Pariang County, Unity State, South Sudan, December 2014

Dear Jérôme,

It’s the day after Christmas. I am in a pick-up truck in the north of Unity state, driving from Pariang town towards government-controlled oil fields close to the Sudanese border. Six months ago, you were in Leer, and I think that if there were a good road, it would only take a few hours to drive south and see if your friend Ruth had returned home. It’s a brief thought. Though from Pariang to the oil fields is but a tenth of the distance to Leer, it’s already midday, and we have been on the road for five hours, bumping up and down in the dusty heat of the dry season. Between Ruth and I there are hundreds of miles of unpaved tracks, with checkpoints arrayed along them.

Through the window of the pick-up, I peer out at an empty landscape. A flat plane of red clay extends to a horizon set on fire by farmers clearing the bush. On the Sudanese border, the panorama changes with the seasons. In July, after a few months of rain, this whole area will be a vibrant green, almost neon under the harsh sun. Now, the landscape around me has been stripped by heat and war, rendering it almost entirely devoid of life.

Occasionally, we pass the burnt-out remnants of tukuls—the clay and wattle huts, thatched with elephant-grass, which are the primary form of abode for the Panaru Dinka of northern Unity. Only the outlines of the tukuls remain, indicated on the ground by the rubble of the walls, like plans for future houses sketched in fragments of clay. With the next rains, the last traces of these dwellings will be absorbed back into the earth. These ruins we pass over in silence.

The sole buildings still standing are army barracks, government offices, and schools. All these outposts of the South Sudanese state look curiously similar: squat, one-story brick and concrete constructions, scarred by the conflict. It is as if they are part of a stage set for a long-abandoned film, its production hopelessly over-budget. Each building provides a prompt for Guor, my travelling companion, to tell me a story. He sticks to his script. Here is where we fought the rebels after the South Sudanese army, the SPLA, split in December 2013. Here is where we fought them as they moved south towards Bentiu, the state capital. At the end of each story he says, “we won,” and smiles shyly.

Guor is a young man, perhaps seventeen years old. He finished primary school at a refugee camp in Uganda and returned to Pariang, where he is now the secretary for the county commissioner. His principal task is to write the letters that the commissioner sends with abandon. Mostly, Guor tells me, they are addressed to Juba, the national capital, and mostly, he says, they ask about money. The commissioner told Guor to assist me as I travel through Pariang and to ensure, I suspect, that I don’t ask the wrong questions, or see anything untoward.

On the way out of town this morning, a pick-up truck full of men wearing turbans roared past us. The letters ‘SLA’ were painted on the side of the vehicle, indicating that the truck may have once been the property of one of the factions of the Sudan Liberation Army, one of the Darfuri rebel groups that the government of South Sudan insists have no presence within the country.

“What,” I asked Guor, “was that, if not the SLA?”

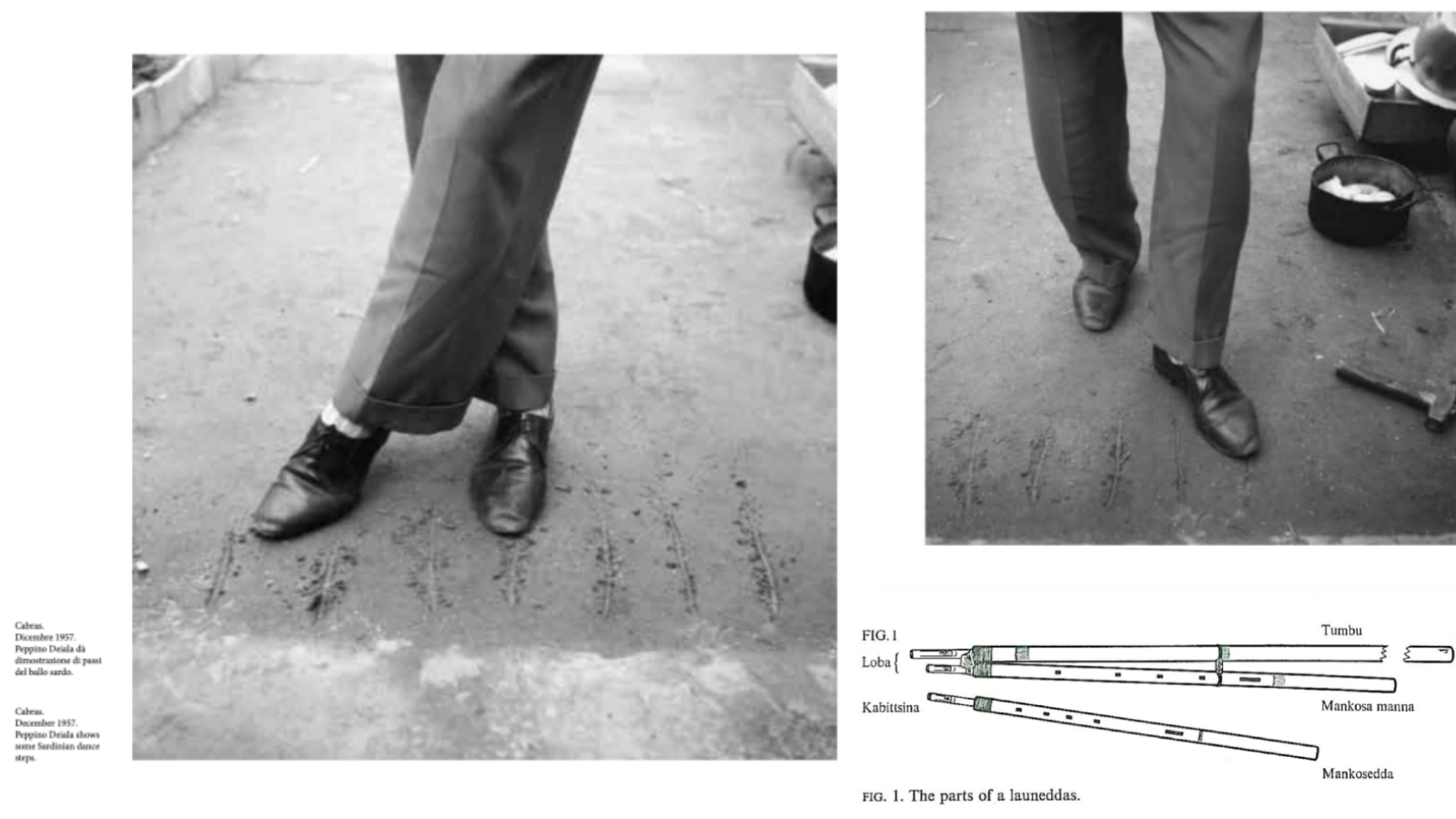

“You see, Joshua, the people of this country are very poor. They have no education. Like commissioner. The soldiers meant to write SPLA on the truck, but they had no schooling, and spelled it badly.”

