A pastry chef from the fourth highest ranked restaurant in the world prepared a gray canapé infused with Sichuan peppercorn and adorned with freeze dried raspberries. As he did so he imagined his canapés appearing in pictures which would help to drive business to the temporary rooftop dining space his boss had established during the pandemic. He wrote to his followers, “it feels good to be working with my hands again,” along with a photograph of flour spread on his home kitchen table. It had been several months since he had baked in his restaurant kitchen, and all the energy he had stored up from staying at home would release itself in bouts of anger and depression so that, at night, when he couldn’t sleep, he would loudly curse in the bathroom, and repeatedly try to finish a memoir called “Barrio Culinario: Cooking in the Back Alleys of Mexico City.”

His only comfort was his regular contact with a team of four pastry chefs who communicated via Zoom twice a week, and now, at last, met in person to plan out a four-course dessert special. On the final Zoom before their planning meeting, the chef suggested that they include at least one coronavirus-themed dish, and he shared a photograph of the little canapés he had produced the night before. They were made to look like the virus, a gray sphere dotted with red many pronged extensions, represented by freeze dried raspberries. His team applauded the little canapé, laughing and asking how it would taste. “This is gonna be a big hit,” said one.

They set to work the next day stirring together the cream, mixing it with ash, for color, and infusing vanilla, cardamom, and peppercorn into the sweet mixture, which was then set to harden in half-sphere molds. The chef purchased freeze dried raspberries instead of preparing them in the restaurant kitchen’s freeze drying machine, to which he no longer had access. “C’est la vie” he said, smiling as he looked at the inferior freeze dried raspberries that had been prepared in a factory.

The tables were arranged six feet apart to accommodate diners who worked in the financial, insurance, and real estate (or FIRE) professions. Aloe plants with unusual shapes were placed around the rooftop area, having been selected by a design consultant from a nearby office, who was also anxious to work again. She had lavished significant attention on the dried petals of several blooming cacti, scattering them in haphazard rings around the potted plants. The effect was to produce an atmosphere of deliberate ease, a kind of easiness one appreciated all the more for having been so painstakingly created. The canapés had been finished the night before and now had a slight sheen on them; the small dots of light caught the chef’s eye and he had a short “transcendental” experience, as he later explained it to his wife, because of the light reflection, and because he hadn’t worked in such a long time.

The first three nights open went very well. A reviewer from the city’s business paper described the meal as a “flight of whimsical, earthy, and thoughtful presentations culminating in a very a la mode dessert: peppercorn canapés dotted with freeze dried raspberries representing the coronavirus.” The summer air also made for a somewhat more relaxed kitchen environment, which, exposed to the light chatter, felt remote from the old and higher strung days of meticulous presentations and strictly regimented fourteen course meals.

The chef was glad to see photographs of his desserts on the social media feeds of gray-haired doctors and young gourmands.

Then the next morning, he awoke to find that a picture of his coronavirus canapés had gone viral within the Chicago “foodisphere.” The photographer, a doctor at Northwestern Hospital, had captioned it “Tongue-in-cheek-in-mask #coronavirus Thank you for making art that we love to experience and eat (at a safe distance), Chef.” In reply to this word of thanks, many hundreds of people the chef did not know instructed him to stop producing the desserts, telling him he ought to be “extremely ashamed” of himself for having made them. The original photograph had been reposted by a local food blogger who wrote beneath it, “Unbelievable. This isn’t ok… this isn’t ‘cute’. This is shameful. How unbelievably disrespectful to anyone whose life has been lost. I don’t care how you spin it, this is unacceptable.”

The chef thought, “Everything will be taken away from me” as he read through the hundreds upon hundreds of criticisms of his little canapés. He imagined stone-faced sheriffs interrupting a last meal of black beans, in his reduced home, pounding on the doors and removing his children and his wife’s unusual rugs and smashing photographs of the old boats he had taken while traveling in Scotland. They would break into his home and treat his family like immigrants. Then where would they go?

One person wrote that his desserts were “making light of a virus that had claimed the lives of more than one hundred thousand [sic] people” and another, “This is disgustingly disrespectful to make a dessert representing an invasive virus that has killed many souls.” Four wrote that they would not be eating at any of the restaurants within his restaurant group again, and that they would take their anniversaries and birthdays to other establishments. Systematic racism and capitalism were also related via thematic arguments to the creation of the canapés. In their “glib” and “hurtful” stance toward death, the little creams had indirectly endorsed certain decisions furthering the pandemic, even, in a way, contributing to the deaths that weekend of “many underserved people throughout our communities.”

