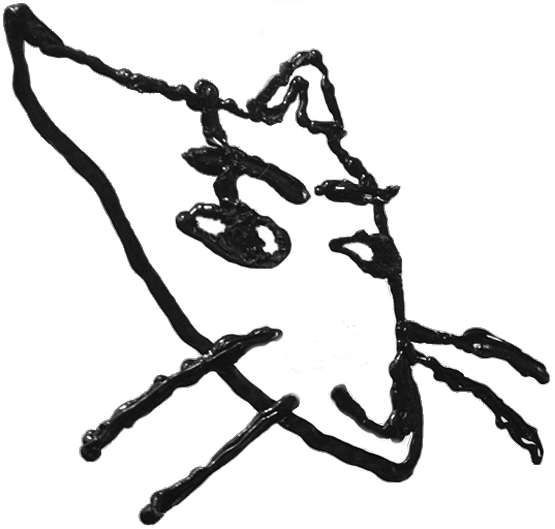

The launeddas is an ancient Sardinian instrument, similar to the bagpipe, consisting of three separate cane flutes played simultaneously. With a circular breathing technique, players use the largest flute (su tumbu) to produce a single droning note, and the two smaller flutes (sa mankosa nanna) for the melody. Each finger hole is called a krai, or key, and the reeds are often altered with wax.

Though flutes come in many different sizes, only certain flutes are paired together, and each pairing has a name and scale associated with it. Some of these are: the thorn, the bagpipe, the median, the median as a little girl, the monk and the nun, the widow, and the marriageable widow. Dialogues take place between the flutes in certain songs: the monk talks to the nun, a lover talks to her beloved. The marriageable widow is an upbeat variation on the widow.

In the past, players made flutes from cane stalks cut on nights of the full moon and hid the best patches from their rivals. The instrument conferred an enviable degree of prestige which allowed the most gifted players to rise above social stations inherited at birth. Though Maestro Efisio Melis’ parents had the “despised occupation of selling wine and nougat at village festivals,” he was able to join elite Fascist circles in Cagliari on account of his gift for “discovering ways of amusing himself and others.”

Melis spoke with the author of the definitive treatise on the launeddas, Dutch anthropologist Andreas Bentzon, who traveled Sardinia on motorbike, transporting his sources’ hay and pecorino in return for the opportunity to record their music. After learning that the anthropologist was to visit his rival Antonio Lara (76 at the time,) Melis lied to Bentzon, saying that Lara had suffered a fit of apoplexy and would not be able to talk. But the trick was only payback for an earlier incident, when Lara had told everyone that Melis was dead, forcing Melis to travel around Campidano Cagliari to prove that he was still alive, and available to play Sunday dances.

Lara recalled his own teacher hiring sentries to prevent him from hearing and then stealing his themes (called noddas in Sardu). Refusing to obey, Lara hid himself behind a stack of kindling in the courtyard of a marriage ceremony, where he heard and then stole his teacher’s noddas.

It was normal for masters to refuse to teach their students—they would say they were “too tired” and “had other things to do.” Sometimes retiring masters taught students only in order to sic the younger player on their rivals. Palmeriu Figgus was stabbed with a knife after winning a launeddas competition, and concerts sometimes evolved into feats of strength, with flutists blowing until one or the other bled from the mouth. Efisio Melis once insulted a rival player with these words: “You are no launeddas player and cannot be one, because you are not from Villaputzu, but from a small village where they do not know what cane is.”