Guor smiled and looked at me sheepishly, before explaining our conversation to the SPLA soldiers travelling with us, who collapsed into laughter. For the rest of the day, one of them repeatedly asks me, “where is the SLA?” and then wanders off, chuckling to himself.

*

As the miles unfold, I see neither more SLA vehicles, nor much of anything else. The flat red earth is unrelenting, and Guor’s triumphal victory narrative begins to feel staid. I go over the course of the war in my mind and struggle to remember who fought whom, when, and why. A year earlier, in December 2013, when the conflict began, I would have given anything to be here. I was in Luanda, Angola, speaking to SPLA officers over bad satellite phone connections, hurriedly taking down the details of battles, vainly trying to verify them, and writing up report after report: strings of names and dates commended for their level of detail by experts in the field, while I talked to my girlfriend about the conflict, and she struggled to remember who had fought whom, when, and why. Everything felt so concrete to me then, sitting on the other side of the continent. A year later, on the ruins of the battlefield, I suddenly feel like I don’t understand anything at all.

The pick-up comes to an abrupt halt, dragging me from my thoughts. Around twenty cows block our path, ambling along the road ahead. Access to good grazing has been difficult during this war, and the cows are emaciated. Proud longhorns sit atop the raw outlines of ribs, supported by skeletal legs, as if sketched by a child. Our driver revs the engine and the pick-up snarls at the cows, but they pay it no mind. Our journey slows, all urgency forgotten, and we drive behind them, the truck rumbling along at the pace of their ruminations. Finally, after five long minutes, two boys come running out from the bush and with small sticks, like teachers in front of a blackboard, they guide their recalcitrant pupils off the road.

As we drive slowly past the cows, Guor whispers their names over the throb of the engine, softly enough that each sounds like a seductive promise. “Mior ma nyääl,” he says, pointing at a white bullock splashed with brown spots. “Mior ma nyang,” Guor says of a bullock brindled in brown, “like a crocodile!”

For the Panaru Dinka, reality is—to a certain extent—a cow. The brown blotches on Mior ma nyääl’s skin are said to resemble the pigmentation of the ball python from which the bullock derives its name, while nyang literally means crocodile. One could say that cows derive their names from creatures in the world, but the reverse would be just as accurate: cows provide the patterns according to which the world is comprehensible. Colors, like animal names, are often derived from the markings of cattle. As a child, Guor saw Mior ma nyääl and recognized a color pattern; he still hasn’t seen a ball python.

As the pick-up clears the cows, Guor starts quietly humming a song. As a young boy, he and his age-mates would walk for weeks with the cattle in search of pasture, singing as they went. This part of his life remains unknown to me. He refuses to explain the song he is singing and flashes the same shy grin he displayed when recounting the SPLA’s recent military victories.

Cattle still determine many of the rhythms of the lives of the Panaru Dinka, but their world is changing. It used to be the case that young men received both an ox and the name of an ox (a young man’s ‘cow’ name) upon initiation, after which they could begin to acquire cattle of their own and think about marriage. Guor tells me there hasn’t been an initiation since 2005. That was the year the second civil war ended, fought largely between the SPLA and the Sudanese government in Khartoum. It should have been the year that everything else began. In 2011, South Sudan would secede from Sudan, and become, as the cliché goes, the world’s newest nation. Increasingly, however, 2005 seems to mark the end of many things. Guor doesn’t dream of cattle and initiation, but of further schooling in Uganda, and then a job with one of the NGOs that minister to South Sudan’s perpetual war.

We manage to drive for another twenty minutes before two more young boys emerge from the bush at the side of the road, a hundred meters in front of us. Rather than cattle herders, these young men are soldiers, and carry AK-47s instead of sticks. They wave us over in a manner which indicates that, despite their tender age, they are accustomed to being obeyed. We stop and the boys approach the driver, holding the barrels of their weapons level with the cabin of the pick-up. I am relatively unconcerned. The government has a firm grip on the oil fields, and the commander of the SPLA’s 4th Division in the area, Nelson Chol, has already informed the soldiers guarding the fields that we are on our way.

The two young men beckon us up a small dirt road towards a copse of trees. There, behind an elephant-grass wall, is a tukul. In front of it are some plastic chairs, and the commander of this group, Achuil. On a table in front of him are keys, tea, and a satellite phone: the must-have items for any self-respecting military leader in South Sudan. He has been expecting us, he says. We exchange pleasantries and I explain who I am and what I am doing, while Guor translates into Dinka. Achuil seems affable enough, but when I ask about rebel positions to the north of the oil fields, he hesitates. He has a problem, he explains, and gestures at the Thuraya satellite phone. Chol’s call about our visit was the first contact with his superiors that he has had this week, and he cannot use his phone, for he has no money. In my pocket, I detach a thin strip of Thuraya credit from my supply and pass it silently to the commander, who begins talking more expansively.

The rebels, he says, are not to be feared. They have forces on the Sudanese border at Panakuach, an hour away, but they are too weak to take the oil fields. The real problem is the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS). Last week, a UN patrol moved south into rebel-controlled areas after visiting Achuil. “They just drove straight through,” he says. “We won’t let them pass again. Whose side are they on?” For the UN, such actions don’t seem problematic. “We are impartial,” a UN officer will tell me later on the same trip, “we don’t take sides.”

For these beleaguered soldiers, impartiality is not an option. When the civil war broke out, everyone was forced to choose: At the oil fields, employees who belong to South Sudan’s two largest ethnic groups, the Dinka and the Nuer, engaged in tit-for-tat killings. SPLA units disaggregated and fought against each other, while the Nuer population of Pariang fled south to rebel-held areas. This is war. Everyone must choose, and everything helps one side or another. A UN patrol that sees atrocities committed by the rebels and not by the government can be a useful part of the war effort, and thus the government prevents UN access to areas it is attacking. An aid operation set up in rebel territory will mean that some food or medicine will get to the rebels, and the reverse applies; humanitarian agencies are desirable real estate.

