Filed with the papers of Dr Bridget Ann Weber.

Undated letter, addressed to Bridget Weber c/o Weber Investigative Services in New York City, from a Mrs. Edgar Alexakas.

My dear Birdie,

Even as I begin to compose this letter I know that writing to you is a fool’s errand. It will be a series of miracles if this letter is finished at all, if I post it to you, if it finds its way. And of course you must read it too, another miracle. I’m trying to imagine what you must have thought when you first saw the envelope. Initially, I am sure, a profound lack of recognition at the sender’s name, which I will admit I have done purposely so as to prevent your immediately burning the whole thing unread— tell me, Birdie, do you still find such satisfaction in burning those letters and writings you don’t want to look at any more? I remember sitting around your mother’s stove as you fed your old poetry into it, like feeding table scraps to a begging dog and laughing as his fiery tongue lapped them up. You said you had woken up at night and seen the poems peeking out at you from the trash can and you had known that you must destroy them entirely.

Well by now I’m sure you must know which little old woman is writing you. That is, if you did not from the first line. Or if you did not from some distant thing you felt as you weighed the unopened letter so carefully in your hand. Oh, Birdie! You must believe me that the promise I made to you was made in earnest, and I had no intention to break it the way that I now must. But how could I have known all those years ago about what would happen now? I can see you standing up and crossing to the fire even now, but please, if you could just finish reading, and give a patient minute to my desperation. You must allow me these few pages, at least, to explain myself.

I have moved out to the country after all. I live in a small pretty house with a garden and whitewashed walls and dishes that match each other, all of which I find quite terrible, but I think it makes Hester happy. The house is wreathed in a ludicrous bounty of hydrangeas, and is built on the top of a hill, though not much of one. It’s a rise, I suppose, because the nearest town is called Tamanee Rise and it’s on one too. My rise is very bare except for the house and the garden and then, a long ways off, the forest and the road that cuts through it, which are the only things around for miles. It’s very quiet and peaceful at night here, so it’s hard for me to fall asleep, but I can get by most of the time.

I bought the house with the money that my husband left me. I guess you don’t know about him, though you’re probably wondering why I’ve put his name on this letter. There’s too much to say here, and it doesn’t have much to do with what’s happened, but I suppose you should know that I was indeed married and he’s dead now about ten years. At any rate the money he left me was enough for me to buy this little house on the rise and to pay for someone to buy all the furniture and pans and wallpaper and things which I thought I wouldn’t care about but looking back I wish I could have chosen for myself. I hate the little silverware organizer in the kitchen drawer because I can never find anything, and when the moonlight comes in the rooms at night all the furniture looks like animals, and of course there’s Hester’s cold spots and hot spots and the broken things. But I think I really could have been happy here. Maybe I still can be.

We are on the verso already, and I must come to the point. Last night, I woke up at close to three. I sleep with my covers untucked like I always have, even though it means I usually wake up to the sheets strangling me and the bedspread kicked down onto my room’s beautiful hardwood floor. I don’t particularly like the floor because the boards are always so cold against my feet in the morning.

Last night when I woke up, however, it was very warm, and I was tucked into my bed as tightly as a baby swaddled by an overzealous mother. With a huge effort I managed to extract my arms, and one of them touched a wall close by, as if my bed had been pushed to the side of the room while I was sleeping. And then I reached out my other arm and it touched a wall on the other side, and I realized the room I was in was far too small to be my normal bedroom, even though the horrible wallpaper with its tasteful blue flower pattern was still there on the walls.