Many of the posters imagined, as they wrote their own criticisms, how the families of persons killed by the little virus would turn to look at them from hospital bedsides, or from the streets where their loved ones had been killed, and offer up a despairing and bereaved expression of gratitude. In fact, many entertained the idea that, though they were doing only one act, they could chalk it up as one of their “small good deeds of the day.”

The chef spoke to his wife about the hundreds of insults his canapés had received. She looked very worried for a moment and asked if he would lose his job. “No, no. I don’t think,” he said. And his boss called, and said not to worry, but that they should stop selling them and “consider a strategy as to how to avoid this going forward.” In deference, the chef agreed to stop making them, and indeed to dismantle the existing canapés by covering them in chocolate and removing the raspberry protrusions. These he ate himself, though he hardly tasted them now.

All the searching critiques ate away at his soul. He started to entertain the idea that there was a hidden callousness deep within him that made him blind and deaf to the suffering of other people. Indeed, he remembered how, once while on vacation in Michigan, he had encountered a homeless man requesting medical assistance, and instead of assisting this person, had instead given him fifteen dollars, all the while worrying that the sun-burnt man with his ragged neck would die that night. However, he also recalled seeing the same man the next day outside of the same ice-cream shop making similar demands of other people.

And this memory emboldened him, so that the fear passed and a sense of affront and upset took its place—in his mind his home was restored, the sheriffs removed their brown hats, setting their eyes to the ground, apologizing, restoring his wife and children on special biers, to their rightful positions in their “nest.” He looked upon the law officers, from his covered porch, with a kind of obvious tolerance all the more painful for having been unearned. The second day, his mind could not be kept on the task of pouring chocolate: he was crafting a lengthy response to all the critics in his post, addressing them all directly in one post, a “bold move,” which after some persuasion his wife supported.

In the meantime, many debates occurred in the comments between people who had or had not lost loved ones, and who were criticizing or defending themselves or the chef. A hidden consensus had emerged among the two sides that, in order to comment intelligibly on the dessert, one ought to have lost a family member to the virus. One man told another poster that, despite the loss of her grandmother, about which he could know nothing, he had also been affected by the virus and that it “was offensive to take offense” at the dessert. She replied that he was “gaslighting” her, and that she had lost both of her grandparents, who had died gasping for air in the ICU unit at Mercy Hospital. In another corner, one man who had claimed to have lost three friends to the virus admitted, privately, that he had only known the three victims distantly, and was not very close to any of them. Then the chef posted his response one night.

He wrote, apropos of his canapés: “Art is often meant to provoke discomfort, conversation, and awareness. This is no different. Everyone on here saying we are somehow oblivious needs to think upwards.” Proceeding to defend his “awareness of the coronavirus” by asserting that he had heard about it “everyday on the radio and tv for several months,” he made his audience to know that he understood that the coronavirus existed and “touched every part of our lives.” He also assured his audience that his canapés were not statements in favor of the current president but rather “manifestations of what we cannot see, reminders to patrons, right as they go, that we are aware that this is still with us and will be for some time.”

In the final paragraph of his response he connected the creation of his canapés with other works of art that had been little understood when they had been first released. He said, “What we often now hail as a gesture that creates awareness—be it during a time of war, famine, or social time—was at its time controversial.”

Immediately many people questioned his application of the term art to his canapés; others questioned whether it would have been better to share an actual discussion of the coronavirus, thereby “using his privilege and influence to broadcast artists of color” who had also been interested in discussing the coronavirus through music, painting, and poetry, and who had thus far received “a fraction of the coverage” that his statement had received. He was directed by one person, whose comment was loved fourteen times, to use the profits from the canapés to furnish the Chicago Freedom School with legal funds. The School faced severe penalties for providing crackers and juice boxes to protestors of police murders. His payment would signal a true commitment to promoting “discussion, politics and art, and enfranchising people who had been silenced by his life decisions,” which included working as a pastry chef and then using his salary to purchase a house, copper pots like those used in French kitchens, and many books about food from around the world. He pondered the challenges now before him in fear and silence and tried to watch again the documentary he had seen, about the painter Gerhard Richter, from which he had derived his philosophy of art.