During the first year of the war, Bentiu changed hands multiple times. By December 2014, the state capital was almost empty, inhabited only by government troops and their families, squatting in the ruins of the city. Bentiu’s former residents peered out at their homes from inside the Protection of Civilians (PoC) site in the UNMISS base, while the state-government muttered darkly about the “rebels” benefitting from UN assistance. Aid agencies had set up shop in the PoC, but the governor claimed this was unfair and two weeks before I arrived in Unity, had insisted that a food distribution should take place in Bentiu itself. “It was a sham,” a humanitarian who witnessed the event told me. “The SPLA had assembled their families in the middle of town, and stood around, telling their wives and children what to say as they were interviewed by aid workers.” To the aid agencies’ credit, many of them refused to participate in an exercise so clearly controlled by the army. Some agencies, though, wanted to ensure they appeared impartial—while also currying favor with the governor—and organized a limited aid distribution. It is undoubtedly true that the soldiers were also hungry.

What I most urgently want to convey to people who have never been to South Sudan is that there are no neutral positions in this war, and no actions that don’t have political consequences. The soldiers with whom I sit this afternoon see the situation lucidly enough. Everything is recruited, resources as much as people. Talking to these soldiers, the UN’s stance of impartiality seems as impossible to me as it appears inexplicable to them. Where do you stand, they want to know: with us, or with the rebels?

When we last met, you asked me if I have ever hated South Sudan. I don’t hate these young men, guarding an oil field that has never benefited them, while living off pumpkin leaves and hoping for wages. There is honesty in their world; they know that everything and everyone must take a position. What enrages me is the willful blindness of the UN and the NGOs. Is aid being diverted to an army that is carrying out massacres? The international community shrugs its shoulders and pretends to exist in a purer moral air, which hangs above the battlefield. It doesn’t acknowledge that everything takes a position. The oxygen of morality hides more tawdry bureaucratic injunctions. There is food to be distributed. Boxes to be ticked. Reports written on the amount of aid disbursed. Statistics to be used in funding drives. South Sudan’s crisis will appear—if only for a moment—on North American television screens. Donations will follow. In living rooms across the US, we will hear people asking: “How can we stop the horror?” (As if we were not already part of the horror). The fervent need to help is what I hate—this urge to help, to do something, anything, that comes before, and takes precedence over, precisely the people that the help is supposed to help.

My hatred of the NGOs and the UN is also a question of permissibility. I feel righteous anger because we are kin: foreigners to South Sudan. We all ask what we are doing here, and struggle to exist in a world that is not our own. In contrast, any critique I have of the forces slaughtering each other in Unity state is abstract. I feel I must understand before I criticize, and think I understand the NGO workers all too well. This is the incoherence of my moral compass. I sit with commanders responsible for massacres, and we drink, and exchange jokes all evening, and then when I interact with earnest young NGO workers, fresh off the plane from Nairobi, the best I can sometimes muster is a contemptuous snarl. I become friends with those furthest from me and hate those closest.

On the long flight from Chicago, via D.C. and Addis Ababa, to Nairobi, I re-read the book that you wrote, Chroniques du Darfour, composed of letters to your father. He lived in Darfur in another era, when the lines delineating the distances between people were drawn differently. You wrote:

You liked fieldwork. You felt like a fish in water, as you liked to say. Sometimes, I ask myself what I am doing here, plunging for a few weeks into the everyday life of a country at war, knowing perfectly well I have my return ticket. I do not believe you had these doubts. Because you were born in colonial Algeria, you did not see yourself as a westerner observing foreign bodies. Studying on a scholarship at the colonizer’s school made you erudite, but you remained an “indigene” as they said back then, and you were an early partisan of every independence struggle. In Sudan, you felt you were among your own people.

For your father, a collective way of life was imaginable, in which one could work together with the people of Darfur and share a vision of the future. We arrived in Sudan at a different moment, too late for anti-colonial partisanship. I have long been suspicious of an older generation of Sudan experts who, having missed the anti-colonial wars, found a late variant in the SPLA’s struggle against Khartoum. They remained romantics after the independence of South Sudan, clinging to a heroic image of the war, forgiving the government its sins, even as the country fell apart.

The experts’ identification with the SPLA is another variant of the NGO workers’ paternalistic vision of South Sudan. While the latter deign to help the victims of the conflict and presume to know their desires and problems, the experts romantically chose a side, lending a hand to a struggle not their own.

Am I with the SPLA or with the rebels? I cannot answer the soldiers’ implicit question. There is no collective subject imaginable between me and these young men, and no shared vision of the future. I will never be South Sudanese, and world history is not at a point at which we could link arms and call each other comrades. The soldiers understand my place. I might think of myself as a researcher, but for them I belong to the world of NGO workers and UN staff: the people of no place, with high salaries and return tickets. The people who have no clear answer to that nagging question: Why am I here? It is a thin solidarity that we share, forged not by common cause, but by air miles.

At the oil fields, no one asked me why I was in the north of Unity state, though I had prepared my uneasy reply. Mabek Lang, the deputy governor, had invited me to spend Christmas in Pariang.

*

I arrived in South Sudan a week ago to do field research for a report for a Swiss organization on the conflict in Unity state. I was last in Juba, the nation’s capital, in 2012, before the conflict began, and walking around old haunts accentuated the differences. Everywhere I went, eyes narrowed. I met a Nuer contact at the Grand, an old hotel that I thought would be empty in the afternoon. We sat outside amid broken parasols, drinking bad coffee in the stillness of the dry-season sun. Half an hour after we arrived, three Dinka men strolled past, turned around, and immediately started to walk up and down next to us, staring with unconcealed malice, our conversation withering under their gaze.

I started meeting contacts in my hotel room and playing John Coltrane’s Transition as loud as my laptop would let me, the frenetic saxophone drowning out—or so I hoped—our whispered discussions about the SPLA’s assault on southern Unity. For the government, everyone was a potential rebel, and in bars and hotels, I policed my conversations, doing the work of the national security services to stave off their appearance. Strange to think now that the tumultuous period between 2005-13, for all its difficulties, turned out to be a high point for southern Sudan, and for the possibilities of doing research here.

All of Juba was on edge. The black-market exchange rate between the dollar and the South Sudanese pound jumped with each new clash in Unity. My Kenyan friends, drawn to South Sudan by the influx of oil and aid money after the signing of the peace agreement in 2005, talked for the first time about returning home. It felt like the end of an era. After a couple of days in Juba, I too was ready to leave, but for Bentiu, rather than Nairobi.