The window at my feet was the same shape as the sash windows in my room but in the wrong place, and as I managed to sit up and push the blankets down to my waist I suddenly couldn’t look at it any more because it seemed like the sun itself was right outside. I turned my head away and watched the rectangle of light falling on the bedspread grow brighter and brighter and the shadow of the sash bar slowly thin away as the light grew so bright that no shadow could withstand it. The air of the room was getting very, very hot, so hot that my skin hurt and I was surprised it didn’t burn, and I called out once for Hester but she didn’t hear me or couldn’t answer. All the colors of the things in my room were turned very strange. It was not my room. It was my room. It was my room. I let out my breath and could see my exhalation as if it were a cold winter day, the terrible light catching in the cloud of my breath, and then after a few seconds even the reflected light as it hit the bedspread was too much and I had to close my eyes entirely and cover my face so that the light would not shine red through my eyelids, and I heard sounds but could not determine what their origins were, and I called out again but this time it was you I called for, Birdie— and then I woke up. My sheets were tangled around my waist, the bedspread on the hardwood floor.

I’m not embarrassed to admit that it was the first time I had spoken your name in more than ten years. I wonder, Birdie, do you ever say my name?

Perhaps you feel no glimmer of recognition, reading this description of what anyone else would think to be a dream. But as I sat there, paralyzed by light, I must have been filled with certainty and apperception. I can think of no explanation for calling out your name but that I knew that once again you could help me, and I can think of no explanation for my conviction that there was someone standing between my bed and the window, shadowless in the intensity of the light, breathing so hot that her breath didn’t condense in the boiling air, but that somehow we didn’t kill the Green Woman after all.

Please, Birdie. I kept my promise for thirty years. But I’m breaking it now.

Yours,

Patience Jane

Undated letter addressed to B. Weber c/o Weber Investigative Services, from P. J. Alexakas.

Dear Birdie,

I have written and discarded several opening paragraphs to this letter. Maybe this time I will start with an apology. Birdie, I’m sorry. Sorry I had to write to you in the first place, but even sorrier you couldn’t dissuade me from writing again.

That will have to do, though it’s not very good and I imagine you won’t like it. I don’t think there’s anything I could write that would spare me your anger. But I’m quite willing to take whatever acrimonious something you send in reply— I can only assume part of the intent of your letter was to shout me into shame, but the more I reread it the more I feel a happiness that I’m certain you will take as condescending. God, Birdie, how I’ve missed you! You haven’t changed at all, have you? This house is so quiet, and Hester has grown quieter, too, over the years. It’s been a while since I’ve had someone levy a good shout at me, through paper or otherwise.

As for the matter of my imagining this whole encounter— do you think that after a lifetime of being haunted I don’t know when a ghost is looking at me? And I don’t have your expertise, but I would say that over the past week I’ve managed to scrounge up enough additional evidence to turn a doubting mind. The scorch marks on the top half of my nightgown, the sun-bleached wallpaper of my bedroom wall, the houseplants all withered away except for the African violets, which are the same, and the potted Meyer lemon tree, which has produced six fat lemons out of season. And this morning the sugar from the cupboard was spilled on the kitchen floor in a careful star. All in all, enough to convince, I’d say, provided my audience has already passed the first hurdle of complete disbelief on their own. I suppose that type of profound rebuttal is something you have to deal with in your business, and I don’t envy you.

I’ve been oddly calm about this whole thing, as I’ve walked around the house documenting. Some of it is habit, I suppose — don’t tell me all of this is Hester, by the way, you know she was never one for precision work — but some of it is a sense of inevitability. I realize now that I never quite believed the Green Woman was gone.

I find myself doing all the regular things just the same: cooking, cleaning, and so on. All those little habits that grow like moss over the place you call home. Even sitting at my little table and carefully writing out this letter, just like how I write down my grocery lists. The scent of the hydrangeas pours in through the window, not quite as objectionable to me as it used to be when I first moved here. I’ve grown even fond of it, in a way, since my dislike is a part of my daily routine, essential and mild and even sweet, just like the scent itself. Hester, the hydrangeas, the monotony of dishwashing and laundry— you’d be curious at me, I think. I’m now a patient person in many ways. I can’t imagine but my mother would be happy to hear me living up to my name.