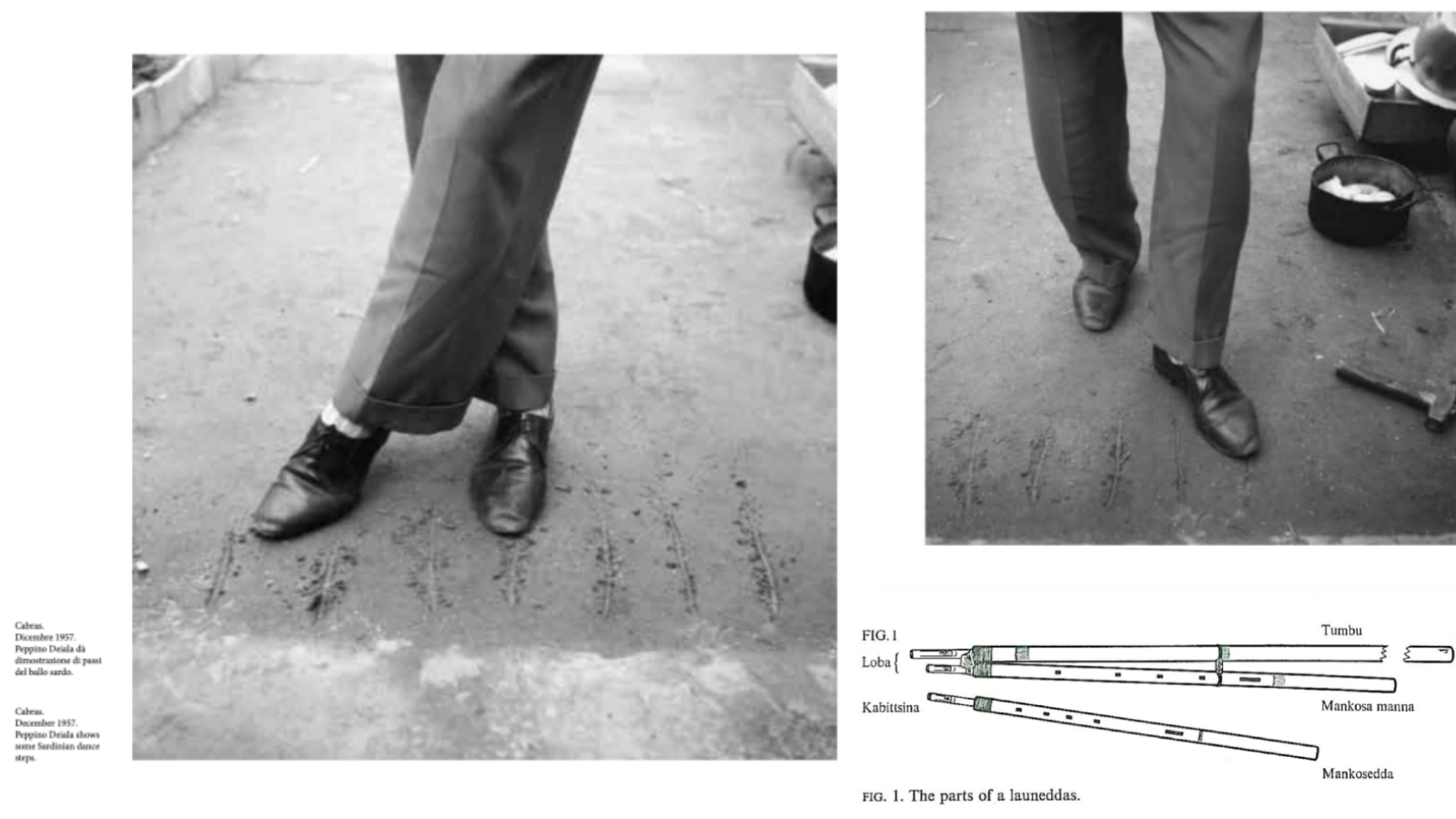

People and generations differed in their sense of how regimented the playing ought to be, how much it should encourage the emotions, how it should induce one or another kind of dancing. Nietzsche’s critique of Wagner—“Gradually one loses one’s footing and one ultimately abandons oneself to the mercy or fury of the elements: one has to swim…”—his advocacy of “old music—where one had to dance,” which act required “control of certain balanced degrees of time and energy, and forced the soul of the listener to continual sobriety of thought”—finds echoes in the preferences of the conservative village of Cabras for Giovanni Pireddu, whose playing “was so firm no one could miss a step”; their dislike of the “undanceable,” excessively fast Efisio Melis; and their exhortation of a serio style of play. Songs were criticized if they “mancano d’argomenti” (lacked a topic); good playing was “piu giustu e piu morale” (more correct and more moral).

Sardinia’s global integration and modernization, and the accompanying influx of other kinds of instruments and music, resulted in the marginization of the launeddas. Today it lives on in religious processions, concerts and folklore festivals observed by tourists. It is sometimes mixed, in my view unsuccessfully, with jazz.

A 2015 documentary with 522 views on YouTube profiles five young launeddas players in Sardinia. “Figli di crisi” (sons of the crisis), the boys have been afforded the time to perfect the difficult cane flutes by periods of prolonged unemployment. Some of them attended the underfunded technical school where I teach, where the internet is always out, and where the maps of the world in every room are crazy tapestries of cocks, hearts, the names of lovers, the names of rappers, and the English word “gay”… And here some students have graffitied the names Sestu, Settimo, and Sinnai over Fijian islands– a joke about how far these provincial towns are from Sardinia’s capital of Cagliari.

Graziano Montisci, one of the young players profiled in the film, teaches circular breathing to aspiring players by having them blow into cups of water with plastic straws. The practice recreates a game played by the sons of shepherds with blades of grass and clay bowls which was also preparation for the launeddas. A Skype student from Sacramento quits his lessons before mastering the requisite skill, a fact which causes Montisci some anger—and the effort to speak optimistically about his own future creates slight, pained modifications in the young man’s voice.