As he watched the film, the chef’s critic, the original poster, walked around his affluent neighborhood on a pretty, quiet, curving street which terminated at one end in a bookstore and CBD cocktail bar and drug treatment center and on the other, a liquor store in which the last men left from the old neighborhood bought Highife tallboys. He was flying high on the rage and sense of self-importance that his post had given him, and began to imagine, not a career, as that would be too much, but a sustaining side vocation in which he speculated about the callousness embedded in many different restaurant dishes all down Randolph street, where the canapés had been made.

Never in his life had so many people listened to something he said, and the sense of purpose and worth he now felt was qualitatively different from the low-level aggravation all around him and inside him in the advertising firm where he worked. There, for several years now, his ideas had been marginalized, relegated to the pages of medicines and dog treats which yearly required the same glistening clichés without alteration. His comment on the chef’s canapés was different because it was about justice and not about selling meat and pills. He imagined a series of interviews with prominent local reporters about other subtle signals he had discerned in restaurant menus and restaurant decor that indicated that the industry’s bakers and chefs had in some way colluded to disrespect pandemic victims and colonized persons, with whom he stood in solidarity, seeing as he could do this from his relative position of privilege (not easily won, not easily won—his mother had raised him on her own).

All this enlivened and heated his brain, which felt at once constricted, bound inside his skull, and at the same time throbbing, full of a sense of its own strength, to act and to influence. The chef felt much the same.

Long absorbed in the mechanics of his work, the chef had failed until now to consider its revolutionary potential, and how what he did was—whether others understood this or not—animate movements of thought and action in the city; his pastries had perhaps prompted more discussion than Gerhard Richter’s paintings, as interesting as they were, as unusual as they were in their method of conveying feelings to the brain. The spheres and sprays and blocks and triangles which he plated so deliberately in so many different forms—cakes or pies with green tangles of dehydrated fruit, rolls of frozen marrow and gelatinous pearls of almond, saffron, and passion fruit—had occasioned much thought in the world. How many words, how many hours upon hours did they weigh in the minds of local food columnists, and in the throats and stomachs of the elite (though not only them—for sometimes others saved up for years, forgoing other purchases to try his work), and in the thoughts of the city people who knew they would never try them—how many of these shared hours had been concerned with describing, discerning, and digesting his food?

He was walking and thinking, imagining a series of desserts which paid homage not only to significant political figures in the history of Black Chicago (for instance, his son had told him about the muralist Margaret Burroughs), but also to important abstractions. For so much of his life his desserts had been, as it were, non-representational, not even rising to the level of abstract art, which at least showed raw feelings, but simply food, good-looking food, but good-looking in the way that decoration is. What he was on to now was different. This was “dessert as provocation,” he thought, making a note on his phone to remember this phrase. The sudden intrusion of a public into his life—a thinking, rather than eating life—rattled him, sent jolts of juice and verve into his footsteps as he strutted away past the CBD cocktail bar at the end of the pretty, curving street.

He wandered down the street towards where his critic stood, stopped in thought, and, not knowing it was his critic, felt himself immediately drawn to the young man. His critic’s Tom’s shoes spoke of a goodwill that he suspected he shared, and he rose outside of himself, addressing a stranger for the first time in many years, saying, “You look deep in thought!” The critic turned and replied, smiling, “I am! Ha! I am!” and he was glad someone had spoken to him. In the chef’s fervent, “creative”-looking eyes and charitable shoes he sensed an immediate friend.

“What are you thinking about?” asked the Chef.

And the critic answered, “I am thinking about how different my life is these days. Something has changed. I feel full of this energy and a sense the world is going to change.”

“Really?” asked the chef, “I feel that way too.”

“Yeah,” said the critic, “I don’t know how to describe it, I don’t—” and here he paused to look in the chef’s eyes, searching for a sign to go forward with disclosure, “I feel as if I had been trapped within myself, as if my whole life had just been about me, me, me, and now as if there’s something different. I care much more about others, but also more about myself. I realized these two things go hand in hand, caring about others and caring about yourself.”

The chef said, “Yeah, that’s so true. You have to put the mask on yourself, during airplane crashes, and then onto your child.”

“Yeah, right! And I don’t want to toot my own horn, or whatever, but the reason I felt this is because, I—how would I describe it?—I made an intervention.”

“A change?”

“I would say an intervention. I think what I did made an impact, in some small way, not only on them, but on hundreds of people. I realized I have this power.” He paused. Something in the periphery of his vision seemed to move, or at least be capable of movement—it was as if his new powers had set all the solid world around him into a motion, a possible motion. “I learned to use my own voice,” he said, and, rising from reverie, remembered to ask his new friend, “Have you ever felt that way?”