Even your hatred isn’t enough to stir me out of my calm path. I wrote the first letter to you: that’s done. The charm is broken, and revealed to have no protective magic after all, I think. I spent many years dreading contact with you, but in the end, all you could really do was hate me, and I suspect you’ve done so all along. Not actively, of course. I imagine you’ve packed your hate for me up in a box, the same box where you’ve packed Kathy up, somewhere in your brain. Now the box is opened and we’re both out: that’s done, too. Maybe I envy you, I can’t tell. Maybe I pity you. She has been in my thoughts for so long that my pain has faded to placidity, like the shadow of a bruise. It makes me happy to imagine us both there, me and Kathy in the box in your brain, hated and loved respectively, both to the point of pain, but together.

It’s hard to imagine you grown up. I woke up today and brushed out my graying hair and peered into my aging face in the mirror and then sat down in the scent of hydrangeas to write to a woman that I’m still picturing as a little fifteen-year-old girl. At the very oldest, twenty, looking like you did when I saw you by chance on that train platform in New York, with Christmas holly in your hair. I suppose it would be too much to ask you to enclose a current picture. Ha! God, you must be furious with me. I will admit I am stoking your hate a little. I used to do that when I was young, too, and you were even younger. Little Birdie, the spitfire, balling up her fists as if to pummel me. And Kath would laugh and laugh.

I know it’s strange and simple of me to write this letter as if you hadn’t expressly forbidden it. But know that I don’t expect our friendship to be rekindled. I don’t expect you to abandon your business, or to leave behind your daughter (“little fifteen-year-old Birdie a mother?” I think, before I can stop myself, and, “even at twenty that seems a bit much”). Heaven knows I wouldn’t ask you to brave the bus from the Lewis train station to Tamanee Rise, or the walk from Tamanee Rise to here. You may not believe me, but I’d really prefer if you didn’t come at all. Perhaps my whole calm about this thing arises from the fact that no matter how badly I deal with this, I am the only living thing in my house on its bare-headed rise. There’s no one to die from my mistakes this time but me.

One thing I do regret is that you’ve never gotten to know Hester, know her like I know her now. I wish you could know what it’s like to wake in the morning and think what will she do today? and be both scared and glad. She’s gotten so much better at communicating. Not just a word shouted in the middle of the night or a handprint in the steam on the bathroom mirror. We have whole whispered conversations at the breakfast table, and sometimes I fall asleep in my armchair reading in the evenings and when I wake up, before I open my eyes, I can hear her singing to herself. The other day I saw a bird lifting from a branch, and its springing flight shook the morning dew from the leaves, and as I watched the droplets shower down I thought— “there’s Hester”. Was that true? Sometimes at night I can feel her lying next to me, and her weight on the mattress is so definite and solid I almost turn to embrace her.

I do admit I worry about what will happen to my sweet little ghost after I’m gone. I suppose I must at least try not dying, then. Do you think you could help me in that regard?

Love,

Patience Jane

Post-script.

Woke up last night to the light again, more intense than before — both ceramic vases in my room cracked into six pieces when I returned — presence definitely a woman, saw her feet and skirt — more in my next letter — PJA

Undated letter addressed to B. Weber c/o Weber Investigative Services, from P. J. Alexakas.

Birdie,

Tuesday night. I woke up this morning and it was raining outside, a good clean summer rain. Over the course of the day a smell stayed with me, the smell of rain drying on hair, maybe? The smell of things thawing? But they had already thawed. The smell of fall? But fall wasn’t here yet. I asked Hester what the smell was, but she didn’t want to say or didn’t know or couldn’t smell it. It followed me all day, through the house, though it didn’t come from me or my clothes. It smelled like taking the train out of the city when the rain beats down against the roof and all the green blades of the rushes shake their fists at you. It smelled like Florida or laundry steam or the primordial soup of the earth. I kept thinking it would fade after the rain had stopped, but if anything it grew stronger. By the end of the day I was heaving in great gulps of it, starving for it. I hated the second between each breath.

At one point I woke up on the ground. I must have hyperventilated and passed out. The smell was kissing my face. I was sunburned on the back of my neck and arms. I still am— it is beginning to peel. I left the house and buried my head in the hydrangeas until I felt myself returning to the world.

