Chapter 1: Nietzsche and the Angels

These are my notes from nine months in Moscow, teaching creative writing and theater to people transitioning to life after prison. I also taught literature to men and women in a homeless shelter called Noah’s Home of Industriousness, run by the Russian Orthodox Church. The people at the shelter were not allowed to leave its premises for more than one hour a day, except on Sundays. I sent these notes over email over the course of my time in Russia in order to avoid government censorship. I also wanted to try to stop censoring myself.

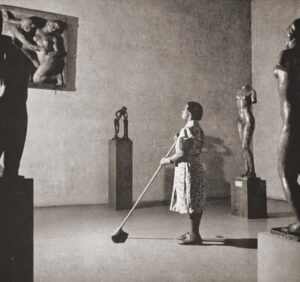

Every time, before I go into the shelter, I take a deep breath. This is my last taste of fresh air before two hours breathing the smell of cleaning solution that poorly masks sweat and stale cooking and human bodies trapped in a four room apartment in which the windows have been closed for far too long. A moment later, I hate myself for having this thought. But I can never stop it from coming into my mind.

Window panes covered with iron grilles that might have been decorative, except for the fact that they are nailed onto none of the other apartments’ windows. Their diagonal design doesn’t fool me. These are prison bars.

Three steps up to the apartment beer store. Odd glance from the woman at the cash register. White button of the unmarked doorbell on the left. The guard in lets me in. I can’t help staring at the graying hair on his chest visible between his suspenders. Unlike the people who live here, I am allowed to enter without a breathalyzer. Entering a dry shelter through shelves of beer.

I cough as the cigarette smoke of Yevgeny’s office burns my eyes. He leaves the page of stock trades open on his desktop. A green line in the center of the screen inches forward with a steady beep. His investment increases. “Blessed are the poor” is gone from his bookshelf, replaced by a silent icon of Christ.

“You want me to copy all these?” he asks looking down at the stack of papers in my hands. Nine pairs of eyes follow me into the room with a large table. My students drag in chairs from the bedrooms, trying to hear their own voices over the screeching noise of construction in the adjoining bathroom.

“So why did you want us to read Nietzsche?” I ask Emma, when most of the class has managed to find a seat.

“His ideas of racial supremacy.”

“What?” I gulp.

“The Romanoffs, a German family, ruled over all of the Russians for more than three hundred years.”

“Well… Nietzsche was not actually a German nationalist,” I stammer. “He was misrepresented as one by his sister who paraded him around spouting philosophy from his wheelchair when he was ill and, most people believe, had gone mad. But, in fact, Nietzsche was so critical of nationalism that he even got into a fight with Wagner over it.”

Emma nods knowingly.

“So is there anything else about Nietzsche that interests you?”

“No.”

The hardest part of the class is always writing. “What’s the point?” Elya interrupts as I try to explain the assignment, “Who will listen to us? We have no rights. Talk about how what we’d like to change?” She laughs soundlessly with her mouth, putting her head in her hands. When her eyes meet mine again, my stomach begins to sink and I have to muster every last bit of determination to prevent myself from crying in front on them.

“Don’t you see that nothing will change if you continue to think about yourselves this way?” I look at Emma and then the others, letting my eyes travel around the room. “What you say does matter and it will be read. I can transcribe it for the Department of Public Policy at the Higher School of Economics if you like, so that the students there can discuss your ideas.”

Emma’s chin, which had been bobbing up and down from laughter, grows still. I can tell that she’s listening, even if she doesn’t yet trust me.

“Lady,” she says, turning her head, wrinkles at the edge of her eyes creasing.

“Please just call me Ariella.”

“Ariella what? I want to know your patronymic.”

“It sounds silly. You won’t want to use it.”

“Still. Just tell us.”

At the end of class, Emma meets me in the hallway carrying two large purple sweaters. “Ariella Dzheraldovna, your sweater is covered in fuzz balls. You can’t wear that. Let me give you something you’ll look decent in,” she says placing the woolen mass into my arms. “I’m sorry by the way.”

Emma never let me transcribe her words for the Higher School of Economics. But at the end of every class after that one Emma brought me a sweater. Now I have more sweaters than I know what to do with. They sit in the living room of my apartment in Moscow in huge plastic bags.