“For someone who plays the launeddas, the right job is crucial,” he says. “If you knead concrete all day your hands will feel it … At home my parents tease me, ‘Oh you’ll ruin your hands! Oh, callus!’ But they don’t know what it means to spend many hours practicing an acciaccatura.” Montisci drives the No. 8 bus to keep his hands soft.

It passes the same train station and churches every day, ascending the hill into Castello, where for a few minutes one sees the city laid out like sets of pots and boxes: the Brotzu hospital, Buon Aria church, and the monumental cemetery; the tennis courts by the communal gardens, the one-and-a-half-story Ferris wheel known as the City Eye, Piazza Yenne full of youth in Emporio Armani. Then, far off, the mountains in Pula, Capoterra, and Sarroch.

Montisci and a young accordion player meet in a Conad grocery store parking lot one night, pour red wine into plastic cups and play a song together. The light from the store signage shines onto their van, while their friends smoke cigarettes and chain dance in the shopping cart depository. Later, they perform at a procession for Saint Efisio, walking ahead of two brown bulls.

Calm as gods, horns garlanded in flowers, the huge, gorgeous animals tow the saint as an old woman in a shawl and her husband in a tracksuit scatter rose petals on the ground. A long line forms behind them, consisting of priests, farmers, pilgrims, cross-bearers, policemen, children, and tractors who pass from the paved roads of the town to dirt roads surrounded by tallgrass.

I once heard launeddas music at a protest in Teulada. A few hundred people had come to demand the closure of the nearby NATO base, which regularly tests bombs in the area, leaving radioactive thorium deposits in the ground. The black bloc tried to run around a line of riot guards while the older activists sat by the pickup truck, playing music and making salami sandwiches. An ancient and grizzled looking man put on punk separatist music and then a launeddas song, which led some people to begin to dance.

Two older women with rich, smoke-damaged voices called to the man and asked him to dance. He smiled and shook his head, but they insisted, taking him by the arm and leading him into the sand. There, with linked arms, the three of them made crosswise steps in and out of a semicircle, throwing their heads back and laughing in joy. The man danced faster and faster and appeared unburdened, as though a bad season had passed. The police loitered by their armored bus and a boy called out from the side of a cliff on the base, where he had placed a smoking orange flare.

In the Sardinian ballu, as in Riverdance, the upper torso is kept rigid while the feet fly—because of which it seems as if the dancer’s spirit is forced up from the fast-moving feet, past the torso and into the head, where it expends itself in involuntary expressions of joy, of freedom born from restraint. A Bronze Age sculpture of a launeddas player captures this unabashedness, with its wide open eyes, its cheeks inflated and full of flutes, and its penis erect.

Launeddas music calls to my mind prelapsarian dreams, with green insects embodied by the drone flute and flocks of sheep embodied by the chanter flutes, all singing encouraging words, telling us to finish our work and then forget it. The songs suggest a harmony in purpose between humans, plants, and animals—a compilation of the shared compositions of rivals Efisio Mellis and Antonio Lara sounds like a field of crickets, whose chaos and order slip into one another with the complicated regularity of ecological cycles.

In their two-part Fiorassiu e puntu e organu, it is as if one were looking at the white and black dots on a static TV screen and suddenly saw rings of dancers and singers emerge, with one or another dot standing alone for a moment to sing out a long note above the honks, drones, and squeaks of the others. Their Fiuda Biugadia is more like a singing, dying motherboard, except that the modular notes (unplaceable on a gradient connecting animal and machine) are interrupted by festive shrieks of laughter and shouts in Sardu. The album is full of wild, violent, and happy songs like these.

So it is not hard to believe that people used to say the launeddas could make you insane, make pregnant women abort, make young girls fall in love, and blow the roofs off of churches. Some also held that there was somewhere a certain charmed instrument with a silver tongue-piece that only chosen players could sound.

Antonio Lara’s memories of the magic player Agostino Vacca seems to recall so much that his account breaks down:

Antonio Lara: They said Agostino Vacca had [a charmed instrument].

Andreas Bentzon: But how did one know?

AL: Oh, but it is something … Oh, until eighteen years old he was a swineherd, then when he was eighteen years old there came somebody who …

AL’s wife: It must have been the hand of God.

AL: But when the launeddas was sounding, it was also as if the earth was trembling … from the energy of the sound. My father tried, and he was a good launeddas player. Gioaniccu Cabras tried. They could not give him so much breath. [AL lifts his little finger.]

AL’s wife: And his instrument …

AL: It was empty, that instrument. They could not give enough breath, they could not breathe in it. It was an empty instrument, they did not succeed. They have thrown it away. But! You could go to jail! And he, he took it … He was only half a man. [AL shows his height.] He played like a … Madonna Santissima!