I hope when this is all over these letters are of some use to you. Perhaps your Services girls can use it as a case study for how not to proceed. Tell me, do they wear dark suits, and do they brandish sage and sticks of rowan when encountering a spirit? Knowing nothing about your business either first or second-hand, I have been forced to extrapolate from novels and my own imagination.

In response to your questions: I have now lined the doorways and windows with salt, despite the fact that I doubt very much the effectiveness of this strategy. I refuse to burn herbs, however. Though it was not very effective in removing Hester the first time Kathy and I tried it, I have a fear that it would now be enough to expel her from me forever.

And no, Birdie. All this is not Hester. I know that you cannot comprehend living with a ghost in relative harmony, having no experience with it yourself. In understanding Hester, your childhood memories of her must be all you have to go on— the horror stories I told you when Kathy and I were both young and you were just a child. The terror I felt walking through the cold spot at the kitchen door, the strange mists that would envelop me and then pull away to leave me in a new and less real place. These things have not gone away exactly, though Hester is weaker now, and older, like me. But my feelings have changed entirely. You should know that I have lived my odd, unsettled life with no small measure of joy. I am not trapped with Hester. She is no longer even trapped with me. We struggled with each other until our struggle turned to something softer.

You say that you’re glad that a lover of ghosts is now plagued by one. But it cannot be because of my own ghost that the Green Woman has come. When the Green Woman came to you and Kathy, when she put those burns on Kathy’s cheek and your hand— Birdie, do you think that was because of anything you’d done?

Thursday morning. Your anecdote about the drifting feather in your letter gave me an idea last night, which I have begun to test with encouraging results. After supper, I tied a thread around my wrist, left the other end loose, and waited. I waited so long that I drifted off to sleep on top of my covers, still dressed. When I woke in the middle of the night, my eyes blurry and my waist and armpits complaining where my gray dress pinches me, I tried to turn over but found the thread around my wrist was tethered to something heavy and human. I closed my eyes and pulled my arm again. Hester’s hand did not touch my skin, but it came so close that the hairs on my arm, standing on end, could feel it near me.

When I woke fully and opened my eyes, the thread was loose again, though with a loop where it had wrapped around another wrist. It is an ordinary thread, and I do not think it has any power other than being convenient, and delicate. Hester has been a little standoffish, but mostly the same.

Saturday. I think it is 1 or 2 AM. All the clocks stopped last night. She wants me to come with her, Birdie. The Green Woman, she didn’t speak but she let me know. The smell, that smell of rain. It has to end soon.

Patience Jane

Undated letter addressed to B. Weber c/o Weber Investigative Services, from P. J. Alexakas.

Dear Bridget,

I have news, but I do not know how best to begin.

These are the things I know about you: you were right-handed, but write now with your left. You are a failed poet. You are a mother, with a business in debt and a dislike of automobiles. You are cruel, and angry, and give your love only to those things that you can understand. When you were twelve years old, you watched me watch your sister die.

Are these things enough for me to understand you? Do I love who you are, or only who you were? Or only who you loved, who loved you and cared for you and called you her little bird? How can I know how to tell you what has happened?

Last night I was ready, or thought I was. I woke up just as my back hit the floor of my room— my bed had disappeared, though the cover was still spread under me. Already the light and heat were both climbing. The window in front of and above me was clear again, even though last week I painted over the glass. More than clear, it was as if there was no window at all, as if there was just an empty rectangle of hissing light in the wall.

The thread around my wrist was taut, and Hester was on the end of it. Her breath did not mist in the air, because she doesn’t breathe, but she was there, I had kept her with me. She was not banished. I was not summoned alone.

