Last summer, I spent three months working at a hotel, tucked away in a valley in Northwest Iceland. My father was born in Southern Iceland, and until then I had only known my connection to Iceland through a name, a passport, and a language.

On the drive to the valley with my aunt and grandmother I was told that the hotel had once been a boarding school. Upon my arrival, I found out that I would be one of the last people to work there; it was set to close for good at the end of August. So, the hotel that once was a boarding school, would soon be known as once having been a hotel. I tried not to think too much of its end during my beginning.

I worked at the front desk. I greeted families, solo travelers, couples who mostly spent their night at the hotel on their way North or further West. The valley had nothing spectacular about it, it was not a place to see waterfalls, glacier lagoons, or geysers. “Is there anything to do around here?” guests would sometimes ask me after their breakfast as they stared, confused by maps displayed on the desk separating us, expecting me to have all the answers. There was a small town 20 minutes south, and another 40 minutes north, and there is a natural hot spring a few meters away, I explained forgivingly. I was also often asked how high the mountains were, their names, and other questions I barely knew the answers to.

I started taking notes in a small notebook of visuals and people, to capture the fleeting days. I thought of myself as an archivist of Summer 2019 at Hótel Edda, Laugar í Sælingsdal. I kept in mind Sophie Calle, who began her artistic career photographing strangers’ belongings when she was working as a maid in a hotel in Venice.

I wrote down my daily tasks and observations as a list, imagining them as photographs:

-I pushed flies out of the window, folded napkins, served beers to 5 Americans

-The driver takes a smoke break, the sheep make a family

-Someone has their entire credit card memorized and she recites it to me

-The lingering smells of perfumes in rooms

After two weeks of working, I discovered a museum in the basement of the swimming pool across from the hotel. There were flyers in the lobby that I hadn’t paid attention to until I met Kendra. She was writing a book on Icelandic museums and had booked one night at the hotel as she traveled back to Reykjavik from the many museums she had researched, such as the Museum of Witchcraft and the Museum of Sea Monsters. I met Kendra and her friend for breakfast, and then we walked around the hotel. Beyond the entrance of the swimming pool and down the stairs we descended into the museum dedicated to the people of this valley.

In Iceland, local museums called Byggðasafn are time capsules of specific locations. Every town has histories and stories recorded and archived. In general, almost everything in Iceland is in a book and has a name: old ships, mountains, farms, houses. Too many to fit on every map. Too many to remember. Óteljandi is a word that signifies when there is too much of something, it translates to “uncountable.” I have heard the word used for scattered islands on the shore, but I imagine there are also hundreds of objects scattered around the museum, uncountable.

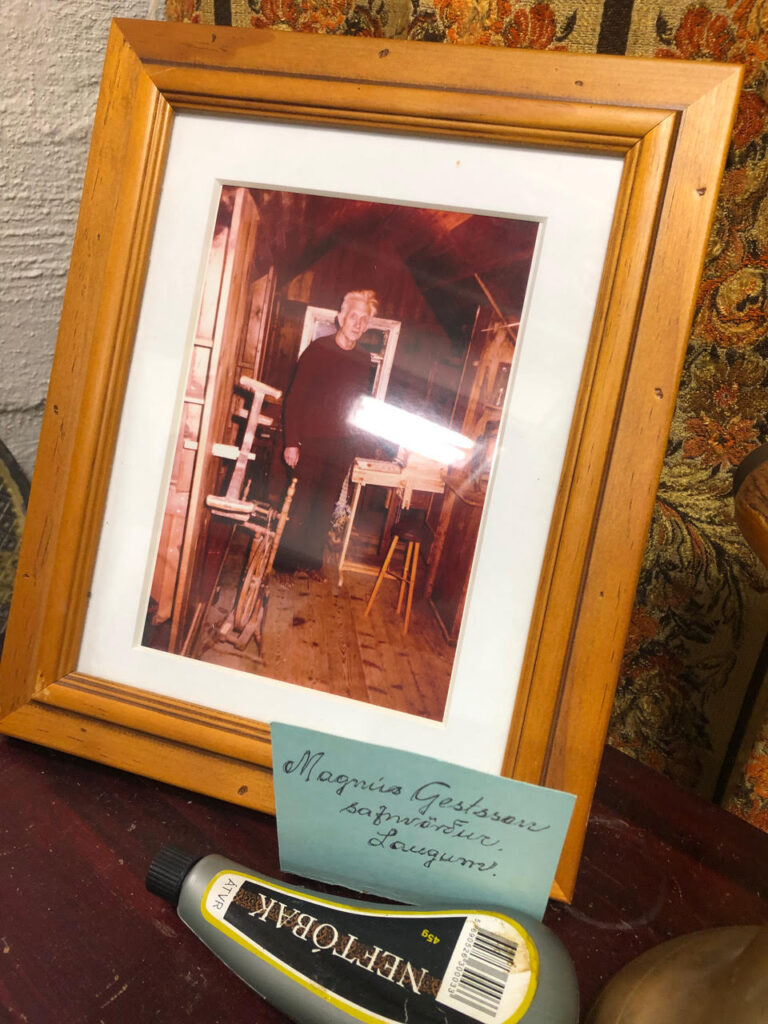

The museum we descended into was crowded but cozy. The woman who greeted us (the owner and collector of all these items) introduced herself. Valdís had long grey hair, which she pulled back into a braid. She wore a traditional lopapeysa (a wool sweater), which I can assume was knitted by herself or someone in her family. She later explained that she was the daughter of a sheep farmer, and so I imagined she maybe knew the sheep from which the wool came from, and even their names.