That is not as easy as it might seem. The enterprising firms that provided private sector aerial transportation in southern Sudan from 2005-13 closed their doors shortly after the conflict began. To travel overland from Juba to Bentiu would have taken at least a week, if I could have somehow managed to get past all the government checkpoints. At this point, there are only four functional transportation infrastructures in the country: that of the oil companies, effectively off-limits to researchers; that of the UN; that of the NGO community—itself largely parasitic on the UN agency that organizes flights for humanitarians, UNHAS—and that of the SPLA. To move around South Sudan at war requires ingratiating oneself with one of these communities. This is one of the reasons that journalists and researchers are so reluctant to criticize the UN and NGOs. If you are blacklisted, you lose your means of travelling around the country and access to the officials whose quotes pad out every story on South Sudan. As a Marxist, I never realized how much I would miss free market capitalism until I tried to organize flights out of Juba.

On previous trips, I had flown with the SPLA and a variety of NGOs. On my second afternoon in the capital, I had a meeting with an organization with which I had previously travelled around South Sudan, and that had suggested it could assist me in getting up to Unity. Over instant coffee, I met the NGOs’ country team. The director, an affable British woman who had recently arrived in Juba, asked me for my understanding of the situation in Unity state. I launched into an impromptu presentation. The director was seemingly impressed with the whirlwind of information that I summoned up, though by the end of my talk, she seemed somewhat surprised, and there was a guarded pause before she responded, “Well, that is all very interesting.”

I asked the director what she knew about the situation in southern Unity, where her NGO had operated before it shut down due to the conflict, and she deferred to her security officer. He explained at great length that the area was largely peaceful and pro-government, with some regrettable bandit activity. This was not what I had heard from my sources and it ran contrary to every report on what was going on. It was, in other words, a lie. The director smiled, and said of her security officer, who was a young man almost certainly in the pay of the security services: “He is so knowledgeable.” “Might your organization,” I asked, shifting the conversation to the director, “be able to facilitate my travel to Unity, as we discussed?”

The director smiled. “Everything is rather tense at the moment,” she said. “Rather tense. If we were to fly you out to Unity, and you then made allegations about government activity, that might endanger our operations in the country. However, if you were to restrict yourself to reporting on the humanitarian crisis, and the urgent need for more assistance, well, in that case,” she smiled, “I am sure we could be of help.”

All across Juba, even old friends told me the same story. Your work is too dangerous. We can’t take the risk. Things have changed. A week before I arrived, a group of South Sudanese aid workers had been arrested at an airstrip in Unity, on suspicion of being rebels. Journalists were being detained. The internationals were deported, while the South Sudanese disappeared into SPLA military prisons. Things, as the director said, were tense.

*

The day after my meeting with the NGO, I went to see M, an old Jikany Nuer friend from Bentiu, who now worked for an American organization. We met at his office; foreigners came and went all the time, and my visit wouldn’t arouse any suspicion. Under the strip lighting of the container, I saw M’s eyes: tired, almost hollow. Since December 2013, when government forces went door-to-door killing Nuer civilians in Juba, he had been living in fear. He sent his family to Uganda, like so many South Sudanese, and remained only because his job provided a thin stream of income for his children’s schooling. We didn’t talk about what happened the previous December. His life had shortened. “I move,” he said, “between my work and my home, and the walk between the two compounds is terrifying. I don’t go anywhere else. Any Dinka can kill me now, and nothing will be done,” he said, referring to the dominant ethnic group in the government. There was a long pause, and we stared at each other, before he asked, “And what, Joshua, can I do for you?”

*

The Unity state coordination office, where the state-level government does its business while in Juba, was a recently requisitioned building, and the long line of rusting black tuk-tuks in front of its yellow walls stood testament to another, more profitable moment in Juba’s recent history. M entered the building twenty minutes before me. The organization he was working for was assisting the government with the migration of Sudanese nomads and pastoralists, groups that annually cross into South Sudan in search of dry season grazing. He had some things to discuss with the commissioner of Pariang county and might be able to introduce me, if I were to show up.

As I wandered into the building, I was confronted by a stern sign: ‘All employees must go to Bentiu to receive their salaries.’ The government wants its workers in the state capital, while they would rather collect their pay in Juba’s more commodious confines. It is not, after all, as if there is much to do in Bentiu: the city is a ruin, social services non-existent or else provided by NGOs, and half the state under the control of the rebels. Though there is little for the state’s employees to do, it is important that they are paid. Wages are considered an obligation of the state—a way of distributing power and keeping people in line—rather than payment for work done. This isn’t corruption or laziness, but the reality of a country that war has dragged to a stop.

Over the following week, I spent a lot of time at the coordination office. The county commissioners and ministers competed for the few available desks. I am sure you have been in offices like this before. There were no computers, only occasionally electricity, and no papers to be seen. The governor of the state, Joseph Wejang Monytuil, never came in. Some employees claimed he was there very early in the morning, before I arrived, but this wasn’t credible. Juba’s real politics takes place in hotels, where powerful old men hold court and make decisions during meetings whose existence is not marked on any office calendar. The state-level administration, in contrast, is populated by young men sitting on aged couches. I spent hours there, waiting for ministers who often failed to show up. The young men slouched around me were waiting for a meeting, a job, some money—an opportunity to make something of their lives. Mostly, though, they were just waiting. Their passivity is structural. In Juba, power and money flow downward, and without the intercession of a higher being there is little to do but wait.

That first morning in the office, I asked one of the young men draped across the couches in the entrance hall where I might find Monyluang Manyiel, the Pariang county commissioner. Guor stopped playing with his phone, and walked me into a dark room, with cheap faux-wood paneling. M was already there, a satellite phone in his hand. He introduced me to Monyluang, a small man in a cobalt safari suit, and then made his excuses—he had to go and arrange the migration into Pariang that was to occur the next week.

Monyluang and I talked about the migration, life in Pariang since I last visited in 2012, and how proud the Panaru Dinka were of their favorite son, Mabek Lang, once the county commissioner and now the deputy governor of the state. It is Mabek who was behind the commissioner’s appointment, but of this, I say nothing. In a country made suspicious by war, and tired of the foreigners who move in and out of South Sudan, I have learned that to get someone to trust you takes a long time, and immediately asking direct questions rarely gets you very far. At the end of our chat, I hazarded simply to ask whether Monyluang would be returning to Pariang anytime soon. Why yes, he replied, smiling, we must return with everybody’s salaries, in time for Christmas.