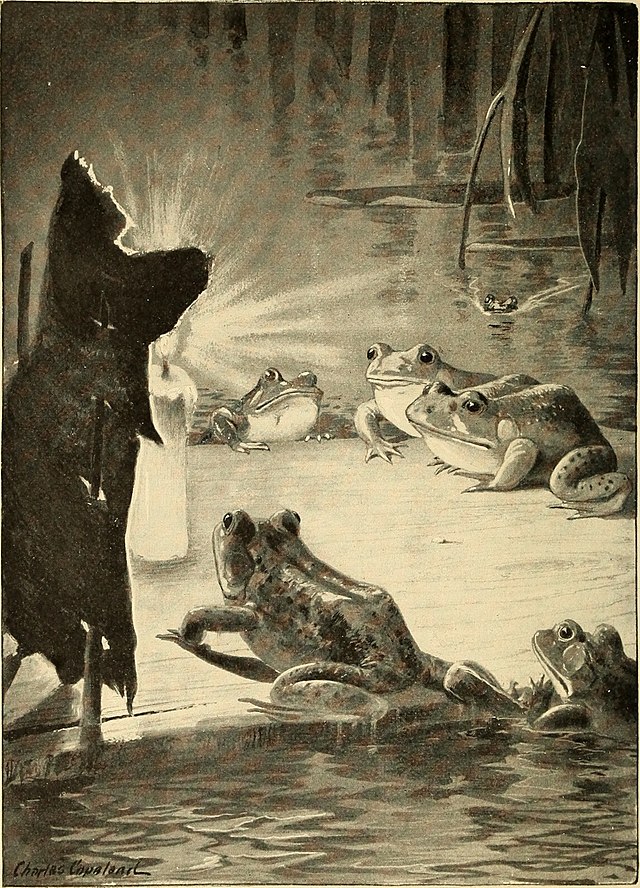

The Green Woman entered through the bright rectangle that was the window, crumpling and tearing the paper wall with her feet as she stepped through. She was a wavering dark shape against the light, and I tilted my head back and looked up at the ceiling. The sun was shining so bright outside that sunlight was squeezing between the roof tiles and condensing on the boards of the ceiling in fat golden drops, which fell down and struck my cheeks like tears.

I still had the two pieces of iron in my pocket, and I retrieved one and tried to throw it at the Green Woman. My arm was so weak in my dizziness that I dropped it on the floor.

As the light grew brighter, Hester grew more and more visible, first just a blur, then sharpening, a pristine shadow against my bedcover. In the unrealness of this room, I felt her put her hand solidly in mine. I turned toward her and kept my eyes open so I could keep watching her, wanting to see more.

I’ll admit I thought you might burst in again, just like last time. Maybe even with a weapon, brandishing the old sword, or some kind of ghost-killing gun. Surely you must be a good shot, even with your left hand. But you wouldn’t be able to truly kill her this time, any more than you did last time. Another thirty years and I might be dead, but what if you aren’t? I can’t bear the thought of you facing her alone.

The Green Woman leaned down close over me. I really felt for the first time the terrible damp humidity of her heat, her breath hissing over my face like steam and turning my skin boiled-red. The plain green of her dowdy dress was close to me. It was an everyday factory linen, but occasionally it was something else. She leaned in even closer. The green of her dress was visibly alive, made up of hundreds of tiny glossy leaves and the shining iridescence of an insect’s wings. I finally dared to look up at her face, which had a palm leaf folded modestly over it. All of this thought and observation passed through my mind in an instant as she leaned over me. I could not stop thinking and guessing even as I believed that I was about to die. But I did not die.

A hand entered the Green Woman’s chest. It was not a normal hand, because I could not see it outside of her chest, but as it entered her chest it became entirely visible, a precisely-edged shadow which I could see as well as if the Green Woman were transparent. She made no sound, but she shuddered as the hand entered her. She tried to back away but the hand had wrapped around some ghostly organ inside her and held her fast. The palm leaf in front of her face quivered.

Hester moved the hand upwards, up through her throat into her head. The Green Woman jerked her head around but could not escape. Again, she made no sounds, and I wondered if she could make sound.

I reached up and pulled the leaf away, and stared into Kathy’s panicked face.

Bridget, I don’t pretend to know how these things work. Not ghosts, and not people. I don’t know what died in that hotel room thirty years ago, or what faced me in my bedroom last night.