“I’m sorry, Ariella Dzheraldovna, but you are cursed for your villainy. Continue in the same vein, you lackeys of a corrupt, criminal, damned police department, you vile cattle!!! God-damned Jewish cattle!!! Inhumans, you have no honor. Sorry, I’m not in judgement, but in reasoning.”

Chapter 2: The Fast

“A lot of activism simplistically explains…” I begin to write when a man approaches me. One of his eyes is clouded and he carries a duffel bag filled with cans.

“What are you reading?” he asks me.

“Leo Tolstoy.”

“Are you preparing for something?”

“No. I’m doing this for me.”

“What are you trying to get into?”

“Nothing. I have already finished university.”

“Who do you work for?”

“The American government.”

“That’s wonderful.” He smiles. “But still, are you preparing for something?”

“No, I am doing this for myself.”

“Am I bothering you?”

“Well… I’d like to finish this thought.”

“Thoughts are very important…God bless you.”

He takes a few steps as if to walk away, pauses, and then returns to the place on the grass where I am still sitting.

“Here. This is good for thoughts,” he says, dropping two rooster-shaped lollipops on the ground next to me.

***

When I came back I couldn’t understand what people were saying, because the language had changed while I was away.

When I come back to Russia, I am also like a person returning from prison. One of them, but still a stranger: I understand Tolstoy perfectly, yet, sometimes, I do not know how to speak. The people here use too many English loan words.

***

“To no matter whom the question may be put in general terms, nobody is of the opinion that any man is innocent, if possessing food himself in abundance and finding someone on his doorstep three part dead from hunger, he brushes past without giving him anything. So it is an eternal obligation toward the human being not to let him suffer from hunger when one has a chance of coming to his assistance.”

— Simone Weil, The Need for Roots

I hate injustice. (Especially when it happens to me.)

Chapter 3: Twelve Tampons

She said that her nephew was unjustly convicted of murder. He got ten years. It would have been more if he was guilty. According to her, the evidence hung on the tampons the actual murderer used to soak up the blood of the woman as she lay in his apartment in order to hide its trace. Her nephew was convicted, because he was developmentally disabled. And, as a man from Dagestan, he was easy to frame. Perhaps, the tampons could prove his innocence.

For two months I didn’t listen to her, and as I transcribed her story, I treated it as an exercise in creative writing. At the end of my stay, I took her to a human rights lawyer I knew. I suspect that he agreed to hear the story, because I was courteous to him and had donated money to his organization in the past. He said that I could talk to Dmitri, although he was new at the firm and was not sure Dmitri was trustworthy. Dmitri collected all of the documents from the latest stage of the appeal in less than two days. He seemed very interested in the case. He also had a large collection of cognac hidden in a faux book that he continually offered me, and asked me if I was married. He was lonely after his wife’s death.

Dmitri promised that he would work on the case after I had returned to the United States. The problem was that the woman had no money to pay him. She had lent two million rubles to someone named Medea who had promised to help her nephew, but never did. Every week or so Medea would promise to return the two million. And every week the woman seemed to believe Medea’s promises. Dmitri called Medea, in order to pressure her to give the money back to pay for the appeal. I do not know what happened next.

When I returned to Moscow over Christmas break, the woman told me that Dmitri lied to her and had failed to help, like all of the others. She also lost the remaining portion of her money in a Ponzi scheme and went to the human rights law firm to collect the one hundred dollars I had given them on her behalf. They told her that the money was not hers, but mine, and threatened to call the police. Eventually they returned the money to her. By that time, Dmitri no longer worked for the law firm.

The woman gave me a very large box of chocolates in order to express her gratitude and asked me: “You’ll help me to get another lawyer, right?”

***

About a week before I went to Moscow as a Fulbright Fellow, I called her to apologize that I had failed to help. I told her that I would love to see her and to talk to her, but that in the future I would not be able to help her legally.

She said, “Ariella, you have already helped me more than anyone else because you didn’t laugh at me. You were the only person who took me seriously.”

I didn’t call her again.

Part 2 of Notes from the Cave can be found here.