*

My other options exhausted, I had to get on that plane to Pariang. So began my wooing of Mabek and Monyluang. The county commissioner had taken up residence at The Africa Hotel, on a rough, unpaved road behind the university. After our first encounter, we had decided to meet at 10 am the next day, at the hotel. When I arrived, Monyluang had already left, and calls to his phone were left unanswered. Finally, after hours spent drinking cups of strong Ethiopian coffee, I got through. We made another appointment. Monyluang again did not show up, and the process began anew. Some mornings, I simply went to his hotel and waited.

At Logali House, where I was staying, my days spent pursuing Monyluang were met with knowing smiles from NGO workers and journalists. The South Sudanese, they said, have no sense of time. I disagreed. Monyluang has a very acute sense of time; it was simply that he did not have time for me. South Sudan has neither had a long history of generalized wage labor, nor endured the long decades of the 19th century that it took Britain to work to a clock. Meetings start when the right people arrive, and the right people only arrive when the meeting starts. Time clusters around relations. Monyluang’s sense of time revolves around himself and his place in the political hierarchy of Unity state. I come somewhere close to the bottom of the list. Why should he have made time for me?

I took this state of affairs as something of a personal challenge. Through Guor, I had already suggested I might join them when they returned to Pariang, and he had no doubt passed this information to Monyluang. After three days, I finally managed to meet the commissioner outside his hotel, as he was getting into his car. Pariang? “Yes,” he said, “we will see. Have you spoken to Mabek?”

Mabek Lang was staying at the Concord, a rather better hotel than The Africa, as befits the deputy governor of the state. Early the next morning, I walked past a tired buffet of ageing ham and eggs and into the dark main bar of the hotel. I hadn’t seen Mabek since 2012. During the second civil war, he was the military commander of Pariang, and with the signing of the peace agreement, he had become the county commissioner, though his hold on the territory was no less absolute. He was sitting in a corner booth, and I was about to walk over and introduce myself when he raised his hand, indicating that I should stop. I took a seat at the bar, and slowly realized that the room was an antechamber. Everyone was waiting to meet Mabek. I ordered a coffee and took my place at the end of the queue.

Our meeting, when it finally occurred, was over quickly. Not knowing whether I would get another chance to talk to Mabek, I asked him direct questions. What part did you play in Taban Deng’s termination as governor in 2013, when South Sudanese president Salva Kiir removed him from office after Taban Deng decided to ally with Riek Machar, the Nuer vice-president? Why did Monytuil, the current governor of Unity state, side with Kiir over Machar when the civil war broke out? His answers were pat, formal. I could have written them out in advance. Finally, indicating that my audience was at a close, he said, “And I do hope you will join us in Pariang for Christmas.”

*

The biplane taking us to Pariang shook so much that conversation proved impossible, and we all vibrated together, withdrawing into our own thoughts. Back in Juba, Monyluang had promised me a car, a full tank of petrol, and an armed guard, with free remit to go wherever I wanted. For a researcher in South Sudan, this is akin to being promised a unicorn, and as we flew north, I couldn’t quell the doubts gathering in my mind. At the airport, I had met two journalists who were to accompany us north. Mabek had apparently decided that Pariang had some good news to share with the country, and both journalists seemed happy to come along. South Sudanese writers don’t have an easy time; there is no money to get around the country and heavy censorship. An invitation from the government can’t be turned down. I didn’t dislike either of them, but their presence made me anxious, and filled my head with visions of the three of us dutifully attending the Pariang beauty pageant, my hopes of research reduced to a series of public relations exercises devised by Monyluang.

From the landing strip at Yida, South Sudan’s largest refugee camp, a welcoming committee whisked us away to an arrival celebration. Outside a large tukul, a thin chalk line had been etched into the clay, its border zealously guarded by SPLA soldiers. Children amused themselves by skipping around the edge, while the soldiers chased them away, weapons raised in mock seriousness. Inside, we sat on plastic chairs in sweltering heat, listening to the first of many speeches praising Mabek’s leadership and the wonderful gift of this Christmas visit to Pariang. After an hour, I excused myself, and went to wander around the market; it was there that I understood the meaning of the speeches.

“Life is hard,” Abdulrahman said, his keen eyes assessing me as if I were a prospective bulk purchase for his stall. He was from Darfur, one of many traders who use a network which now stretches across both sides of an international frontier, and for whom the creation of a new nation was a business opportunity. He moved to Yida shortly after South Sudan seceded, when the camp was created. “Business is bad,” he complained. Before independence, this part of southern Sudan was always more economically connected to Khartoum than to Equatorial Juba, a thousand miles to the south. Goods used to come from Heglig and Kharasana, just across the border in South Kordofan. After 2011, and South Sudanese independence, the Sudanese government closed the border as a means to put pressure on the South Sudanese government, and now many goods have to come by plane from Juba. Prices have skyrocketed, and some traders, connected to Sudan, have found alternate means of getting stock. “Everything I have here,” Abdulrahman told me, gesturing at the neatly pressed clothes hanging all around him, “comes on motorcycle, smuggled across the border.” Despite the availability of goods, the market seemed subdued, and as we sat drinking tea, Abdulrahman told me that no one was buying. Though Yida is a refugee camp, it is also a garrison town, reliant on the salaries of the officials and the SPLA soldiers stationed there for injections of fresh currency. No one had been paid in months.

Still, he said, things will soon be better. Better? I ask. Better. Mabek and the officials have arrived, and they have brought the salaries of the officials and the soldiers. For the holidays. I didn’t tell him that I didn’t see any large bags of money heaved onto our plane. With the government in Juba continually flirting with economic collapse, I wasn’t optimistic that salaries would be paid any time soon.

I arrived back at the celebrations in time for a late lunch, and then, finally, we left: a cavalcade of pick-up trucks kicking up red dust as we cut through town, the dignitaries in the middle of the procession, armed units of the SPLA at the front and back. The sun was falling rapidly from the sky by the time we arrived in Pariang. While the commissioner greeted local luminaries, I walked across the road to the place I was to sleep. It was an old school building, most of it now in ruins, destroyed during the fighting. One central room was still standing, a constellation shining through the holes in the ceiling. I was to stay here with Peter Majong Majak, Unity’s minister of agriculture, and an older man who looked at me distrustfully without fully meeting my gaze, Simon Matuele, the deputy minister of government. Though we had all taken the plane from Juba together, and I had already had lunch with Matuele, he greeted me at the entrance of the school building as a stranger. “You visit us,” he said, “in reduced circumstances.” Matuele’s evident suspicion was combined with a sense of shame that a guest must be shown Pariang in these conditions. There are appropriate times to visit.