I wonder sometimes if the Green Woman frightened her too— Hester, I mean. You keep talking about the four of us in that terrible final confrontation, you, Kathy, me, and the Green Woman. But Hester was there too. Paralyzed, like us. Afraid? It’s hard to know.

But I like to think she feels things, the same as we do. I think she hated the Green Woman. And I think she loves me. What she thought of Kathy, I’m not sure. And you, Bridget, who she only met the once, would she love you or hate you? Would you love her or hate her if I tell you what she’s done?

I wrote to you first for your help, but also for the simple pleasure of awaiting your reply. I have been lucky for these two letters from you that sit here on my little desk, and will likely revisit them often. After the silence following my previous, I do not expect any more. I write this last not to give you pain, or to taunt you, but in the hope that, now that you have opened up the box of your heart’s love and hatred, and observed what is within, you can know them now for their true forms. Tough, tender, variegated.

I must go now. It’s time for our dinner.

Love,

Patience Jane

Note from Ann Weber Li, executor for the estate of Bridget Ann Weber

To the Acquisitions Board:

I’m in a difficult position, because my mother always drilled two things into our heads, above all others. First, that her work was the most important thing she’d ever do, and second, that you shouldn’t talk about your personal family business to strangers (or to family, for that matter). But if you’ve read these letters, you know that this bit of personal family business has to be talked about if we’re keeping the proper record of what she’d call a “unique supernatural phenomenon”. So I’m sending these on with the rest of her papers. I don’t mind you knowing our business, myself. Over the years I’ve cultivated a habit of emotional honesty, likely as a reaction to my mother’s parenting style, actually. You can imagine my dismay when it manifests itself as a brusqueness that sounds just like Dr. Weber herself. Oh well, too late to change now!

So let’s see what I can put on the record that might make this story more complete. I got these four letters from the hospice worker after my mother’s death, along with the rest of her things, and I was very interested to read them, since as I’ve said, my mother didn’t talk much about her “emotions” or “childhood”. The first time we even learned she had a sister named Katherine was when our rarely-seen grandfather was visiting and mentioned it off-hand. She wasn’t in the room, of course, since whenever family visited the house she always made herself busy with chores or urgent issues at the office. Only once the friendly intruder had left would she suddenly have time for meals and conversation again (mostly stuff she thought was good for our “academic development”). If we asked any impertinent questions or brought up dead siblings, after all, she could silence us with a single, well-practiced look.

All this of course is why it’s so weird that I even had any idea about the Green Woman as a kid, though I can promise I did. I suppose there’s an outside chance she might have said something as we went past the old hotel, now derelict. Or maybe she used some part of it in a lesson plan and I overheard it while hanging out in the back of the old classroom. I did definitely read through all her diaries, though to my disappointment they only had birthdays and appointments in them.

But I think the most likely thing is either that I just picked up on it, psychically or whatever (unfortunately I never listened very closely when my mother discussed supernatural heredity of memory), or that, just maybe, she did say something about it once when talking about her hand. When I was a kid I would hold her messed-up burned-up hand in mine and run my fingers along the roads of her pink puckered skin. That hand both scared and fascinated me.

But anyway, however I learned, when I was about eight I knew enough to have bad dreams featuring the Green Woman almost every night. And here’s the real purpose of this letter. I don’t have my mother’s responses to Patience Jane to give you, but I do have the story from my childhood nightmares.

They always started with me walking along the edge of that street in Midtown. I can still picture the fancy doors and the long front of the building ahead of me. The lights are all lit up, it’s dark outside. Then I’m in the hotel, going up the red stairs to the room. And here’s a grain of salt, the inside of the building always looked a lot like the Omni Parker House Hotel we’d stayed at once in Boston when I was a kid. This may be a hint that a lot of the dream was just made up by my brain. On the other hand, hotels honestly all look a bit the same.

I’d get to the room door. Sometimes it would be open, and sometimes I’d open it myself, and there was that strange and horrible image that always stood out most vividly. The three of them in the room, totally still in the hot air, like a painting.