“Yes, yes, it’s just funny you say that, because I couldn’t have described the feeling any better myself. My own ‘intervention’—God, what a word! My own intervention raised a lot of really searching, really beautiful discussion, some of it, not necessarily stuff I agreed with, but it really got people thinking, and in a way that nothing I’ve ever done has before, like it just seemed to motivate people. And you have to understand, I’m, I’m a person whose comfort zone is working in the background of things, like working and contributing to other people’s projects. But this just really brought me out of my shell. It made me realize I might be a different kind of person than I thought I was, more political, but also more artistic, more committed to, what should I call it, like, a conceptual practice?” The chef’s voice signaled in him a newfound confidence, an interest in other souls, a kind of beautiful presence, a wishfulness, a way of being with others, and a mindfulness—all this was enveloped, so he thought, as the lavender scented smoke enveloped his rhubarb gels—with a spirit of action, liveliness, innovation, and engagement.

“A conceptual practice. Wow. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah! I don’t mean this in some romantic way, but I just feel this connection with you, this immediate connection.”

“I feel the same way, like we’re on the same wavelength, and I don’t need to explain anything, I don’t need to justify myself.”

“I don’t need to justify myself, I don’t need to educate you, that’s not my job. We’re just there.”

The two fast friends decided to return to the CBD bar down the street where other, like-minded individuals discussed issues such as police abolition, sourdough bread, racial conflict within the Bon Appetit test kitchen, the ignorance of Southern voters, the price of wine, tattoo artists, driverless cars, and other things that people in their milieu considered interesting and worthy of discussion. Infused in their drinks were herbs grown on rooftop gardens and juices from Latin America, along with CBD oil derived from marijuana plants grown downstate, crystallized sugar, chili flakes, and dried essence of lime.

The men sat at the window at first, but soon the chef, rising in unexpected exaltation, called out to the young owner of the bar, demanding a tour of the small kitchen area. The openness of the pastry chef’s smile so affected the young proprietor that he let the two men into his kitchen, and even put on an entertaining show, featuring blends of ethnic sauces and cocktails, and a reduced sauce from a short and violently burning fire. The men called out “Opa!” like in Greek kitchens, and admired the young barman’s commemorative banana sauce bottles from the Philippines. Each confided happy secrets to his new friend in voices that were open, friendly, poetic, radiant, beautiful and freeing, soon convincing the young bar owner to embrace the same change of perspective they had adopted. On the spot, he decided to dedicate his life to making appetizers that would abstractly impart to diners the legacy of colonial violence in the home country of his great-grandparents, the Philippines, which he had visited twice in week-long stretches.

The friends’ radiant joy even permeated into the music in the bar, which consisted of samba classics from the 1980s selected by an educated intern working for a music streaming service in Sweden. The dance songs imbued the air and CBD-infused spirits and appetizers with an energy at once concrete, nebulous, sacred, revolutionary, and good, as if Logan Square, then Chicago, then the World would turn over a new leaf from the conversation wafting—no beaming, no, too strong, a gentle word is best—rising from this interesting bar. Reporters with nasty and bitter attitudes, whose viewpoints had been modified negatively by their trade, walked into the bar and snickered at the sight of the chef and the critic sitting side by side. However, the friends didn’t hear the reporters—they were busy ascending to the rooftop with multiple cocktails in tow, walking arm in arm and envisioning certain things. The reporters felt estranged from the boundless, humid good faith circulating around the bar; they grimaced at their shoes, all torn up by the pavement, knowing that at last they had been left behind by history, and would not break the good news.

