A Great Piece of Turf (1503) by Albrecht Dürer: before I saw this painting, grassy areas just looked like cluttered, messy greenness. It wasn’t until this picture pointed me towards the variety hidden in the weeds that I began to notice it–or, actually, to rediscover it, since I certainly paid close attention to the weeds when I was a kid.

Here is some of that variety–pineapple weed, dandelion, broadleaf plantain, clover, daisy fleabane, bull thistle, and many others I don’t recognize–all from the same three feet square in front of my house. Each photograph allows one character to stand forth and take the stage, but there is something missing. They don’t express the feeling of peering into a tangled patch of weeds the way Dürer’s painting does. They don’t capture what Dürer’s painting invites me to see.

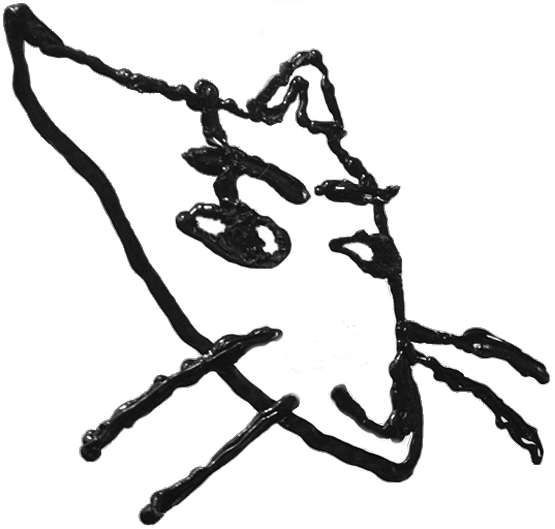

There is a certain kind of attention we offer to works of art. We need to be invited to turn that kind of attention on other sights. The object above is a tool for evoking this attention. It’s called a Claude Glass; 18th century tourists brought them on trips to picturesque places. Turning their backs to the scenery, they would hold up the dark mirror and view the scene’s reflection in it. The effect was to even out the hues of the scenery, making more subdued and painterly. By suppressing something of the real scene’s vibrancy and contrast, the tourists were enabled to view it as a work of art.

Drawing from life is the best tool I know of for evoking attention. A photograph is taken in an instant, but a drawing is an amalgam of many moments of close observation. Using my pencil to follow the slump and curve of these dry leaves and branches required me to attend to them more closely than I could by just looking. In the process, I became aware of just how much I had to leave out. A three-dimensional object cannot live on a page; drawing is a process of painstakingly selecting which details to suppress. It is this suppression that makes the image more legible than the object.

This painting is undeniably cluttered. It’s an explosion of details. Yet the suppression is there: the dragonfly landing on the tulip is nothing but a series of glints, the faintest suggestion of an outline disappearing into the shadow, and pools of darkness threaten to swallow up the stems and leaves.

No matter how realistic an image seems, something is being omitted.

Artists sometimes use grids to break up the scene they’re depicting. Making the object less legible–chunks of color, simple curves within a square–helps to render it legibly.

To recreate something with depth and texture on a flat plane, you have to take it apart with your eyes and reassemble it with your hands; destroy the object to create the image.

The artist who made this platter, Bernard Palissy, cast his ceramics from life, using critters that he caught in the ponds around his house–meaning he had to kill his subjects, literally, in order to represent them. I find his work enthrallingly ugly. The art I like best is messy, profuse, overflowing with detail. A work of art like this has a different relationship with detail. Nothing is suppressed; there is so much complexity that the eye gets lost; looking at it demands a different kind of attention.

But there is another strain of art in which the substrate provides the impetus for the image–as in this painting on marble, in which the variegation of the stone have provided the suggestion of the cloud filled with cherubim.

The subtle variegation in the stone suggests a scene; the artist follows it–like finding shapes in clouds.

There is a point at which the virtuosity of the artist defeats itself, and the detail becomes so overwhelming that it collapses into clutter; to me, looking at this carving by the master boxwood miniaturist Ottaviano Janella just feels like looking at a clump of weeds, without Dürer’s hand guiding my eye.

These are the eyeglasses Janella used when carving his miniatures. Wearing these, he could whittle wood to such a thinness that it would flutter like a leaf when you breathed on it. Maybe if I could wear his spectacles and examine his carving as closely as he did, my breath would everything tremble and the clutter would resolve itself into fine legible details.

Then again, attention itself magnifies. This is another boxwood carving, a prayer bead about the size of a ping-pong ball.

But when you stare at the scene inside, it feels like you could fall into it.

Janella’s box makes me think of this reliquary shrine. The enamel glows, the gold robes hang in elegant folds, but the source of the reliquary’s power are the two boxes of illegible clutter, the relics themselves.