Everything is going so slow that I can see the heat rolling off of her, waves on the shore. The Green Woman is hanging in the air. I remember the embroidered bedspreads. Two girls are there and I don’t recognize them, but I see one of them is falling backwards away from the Green Woman with a sword in her hand, and she has two shadows. The other girl’s leg is stopped mid-kick against a green dress, and her hands are frozen mid-clutch at the green hand that lifts her by the throat. I am very scared by her face, molasses-slow in a mask of agony.

So you can see the main problem here, that the surrealism of a dream can be very close to the surrealism of a powerful ghost, right? Could that scene have been real? Maybe it really did look like a painting when it actually happened, and maybe it did feel like a dream.

Remember, I’m still in the door at this point. Sometimes now I look down at my black shoes and white stockings. My mother always bought the same type of practical shoes for us, and it’s easy to imagine that her mother made her wear them too. They could be my childhood shoes or hers.

“Oh look, it’s Bridget.” This is what the Green Woman says when she sees me, so casually that the room around her suddenly seems comedic. Her voice is very normal. The molecules of the air in the room move so slowly that I can hear them sigh like an accordion breathing in. Then she lets go of the strangled girl’s throat, and there are ridges in that throat where her fingers were. Even the skin can’t spring back. The Green Woman steps down from where she’d been floating and walks over to me, grabs me by my right hand and pulls me into the hot sauna of the room

“Don’t look, child,” is what she says next, and she moves me so that I can only see the other girl where she’s falling, each of her shadows as still as pools of ink on the carpet. I can only assume that at this point the Green Woman climbs back up into the air and fits her fingers back into the grooves in my Aunt Katherine’s neck, but I’m not looking in that direction, and at any rate, that’s where the dream would end, with me waking screaming in my bed and shaking out my right hand like it was on fire, and someone clumsily comforting me and shushing me and wiping my sweaty hair off my face. If we’re including everything, I’d often wet the bed too.

So, what was that all about?

Obviously there’s a lot there that I can’t have known about on my own. But there are also some things that don’t match with what Patience Jane says in her letters. I don’t have a head for this kind of analysis myself, so hopefully I’ve written down the dream well enough that someone can look at all these things together and know what it all means.

The nightmares stopped eventually, of course. I’d almost forgotten about them by the time I was fifteen, when one day my mother got up in the morning and made breakfast and got the mail as usual and then just went kind of crazy. She stayed home from work and spent the morning papering over the windows, and then sat and talked with us in the living room all afternoon, and even slept in our room that night. By that time I was (all teenagers think this!) quite grown up at fifteen, and resented the intrusion. But even my self-absorption was punctured by the fact that my mother seemed actually afraid. It’s an understatement to say that fear is not like her.

I remember asking her, as I turned down the bed and she settled into the chair where she’d spend the night, what she was frightened of. And she said, just like that, “the Green Woman”. It must have been five years since I’d had one of the nightmares, and I’d almost forgotten them, but as soon as she said that, I thought “oh, the ghost I used to dream about”. Of course, what bothers me now is that this must have been the first time I’d actually heard that name spoken, but I certainly knew exactly who she meant, and I think that’s how I’d always thought of her. It could, of course, just be because it’s an obvious name.

By the next morning she’d changed her mind. She tore down the paper from the windows again. We had a few more bad scenes over the next few weeks, which must have been the next three letters, but nothing that drastic again. And then nothing about it came up again for more than thirty years.

If I’d read these letters before my mother died, I think that I would have had a lot of questions for her, and maybe they’d even be good questions that meant something. But then, if she were alive, she’d probably just give me that steely look, and hold her hand out for the return of her four letters from Patience Jane.

I’ll have to comfort myself with the fact that this letter, though it’s written by a purposeful amateur who only ever met one of the people concerned, might be some useful data in that great Project that was my mother’s favorite child. And also with the fact that I let my own daughter wear pink sparkly tennis shoes.

Best,

Ann Weber Li