In 1621, James Howell, historian, watched a Venetian artisan melt salt and sand into translucent glass. As the mixture bubbled, he saw the destiny of the Earth: “If this small furnace-fire hath virtue to convert such a small lump of dark dust and sand into such a precious clear body as crystal, surely that grand universal fire which shall happen at the day of judgement, may by its violent ardour vitrify and turn to one lump of crystal the whole body of the earth.”

If Howell had been in the New Mexico desert three hundred years later, he could have seen his vision come true. When the world’s first nuclear bomb detonated, it turned the sand for half a mile around into glittering jade glass. Chunks of earth thrown up into the air came down again wrapped in shells of green glass, like eggs. Later, shards of the glass were turned into jewelry; actresses wore hairpins topped with radioactive trinitite in an effort to discredit the stories of a lingering sickness afflicting the survivors of Hiroshima. The stories, of course, were true; and on the beaches of Hiroshima, you can still find droplets of glass with pieces of the vaporized city—concrete, rubber, steel—in their hearts.

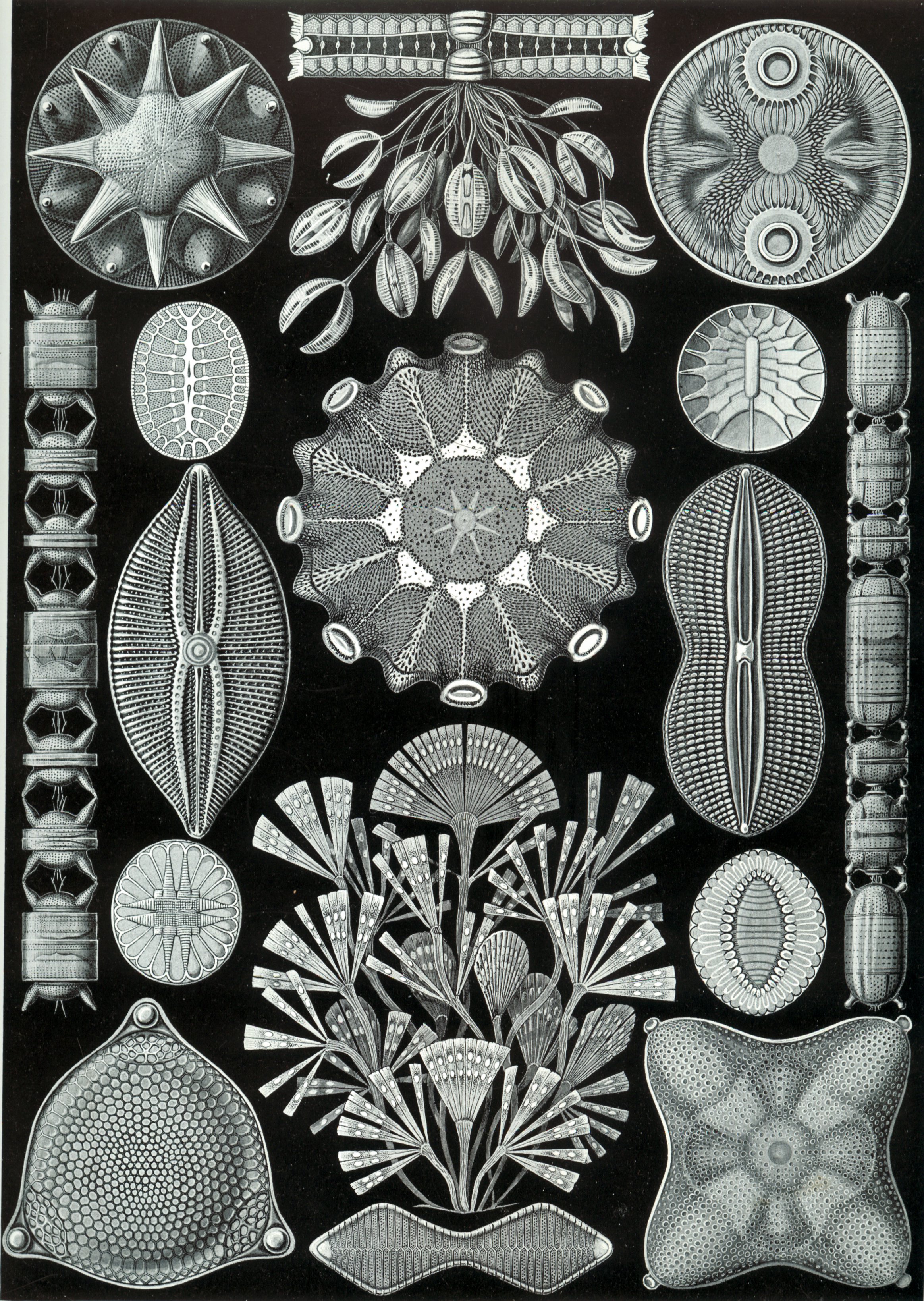

Glass is what happens when a substance is melted in one instant and cooled in the next, before slow-growing crystals have the chance to form. It is the imprint of violence. Lightning, striking a beach, riddles the sand with glass tubes in the shape of its forked fingers. Hawaiian volcanoes sometimes rain down golden glass needles called “Pele’s hair.” There is a part of the Great Sand Sea in Libya where the desert gives way to pebbles of honey-gold glass, melted by a meteorite twenty-six million years ago.

The asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs sent molten glass pouring from the sky like rain. Fish swimming below sucked the glass into their gills instead of water. If you dig down far enough in the right place, you can still find the remnants of this storm: little glass pebbles peppering the layers of sediment.

We are not exempt from these transformations. While he was buried in Vesuvius’ blazing ash, one Pompeiian’s brain melted and turned into black glass inside his skull.