The museum opened in 1977 and existed before the hotel was a hotel, when it was still a boarding school. Valdís did not always own it, but she seems perfectly suited for being the story teller and speaker for these objects.

She shows us several objects, narrating the history of the ones she finds most exciting. She pulls up a stick and makes us guess its purpose. A thick branch that has been scraped of its trunk skin to reveal the light wood underneath. I notice that its texture is similar to sea glass, the way it’s been softened by water, and that’s when she reveals it was a stick used to stir laundry. She smiles as if savoring the secret knowledge of the stick’s utility. Clothes used to be cleaned in large buckets of boiling water and stirred with wooden sticks, long before washing machines. She thinks if an archaeologist were to find this, they might ignore it, not see its value.

The museum is separated into themes. The laundry stick sits surrounded by other wooden items from the 18th and 19th century. There are taxidermied birds scattered around the museum. A corner for technology, where I find a phonebook from the 1960s. Kitchen objects, sewing and traditional clothing, precious stones, and an entire corner of the museum is dedicated to the remains of a church. It is even set up to mimic entering a church; there is a bell hanging from the ceiling, there is an altar and bibles on chairs. There is even a giant cross, made from two large sticks and painted white. There is also a long turquoise church bench from the 13th century. According to Valdís, it was used not too long ago as a seat in a kitchen. She points to rust on one side, explaining that it was placed near a sink and the water created dents and rust. It had not yet been seen as belonging in a museum. One family had it in their home for decades before realizing its age, its value.

There was also a headstone used to commemorate a horse’s passing, a horse who had drowned in a pond during the winter of 1906. The farmer had placed an enormous rock on a hilltop to commemorate his beloved horse, but it eventually rolled down and cracked in half. Too heavy to be placed anywhere else, it sits on a table in the kitchen part of the museum, to the right of the entrance. I read the Icelandic, “Here lies a horse,” but I could only vaguely decipher the rest of the sentence carved into the stone, picking out the words “drowned” and the name Ólafur Pálmason, the farmer who owned the horse.

Valdís is a collector of the everyday, and her museum is a collection of the mundane, the used, the never polished or conserved or repainted to appear new. She is proud to share that every object has a small story attached to it, which other museum collectors might not be interested in. These objects are, to her, the most beautiful. There are marks and scratches that make them unlike any other. You can narrate something from them, and maybe explain and understand the past.

The hotel is a museum in its own way. The halls filled with class photographs, from the 1940s until the 90s. I enjoyed walking back and forth to examine the hairstyle trends. Beehives, curls, bobs, and mullets. I was confronted, one night, with the complaints of a guest who saw the hotel as “old fashioned and uninviting.” Other mornings, I was delighted to give keys to rooms for old women who whispered to me that they had gone to school here, pointing to their photos in the yearbooks, remembering the exact rooms that had once been their dorms.

One evening, as I was closing up the front desk, Valdís emerged from her basement museum and invited me on a “storytelling walk,” hosted by her and many other locals interested in the stories and histories of the valley. She drove me in her car, it was 50 minutes north, near the beginning of the Westfjords.

I use the word “story” loosely. The Icelandic saga, related to the English “say” and “saw” (as in “old saw,”) means both stories and histories, the real and the fictional, the factual and the mythical.

The winds were strong. I was shivering in my jean jacket. Valdís offered me my pick from the pile of knitted hats in the back of her car, spreading them out like a card dealer. They were all in the same shape, so it wasn’t much of a choice. We walked towards a church with matching knitted pom-pom hats. Mine grey, hers blue.

Inside the church, 39 of us listened to the storyteller of the afternoon. I could hear and feel the wooden structure creaking from the wind. The chandelier above us shivered. I was not fully listening to the story since my attention was turned towards the unstable structure of the church. I could slightly make sense of one story, a man who was hiking and stumbled upon a steep hill amid flat land named Tungustapi.When he climbed to the top, there stood a door he had not previously seen. He opened it onto a mysterious wedding, characteristic in Icelandic folklore of an encounter in the realm of elves.The hill was visible from my hotel room, and sometimes I was tempted to walk towards it in the hopes of an elf party.

After the elf story, we walked outside to the remains of a house. We saw stone outlines, recognizing where doors and walls once existed, as well as a bathtub. One woman knew the names of all flowers and plants. Everyone asked her for more while pointing to the various purples and the yellows sticking out of the archaeological remains.

All wind-swept and tired, we had coffee and cookies inside the church. I ask Valdís about what will happen once the hotel is sold. She’s optimistic about the future of her museum but we barely talk about it anymore. Her objects hold precious life and I am worried about their future.

I start thinking back to the museum in the basement, and what specifically defines a museum. Is it the stories that make the objects have value, or the objects themselves which create the museum? What are the limits of calling a room full of objects a museum or something else, such as these story walks? I start to see them as ephemeral museums themselves, fleeting and floating. Valdís never allowed me to record her speaking, but I accept what my memory holds and what it has lost.

The room I slept in for two months had once been occupied by various strangers going to school, from the 1940s until the 1990s. I, in turn, watched tourists come and go from July until August. I hope whoever owns the building next, the boarding-school-turned-hotel at Laugar í Sælingsdal, will remember its stories.