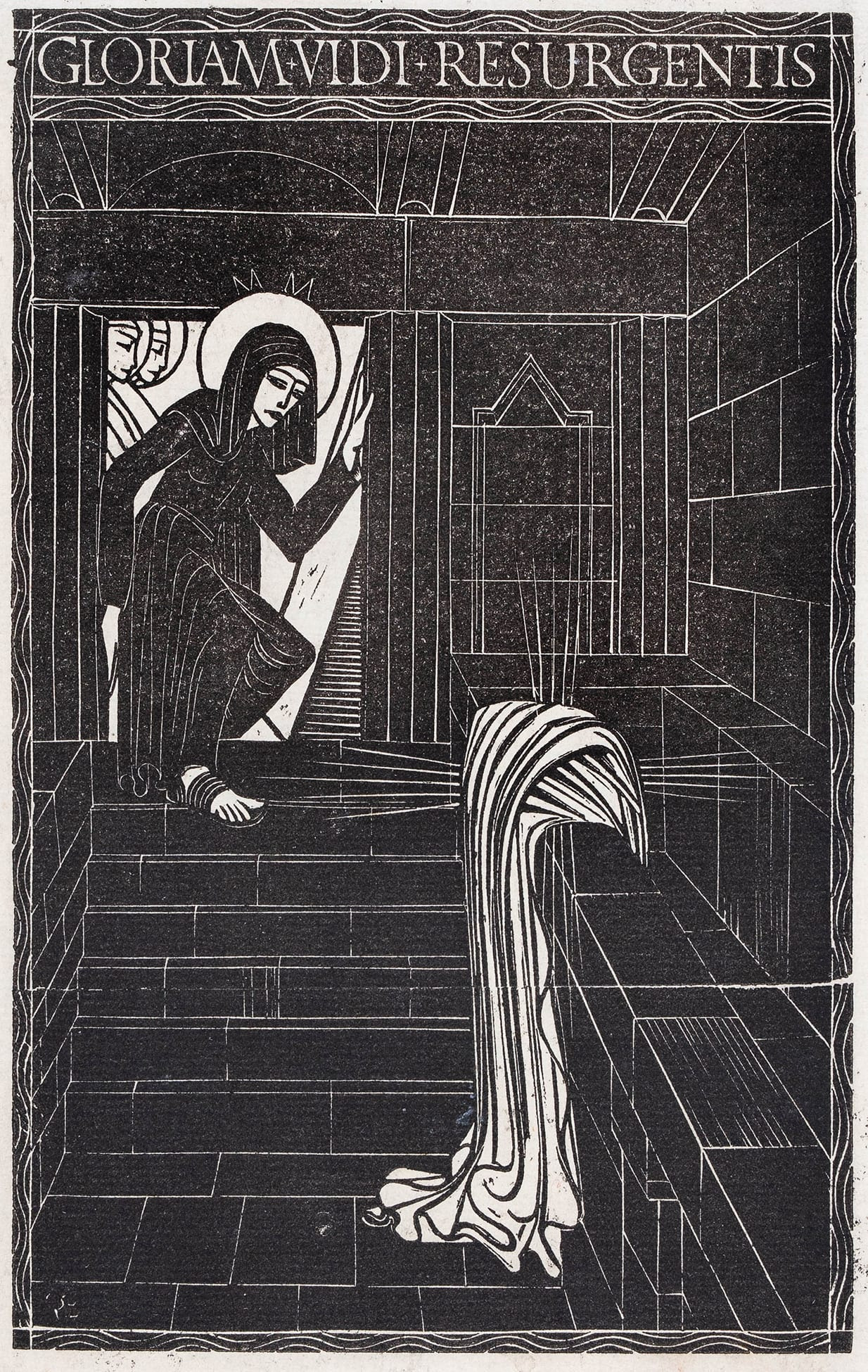

T.E. Hulme, who was not a Catholic, remarks that “It is essential to prove that beauty may be in small, dry things.” Religion, like beauty, can do without the infinite at certain moments, and it is important to recall that Catholicism has always held the right of obscuring as well as enlightening. Day, it seems, wants a religion of sunlight and unfixed definition and (though he wouldn’t phrase it this way) without the type of lacerating questions which now and then drive men to martyrdom. As Swinburne knew, Catholicism is a religion of stars and fire—I mean it is a religion of hard fixed points of light and of a burning love, and it covers itself with benign and unaffected darkness.

Day at the end of his essay talks about a “search”. For what he doesn’t specify. If he is still searching he could consider if his two week flirtation with the Bride of Christ had more to do with certainty than he thought it might have. I will be praying for him.