Matuele said none of this, as a soldier brought us some water and we washed gratefully, the dust of the journey turning to mud at our feet, before returning to the commissioner’s compound for dinner. We sat under the cuei tree as dusk dusted the compound, and dined on aseeda, while Matuele proceeded to conduct a good-natured investigation. “Maybe, Joshua, you are here because you are angry at Scotland? Do you want to punish South Sudan as an example for all states thinking about secession?” There is laughter around the table, and Matuele, sensing an audience, continued. “My father,” Matuele said, “knew the last British district commissioner. He told me that the British were scared of only two things: the angry German and the naked Dinka. But I am not naked. Are you scared?” More laughter.

The group of women who cooked dinner cleared away the plates as quietly as they had served them, and the commissioner and the journalists announced that they were going to bed. Tomorrow, after all, was Christmas Eve. Majak, Matuele, and myself were left in the darkness, smoking cigarettes and drinking bittersweet tea. It was then that Matuele began the real interrogation.

“Joshua, why are you here? There is no good food. No good water.”

He held up a cup of the tanned water we had been drinking, though it was pitch black, and I saw nothing.

“There is no electricity. No this. No that. Why are you here? You are CIA!”

I laughed, but I was slightly flustered by this, more insistent, hostile line of questioning, and I answered as honestly as I could.

“I want to understand.”

Matuele found this rather pompous answer hysterical and collapsed into laughter. “To understand!” He gestures to an invisible audience. “He wants to understand!”

What do you say when people ask you this question?

I could have given the simple answer I give most people. I am a researcher with a Swiss organization, contracted to write a report on the conflict in Unity state. Matuele knew that already. Why am I here? The easiest answer is that I’m paid, but that truth hides a lie. Some people do come to South Sudan to make money. However, as you know, the organization I was working for doesn’t pay much, and I take these contracts to have an excuse to come to South Sudan. I don’t come to South Sudan for the contracts. I come because I want to understand what is going on, and because, in some dimly felt sense, I hope that in understanding the situation here, and my place in it, I might find some measure of freedom. Perhaps, I hope, in understanding, and in reflecting on what I am doing, and how I am bound up in this country, I might be able to create a space outside of the traps in which I find the international community enmeshed.

Other internationals have more convincing answers. The evangelical interventionists who work for the Enough Project believe their publications can change the situation in South Sudan for the better; they appeal to the American government as if it were an angel of history, ready to rush in and save the world. I can’t believe that. South Sudan’s fate is largely in South Sudanese hands, the actions of the international community are both generally baleful, and unlikely to be changed for the better by my writing. On occasion, to be sure, the state department or the UN takes up something I have written, but their reasons for doing so are internal, determined by institutional priorities in which I have no say. They use my work to achieve purposes foreign to me.

I have friends, war photographers, who come to South Sudan for the purity of their art—in search of the beautiful, the notable, or the historic—or else for the vicarious pleasure of being in a war zone. Some come because it is their job to come. These friends belong to a closely related species, but they are different to us. We come back to this country, year after year, decade after decade. For many war photographers, Congo and South Sudan are essentially similar. For us, they are entirely different propositions.

Why do I come here? It’s too late to ask that question, I want to say. I’ve already been coming here. I’m in it now, up to my neck. It’s too late to turn away. What I want to understand is what I am doing, and that means understanding where I am.

For Matuele, my answer was ridiculous. Knowledge for knowledge’s sake is not a meaningful posture in a warzone. Understanding requires an end. Matuele knows, better than I, that there is no knowledge that is not bound up with a will to know, even if his reductions are too simplistic. Not all knowledge is a question of state power, not all researchers are with the CIA, and the instrumentality of knowledge is not as obvious an equation as Matuele might think.

Still, his laughter haunted me as we walked back to the school, and I lay there, the air hot and still, listening to Matuele snore. What was I doing there? Why did I feel so happy, so fulfilled, that night in Pariang town?

*

The next morning, I awoke early and bounded out of bed in search of a unicorn. Before anyone else had stirred, I was sitting in Monyluang’s compound, writing up my notes and enjoying the sun’s first blush. Finally, around 10 am, the administration of Pariang gathered to eat breakfast. Mabek was staying at another compound. I asked Monyluang about the car. “Yes, Joshua, of course, but after the holidays. You cannot work on Christmas Eve!”

We sat around drinking tea and chatting until the sun was almost at its apex, and I resigned myself to spending the day exploring town. With the two journalists, I set off for Pariang market. The streets were quiet, almost entirely without people, and I felt as if I were walking through the business district of a city on the weekend. Finally, we found some people in the market: a group of young men, idling by stalls that had not been set up, who entertained our questions about life in Pariang.

The year before, the fighting had begun on 17 December, as tensions over the SPLA’s killing of Nuer civilians in Juba led to clashes at the oil fields. A few days later, the fighting moved to Pariang town. Most of the SPLA’s 4th Division, which is based in Unity state, was Nuer, and sided with the nascent rebellion. Up and down the state, SPLA units split. In Pariang town, the rebellious soldiers fought against both those Dinka elements of the 4th Division that remained loyal to the government and local Panaru Dinka. It was never in question which side the Dinka would take. Unity is a Nuer-majority state, and for much of the second civil war, Nuer militia forces headed by the feared general Paulino Matiep dominated the territory, and fought against the SPLA, while terrorizing Dinka civilians. Pariang is one of only two Dinka-majority counties in the state, along with Abiemnom, and remained in the hands of the SPLA-loyalist Mabek Lang throughout the last civil war.

When the current civil war started, the young men explained, the Panaru Dinka felt trapped. They feared that if the whole state joined the opposition, the Nuer would attack Pariang, a small Dinka-majority island, perched precariously at the tip of the north of the state, with no easy means of getting reinforcements. Last December, every young Panaru Dinka man felt he was part of a conflict whose equation was posed in existential terms. The young men I met in the market were among those who fought the rebels last year. The previous Christmas, the air was full of bullets. The rebels moved through this market, helping themselves to some free gifts. They targeted the stalls of Darfuri traders because, the young men said, they didn’t want to pillage the stalls of relatives (Nuer and Dinka frequently inter-marry) or friends, and the Darfuris were perfect strangers, largely unlinked to pastoralist networks of marriage and kin.