What he suffered in body, others suffered in spirit. Early modern medical texts are peppered with stories of Glass Men, people convinced they had been vitrified. It was one of the innumerable breeds of melancholia: in the medical understanding of the day, when the black bile in your body overheated, you might begin to feel transparent, breakable, and luminous, to see the sun through your palms and your heart through your chest, and to tread softly for fear of shattering.

The affliction took many forms: one man refused to sit down, afraid he’d shatter his buttocks; another tried to fling himself into a kiln, in hopes of being remade as a goblet. There was an academic who believed the ground was a thin skin of glass over a pit of snakes, a king who wore clothes reinforced with iron rods to protect himself from cracking, and a princess who walked carefully, carefully, because she had swallowed a glass grand piano as a child.

It was a disease of scholars, lovers, and poets. To be glass was to be fragile, sharp, and brilliant. Cervantes wrote a story about a “glass graduate” whose malady made him a genius: “He exhorted every one to speak to him from a great distance; declaring that on this condition they might ask him what they pleased, and that he could reply with all the more effect, now he was a man of glass and not of flesh and bones, since glass, being a substance of more delicate subtlety, permits the soul to act with more promptitude and efficacy than it can be expected to do in the heavier body formed of mere earth.”

Dust to dust is the usual way, but sometimes dust takes a detour, becomes crystal. A blaze, quickly extinguished, and the dark earth melts into translucency. The glass in your window is made from sand and soda ash: the white quartz crystals that, over billions of years, are ground away from mountains of weathered granite, paired with the ash of brine-loving plants, glassworts and seaweeds, whose charred remnants taste like the sea they sink their roots in. The beach and the brine melt together to make something as clear as water.

To medievals, glass partook of the nature of the Virgin Mary, because it allows the light of God to pass through it without shattering:

“God is he that iboren was,

Withoute eurich senful likinge,

Of the, ase sonne thorgh glas

Schineth withoute ani brekinge.”

They were right. It is a miracle. We are indoors, yet daylight surrounds us. Let us pray.