From the top of the bar one could look out to the west, north, and south. There were long rows of low bungalows, two flats, three flats, courtyard apartments and rising glass towers in the city, these last protruding here and there like orchids in a sea of green weeds, or diamonds in the rough, or, what comes to the same thing, red spots on a pirate’s map, places to ransack and raid, or bookmarks in the book of Capital (the bookmarks seem to say, we want to return to here, to put my money on this neighborhood). These areas were not the “domains” of the two fast friends, and not, lest we confuse joy for avarice, even “a blank canvas”—rather they were, they said in unison, a “field of possibilities,” a phrase that poured down into them like rain and made them want to kiss one another in a way that was ecstatic but not romantic. They looked out upon the Logan Square eagle statue, a marker of its Puerto Rican heritage, and upon the rows of shops and theaters to the west, where even now so late into the night young people walked and leaned into one another, intoxicated by the numerous delicious fruit- and CBD-infused cocktails to be had from bars grown up in gutted, renovated homes of families who pounded steel for a living or processed waste. Some of these neighborhood “characters” still wandered the streets, puzzling over the presence of nose rings and men in “lady clothes” and families in hemp shoes, the purchase of which supplied the same to an African child. “Well, I’m glad somebody gets to live in the safe neighborhood,” they said, and many had to admit that the parks were cleaner now and that on Friday nights they didn’t have to stare into blinding lights and the ‘whoop whoop’ of a police siren just for having some rum. They no longer called out “sweetheart” to girls passing by because class differences made them deferential and they didn’t know how rich women would respond to this term; women from the neighborhood who had moved west would still pass through it, on their way to work, and, seeing these men, would pity them, despise them, and say to themselves, “It’s time to move on.”

The two friends were roving around the rooftop, taking in all of these scenes of the night and approving of all of them, loving down on them from the heights. What was especially sacred and unique about their new connection was how little of it had to be communicated, and how much could be understood by speaking of it in general terms. In fact, to fly down to the particularities of their lives would, both men sensed, endanger the experience. And so, as they carried on their talk, drunk and dreaming, both sensed a subtle fear that in revealing the events that had led to their transformations, the night would end, a bright, glaring sun would rise, and they would have to resume their day jobs and lives just as they had been before.

The two new brothers were shouting now, shouting and crying. Neither had checked their phones in some time, and they had missed the new debate emerging in response to their original conflict. Certain questions were raised: what effect could these events have upon the world? How many people would see them? How many would look at them and think to themselves “Having seen this, I have come to understand that coronavirus is not serious?” Relatedly, “How many victims of the virus, how many of their relatives, how many dying people, will have seen them and felt deeply disrespected?” “And here I want to distinguish,” said one learned commenter, making a subtle point, “between people who feel genuinely disrespected, and people who, thinking they are acting for others, make a show of being disrespected on behalf of people who may or may not care about this debate at all.” This comment led some people who had been affected by the virus to insist that they had been offended by the pastries. Many other people had never heard of this pastry and were not affected by it, even by the butterfly effect.

Larger questions arose: how had so many hundreds of people come to attribute such significance to the little pastries, seeing in them unwitting tools in the maintenance of white supremacy, tacit advertisements for the president’s agenda, veils of labor exploitation etc? These questions sat uneasily in the minds of the hundreds upon hundreds of people who had participated in the debate. Many doubled down on their position that their individual efforts in the debate were each “one small good deed” and that when these parts were summed we could collectively realize a world profoundly “other than our own.” “What is this ‘our world’ you speak of?” asked one commenter, “In what sense can we speak of a ‘we,’ an ‘our,’ when I see these pastries as insignificant and you as revolutionary, in a small way?” This was a death knell. The debate had “escalated quickly” they all agreed, too quickly, like an escalator running up to a floor that has not yet been built, which, carrying you up so high above your peers, deposits you at the end right back where you started, fallen and with fractured bones. One could only maintain their position in the heights, like on an escalator, by continuously running downwards.

The woman who had claimed she had lost a relative admitted that it was a distant relative she hardly knew, and the man who had defended the artistry of the pastries with a comparison to Marcel Duchamp admitted that he did not know anything about the artist except that he had once made a urinal. They both forgave themselves, the woman deciding to listen to talk-shows about serial murderers and the man, after discussing his options with other commenters, decided to call up some friends to go to one of the new novelty experiences which entailed recreating the life of an abducted person.

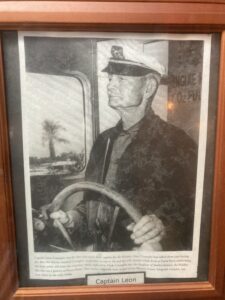

The night was not so young—she was weary, but also restless with her silence disrupted more and more often by the heavy stops of white buses. Still, the news had not yet reached the chef and the critic. They were still looking out to the big flat west. To the few looking up from the street level, they looked like a pair of sea captains, surveying the New World from the bow of a ship. A night-shift security guard, returning to her home as dawn drew in, craned her neck to see the men on her way to the bus stop. She then looked in the direction of where their fingers were pointing and saw the same old city, the place where she was born.