The young men looked proud as they explained how well the Panaru Dinka had acquitted themselves. By Boxing Day, the rebels had abandoned their attack on Pariang town and moved south, towards the bulwark of the rebel forces in Bentiu. No one, however, could be sure that the rebels were really moving south and wouldn’t suddenly return to sack the town. Every young man bristled with anticipation and no one else dared leave their tukuls. The streets were empty, and, the young men said, it felt like Pariang had been abandoned.

This image of an abandoned town stayed with me as I said goodbye to the young men and walked aimlessly through Pariang, in search of signs of existence. Christmas had emptied the streets. War and ritual both create moments outside of time, in which we sit in the suspension of the everyday, hiding or resting, unable or unwilling to enter, once again, into the daily life of a place, as if we were on a stage set, and had not yet arrived at the appointed hour for the performance.

Finally, towards the outskirts of town, we found an old woman serving the sweet black tea that fuels my days in South Sudan. I sat in the shade of an abandoned building with the two journalists, Afandy and Francis, and whiled away a few hours drinking tea by the side of the road. Both were Shilluk, one of the ethnic groups that lay claim to the title of being South Sudan’s third largest, after the Dinka and the Nuer. They grew up in Khartoum, displaced by the second civil war, and came of age in the Sudanese capital. Neither came to South Sudan until after independence. Afandy, a broad, tall man whose hands move frenetically, creating worlds as he talks, told me that he didn’t speak Shilluk, and didn’t want to learn. “I am a human, and I am Sudanese,” he said. He was a pan-Africanist, urbane and cosmopolitan. “Why,” Afandy asked rhetorically, “are we fighting tribally? Why divide ourselves?” He felt ambivalent about South Sudan’s secession, and struggled to find his place in a country increasingly divided on ethnic lines.

We sat together and talked about politics. I felt at home with these two men, with whom I could speak almost without monitoring myself. If I had to choose a side in this conflict, it would be the side of Afandy and Francis. They, of course, had no side. Both men lived in Juba and worked as journalists. After independence, Francis had moved to Malakal, the capital of Upper Nile, where his family was from. He told me he got a good job, working for the local radio station. He had a girlfriend, owned property, and could speak Shilluk. Unlike Afandy, who had stayed in Juba, he had felt optimistic about the new South Sudan.

The previous December, as Malakal became the center of clashes within the SPLA, and Nuer forces rampaged through the town, Francis had hidden in a church compound. His residence was burned down. He didn’t know what had happened to his family or girlfriend. He left on foot. “I’ll never forget those days,” he said, “wandering in the swamps, not knowing if we would live or die.” After Francis got to Juba, he had to begin life all over again. Our conversation slowed as Francis talked, the silence eventually encompassing the story, and we sat quietly, drinking tea, as the sun began slowly falling towards the horizon.

At dusk, we watched as the streets suddenly sprang to life. From seemingly deserted buildings erupted processions of young people, holding flags and singing, as if this were a mixture of a Scout jamboree and a carnival. From the edges of the town, groups from the surrounding villages moved in, all of Christianity’s multiple variations finding a place amid the banners and the dancers. As the worshippers converged on Pariang’s churches, we discussed which we should attend for the Christmas Eve festivities. The town’s administration had divided themselves up between the churches, so none should feel offended, but as Francis was a devout Catholic, we decided to join Monyluang at the largest celebration.

The church was dark and empty. This would be a Christmas held outdoors, in the intense heat of the dry season. In front of the church, wooden benches had been set up under awnings made of tarpaulin, candlelight flickering in the impromptu eves. We were some of the last to find space; people already filled the benches, while more streamed in from town and the surrounding villages: in one family, a particularly energetic child clasped a miniature Christmas tree fixedly between eager palms. Old women, wrapped in scarves, with the bright eyes of the devout, sat clasping rosaries. I suspected they had been there much of the day. Inexplicably sitting next to them, there was a man wearing a fluorescent yellow Dar Petroleum jump suit and a pair of work goggles, as if he had just arrived from the oil fields.

Then many of the groups of young men and women that we had seen parading into town put on a display in front of a central fire, and the singing and dancing lasted for hours. Have you ever seen Dinka dancing? The young men leap high into the air, and then swerve mid-leap, their bodies turning abruptly as they dive down, their hands cutting the air, as if spearfishing, or vanquishing an enemy, while the young women behind them sway, and then take their turn, in a dance both athletic and religious. The performance was at once one of combat, seduction, and religious praise, and I marveled at how these different registers combined as we gave thanks for the birth of Jesus.

Towards midnight, the service concluded, and groups of young people started to drift away, holding their banners and singing snatches of song. Francis and I walked towards the commissioner’s compound, cautiously finding our footing in the darkness. On our right, incandescent in the darkness, was a brightly lit stall. Its generator was running but the roar of the motor merely functioned as a growling bass for the highly pitched Dinka rap that was playing out into the night air from someone’s phone. Four young men swayed and laughed, continuing to dance. This, I supposed, was the after-party.

After we passed the group, we descended into darkness again, and I used my headlamp to show the way, wary of potholes. Suddenly, stars exploded through the sky, an angry yellow streaked with red, and we heard the crack of automatic firearms. Francis immediately ducked and ran into a ditch by the side of the road, pulling me with him, as the world erupted in small arms fire. After a moment, amid the crackle of the small arms fire, I could hear laughter. The soldiers were celebrating a Christmas without warfare by firing into the air.

Francis, slightly abashed, dusted himself off and returned to the road. I could see he was trembling slightly; the memory of a Christmas past still lived bright within him. Back at the compound, our ditch escapade had already been reported to the administration and Matuele enjoyed giving me a hard time. “Did you think the rebels had come, Joshua? Or just the naked Dinka? Were you scared?”

Monyluang was less amused. The soldiers were wasting ammunition and would be disciplined. We should not be giving presents to the enemy.

*

The day after Christmas I walked into Monyluang’s compound, early in the morning, and saw a unicorn. It was an improbably new pickup truck. I had to find fuel for the vehicle, but I was free to use it, just as I had been promised. Guor, myself, Afandy, and Francis piled in, along with our driver, a very young soldier whose feet barely touched the pedals, but who proved adept at handling the pot-marked road as we raced to see Nelson Chol, the 4th Division commander who was to organize our trip to the oil fields.

As we drove into the barracks—a collection of tukuls, boots hanging from trees, soldiers washing, or else lounging around—I saw a parade ground at the back of the compound, and on it a man, topless, lying face down, his hands tied to a spike driven into the ground, his back a labyrinth of welts. Guor and the journalists wandered around the barracks, while I entered a tukul where Nelson Chol sat gingerly on a plastic chair, his enormous frame constantly threatening its sagging blue legs. I made our request and he walked outside, issuing instructions into his satellite phone, before entering the tukul once again. I cautiously asked him about the man tied to a stake in the parade ground. Chol smiled and told me that the man was beaten for wasting ammunition the night before by shooting into the air. He assured me that the SPLA, despite the reports of some journalists and researchers… He paused, looking at me. The SPLA is a disciplined army. There is no wasting of ammunition here. I felt trapped, certain that the soldier was being beaten as part of a spectacle that I was meant to witness, so that I could inform the world that the South Sudanese army is indeed disciplined. Plaintively, I appealed to Chol, and told him that I was already convinced of the army’s discipline, and no such treatment was necessary on my account.

Back in the pickup, now accompanied by three soldiers in the back of the truck, and one squeezed between us in front, we pulled out of the barracks and headed west. Guor could read the unease on my face and asked me what was wrong. I told him circumspectly about my encounter with Chol and Guor laughed. “That man is not being beaten for firing in the air, Joshua. He is not even a soldier.” Apparently, Guor told me, soldiers had come and taken—requisitioned—the man’s property, and he had had the temerity to come to the barracks and question the soldiers’ actions. “Chol only told you that to try and impress you,” Guor assured me, laughing.

*

After our meeting with Achuil near the oil fields, we collect even more soldiers, so now our merry group consists of two journalists, the driver, Guor, five soldiers, and myself. As we continue west, towards the Tor oil field, the landscape superimposes itself on my memories of being here in 2012. Nothing seems to have changed. The lil is still a browned green, and cattle can still be seen. It is as if the war had not touched this part of Pariang. On that trip, though, I was with a good friend, a Nuer. I ask Guor whether there are still Nuer left in Pariang county. He smiles and shakes his head. “They would be killed the moment they entered,” he says. The rebels’ movement south last December effectively left Pariang as a mono-ethnic territory. While cross-border travel and trade continues with Sudan, inside South Sudan the war has produced new lines and new, more absolute delineations between people.

It takes us another half an hour to reach the oil platform, which resembles a giant children’s playground. There are metal pipes shining out of the earth, as inviting as slides. Long staircases perch next to huge cylindrical oil tanks, now empty. Containers dot the perimeter of the site, their walls green after the last rainy season, their floors a patchwork of half-burned documents, the carbonized remnants of life in the oil industry. I flick through paperwork in Arabic, Chinese, and English: production figures, requests for leave and the records of workers’ complaints about the late payment of salaries.

The soldiers are as curious about the site as I am. The sticky black residue on the red earth belongs to a world that stretches north, following the pipelines, to Port Sudan, and onward to a global commodity market. It was manned by Chinese engineers who fled the conflict along good roads, constructed by the oil companies, to the oil production sites in Sudan, at Heglig. From the paperwork I can see that while the oil field was operative, the Chinese oil workers often came here during the day and returned to Sudan at night. While the production of oil and the distribution of its revenues didn’t touch these young soldiers, its economic logic crossed national boundaries.

The soldiers responsible for guarding this site are one mile to the north. As we drive up, the small company assembles under a tree. They look bored and grateful for the company. We talk, tell jokes, and I ask them about life. The Tor field has been peaceful since January 2014. Oil production was turned off in a hurry, the soldiers say, and the oil has seeped into the ground. The commander gestures for one of the soldiers to come forward, and he does so shyly, before proffering his arm like a gift: swollen, red, and engorged. It is impossible to know whether this is the result of oil, but I have seen enough of it lying on the surface of the earth to think it might have entered the water table, as it certainly has elsewhere in South Sudan. “There is no good water,” they tell me, showing me a cup of muddy water, drops of oily residue on the surface, “and no medical assistance.”

Everyone looks tired and emaciated. The soldiers await the end of the rainy season, and the hunger it brings. Normally, the rains bring with them two harvests, but the war has disrupted the agricultural cycle, and since June, the soldiers have been without pay, surviving on pumpkin leaves. When they learn we came from Juba, you can see the question burning behind their lips: did we bring their salaries? Before anything else, in the northernmost part of Unity state, Juba means money. For Juba, though, these areas of Pariang are important only insofar as they help a war waged for control of the capital.

The way Juba often seems to see the rest of the country isn’t that different to the view from Luanda: troops are arranged as on a Risk board, with commanders in full control of their forces issuing directives in a war game, as if the fate of South Sudan depended on the actions of just a few men, 21st century Napoleons, and that life was simply a matter of their intentions, unconstrained by the world around them.

So much of the war in South Sudan, though, is slow and boring, and nothing to do with intention. It is war as a duration, not a narrative, into which everyday life slips ambiguously. The troops guarding the Tor field all want to return to the surrounding villages to plant. The line between civilian and soldier here is thin. These young men plant pumpkins and drink bad water, guarding an oil field whose global coordinates remain a mystery, while they dream of heading home to farm, and of a salary and ammunition, delivered from a distant Juba. Their war is the one I want to understand.

*

The next morning, I again bound out of bed, and go to the commissioner’s compound, which looks just as it did the previous morning, with one exception. The pickup truck. When Monyluang finally wakes for breakfast, I ask him when the pickup will arrive. He tells me that it has been requisitioned by the SPLA: they are sending troops to the east of Pariang again, to secure the area, so that maybe people can return to their fields. “But my petrol!” I exclaim, having filled the tank up in anticipation of a week of travel. Monyluang smiles, and there is low laughter around the breakfast table. “Think of it, Joshua, as your contribution to the war effort.”

I laugh, and head to Pariang town, in search of a vehicle to rent—not an easy proposition in a town where the army owns almost all the pickups and petrol prices are stratospheric. As Guor and I pass the gate, I come across Matuele, all smiles, wandering in to have breakfast. “So, Joshua,” he asks me, “have you understood yet?”

Warmly,

Joshua